And indeed, it cannot be denied that the most successful practitioners of the art of life, often unknown people by the way, somehow contrive to synchronise the sixty or seventy different times which beat simultaneously in every normal human system so that when eleven strikes, all the rest chime in unison, and the present is neither a violent disruption nor completely forgotten in the past. Of them we can justly say that they live precisely the sixty-eight or seventy-two years allotted them on the tombstone. Of the rest some we know to be dead though they walk among us; some are not yet born though they go through the forms of life; others are hundreds of years old when they call themselves thirty-six. The true length of a person's life, whatever the Dictionary of National Biography may say, is always a matter of dispute.

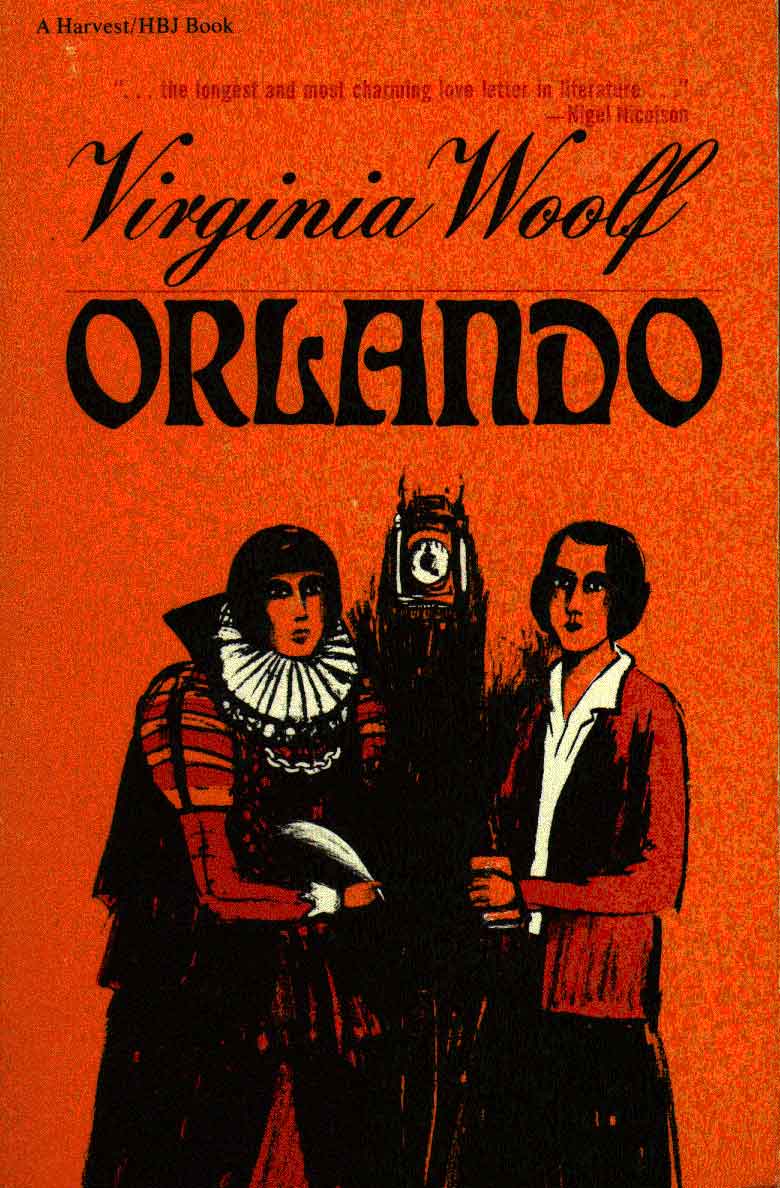

And indeed, it cannot be denied that the most successful practitioners of the art of life, often unknown people by the way, somehow contrive to synchronise the sixty or seventy different times which beat simultaneously in every normal human system so that when eleven strikes, all the rest chime in unison, and the present is neither a violent disruption nor completely forgotten in the past. Of them we can justly say that they live precisely the sixty-eight or seventy-two years allotted them on the tombstone. Of the rest some we know to be dead though they walk among us; some are not yet born though they go through the forms of life; others are hundreds of years old when they call themselves thirty-six. The true length of a person's life, whatever the Dictionary of National Biography may say, is always a matter of dispute.Virginia Woolf's Orlando is a strange book: A sort of love letter to a married woman, in which the woman spends the first half of the book a man. Orlando, the alter ego of Woolf's friend/lover Vita Sackville-West, begins life as a boy serving in the court of Elizabeth I; later, as an ambassador to Constantinople for Charles II he suddenly becomes a she, in a scene that Woolf drags out with laborious humor:

And now again obscurity descends, and would indeed that it were deeper! Would, we almost have it in our hearts to exclaim, that it were so deep that we could see nothing whatever through it s opacity! Would that we might here take the pen and write Finis to our work! Would that we might spare the reader what is to come and say to him in so many words, Orlando died and was buried. But here, alas, Truth, Candour, and Honesty, the austere Gods who keep watch and ward by the inkpot of the biographer, cry No! Putting their silver trumpets to their lips they demand in one blast, Truth! And again they cry Truth! and sounding yet a third time in concert they peal forth, The Truth and nothing but the Truth!

Woolf is quite clearly having her bit of fun, not least from mimicking the silliest floridness of Enlightenment writers, but in the book's general mode, which pretends to be a biography cobbled together from real sources, and in such setpieces as the "Great Frost" that turns Elizabeth's Thames into an endless carnival rink. The circuitous, often inscrutable prose that typifies Woolf's more "serious" fiction is reserved for the book's latter portions, in which Orlando, now a woman, adjusts to the advent of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (the fact that no one thinks it's odd that Orlando is over 400 years old is one of the book's better jokes).

Along the way Orlando falls in love, is rejected, joins a band of gypsies, becomes ambassador, is courted, falls in love again, is reciprocated, and writes a poem--"The Oak Tree," for which the quotations in the text are actual reproductions of a poem by Sackville-West. The point, I suppose, being that Sackville-West's work, as well as person, represents the best of 400+ years of European culture, or, rather, as something that, like the best literature, battles against the expectations of its own age:

Orlando was unaccountably disappointed. She had thought of literature all these years (her seclusion, her rank, her sex must be her excuse) as something wild as the wind, hot as fire, swift as lightning; something errant, incalculable, abrupt, and behold, literature was an elderly gentleman in a grey suit talking about duchesses. The violence of her disillusionment was such that some hook or button fastening the upper part of her dress burst open, and out upon the table fell 'The Oak Tree,' a poem.

But moreso, Orlando learns in his/her 400 years to exist beyond words. She and her husband, Marmaduke Bonthrop Shelmerdine, speak in a "cypher language which they had invented between them so that a whole spiritual state of the utmost complexity might be conveyed in a word or two without the telegraph clerk being any the wiser, and added [to the telegraph] the words 'Rattigan Glumphoboo,' which summed it up precisely." Or, sweetly, they speak not at all:

...and really it would profit little to write down what they said, for they knew each other so well that they could say anything, which is tantamount to saying nothing, or saying such stupid, prosy things as how to cook an omelette, or where to buy the best boots in London, things which have no lustre taken from their setting, yet are positively of amazing beauty within it. For it has come about, by the wise economy of nature, that our modern spirit can almost dispense with language; the commonest expressions do, since no expressions do; hence the most ordinary conversation is often the most poetic, and the most poetic is precisely that which cannot be written down. For which reasons we leave a great blank here, which must be taken to indicate that the space is filled to repletion.

Of course, a great white space follows. There is an overwhelming suggestion, I think, that since no words can really express how Woolf feels about Sackville-West, any words may do, and the silly, absurd, ironic mess that is Orlando is as great a testament as any that could be made. As such, Orlando is a book as much about the limits of what can be said as it is about the limitlessness of one man/woman.