Tuesday, December 30, 2008

Carlton's Favorites from a Year of Reading (2008)

10. The Assault on Reason

I read this during the final weeks of the presidential election. Al Gore went up a few points in my book (that's right, I keep a book in which I rank everyone I know on a scale of one to seven) and Dubya went down a few more.

9. Timothy; or Notes of an Abject Reptile

One of the weirder books that I read this year.

8. The Tale of Despereaux

I am all about anthropomorphic animals.

7. The Napoleon of Notting Hill

Earlier this year, I read a collection of Chesterton's Father Brown stories, and The Man Who Was Thursday was my favorite read of 2007. Chesterton is fast becoming one of my favorite authors. And he's so dreamy.

6. The Golden Compass

I absolutely loved this book and the two that followed it (The Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass). It is sad that the film adaptation was so abysmal.

5. At Large and At Small

A collection of essays

Both enlightening and fun,

I would recommend

This to anyone.

4. The Green Mile

This is only the second book by Stephen King that I have read. I read The Shining a few years ago, and it scared the bajeezes out of me. The Green Mile was not scary, but it sure thrilled the bajeezes out of me. Bottom line: I've got bajeezes that can't wait to be teased out of me.

3. The Idiot

I was nearly halfway through this book before I realized it was not a biography of Pauly Shore.

2. Twilight in Delhi

Ahmed Ali beautifully blurs the line between prose and poetry in this novel set in early 20th century India.

1. Life of Pi

When I put this book down, I knew that it was going to be a hard one to beat. The rest of the books on this list have moved around, and some that were initially a part of the list were dropped, but Life of Pi has always remained in the top spot.

Book Review of Mine with the Weirdest Comments

Assassination Vacation

Sexiest 50 Booker

Christopher Chilton (sorry Brooke, good effort)

My Book Resolution for 2009: More books with bunnies.

Thursday, December 25, 2008

The Napoleon of Notting Hill by G. K. Chesterton

So ends of the Empire of Notting Hill. As it began in blood, so it ended in blood, and all things are always the same.

So ends of the Empire of Notting Hill. As it began in blood, so it ended in blood, and all things are always the same.Chesterton begins The Napoleon of Notting Hill with some remarks on the art of prophecy. He states that there are always people who try to predict what will happen in the future. Their standard practice is to take some facet of the era that they live in and extrapolate it into the future. Chesterton writes, "There were Mr. H. G. Wells and others, who thought that science would take charge of the future; and just as the motor-car was quicker than the coach, so some lovely thing would be quicker than the motor-car, and so on forever." Chesterton does not put much stock in these 20th century soothsayers, saying that people seem dead set on proving the prophets wrong. No matter how much "progress" the world has experienced, people resist change, seemingly determined to repeat history's mistakes. In the last line of this opening section, Chesterton states, "When the curtain goes up on this story, eighty years after the present date, London is almost exactly like what it is now." So after Chesterton spends fifteen pages describing why these prophecies never come true, he turns around and writes his own little prophecy. Chesterton loves a good paradox.

The Napoleon of Notting Hill was published in 1904 and was Chesterton's first novel. While he set his story eighty years in the future, Chesterton's 1984 is not a society in which are held under the thumb of government, rather it is a society in which people simply don't care. As Chesterton puts it, "The people had absolutely lost faith in revolutions." Kings are indiscriminately selected from the populace. They are surrounded by others and wield very little power. However, when Auberon Quinn is selected as the next King of England he starts implementing bizarre rules and regulations that change the face of England. He drafts the Charter of the Cities, which not only respects, but also bolsters the autonomy of each city, returning England to a more romantic time. Auberon creates all sorts of pomp and circumstance to make his days more enjoyable. Indeed, the purpose behind nearly all of these decrees is merely to amuse the king.

Ten years of this "lark" go by and the various provost have grown accustomed to all the strange rituals and customs they have to observe in order to get things accomplished. However, they still find them -- and the king -- absolutely ridiculous. All the provosts, that is, except one: Adam Wayne. A young man who has grown up under this ridiculous rule and has completely bought into it. Chesterton describes him thusly: "Out of the long procession of the silent poets, who have been passing since the beginning of the world, this one man found himself in the midst of an heraldic vision, in which he could act and speak and live lyrically."

There is to be a new road run through Pump Street in Notting Hill. According to the provosts from the communities it was to run through, it would benefit everyone greatly. They are all in support of it, save one. Wayne, armed with the power that the Charter of the Cities gave him, takes a stand against the construction of this new road, stating, "That which is large enough for the rich to covet, is large enough for the poor to defend."

Wayne's rigid stance on the issue of the road leads to the rest of the provosts mustering troops and marching them into Notting Hill to force the rogue provost to comply. But in a hilarious turn of events, Wayne crushes their forces, which are much larger in number and turns them out of Notting Hill. Eventually, Wayne is at war with the rest of England. As the fighting continues, the plot gets more and more abstract -- just as the plot of The Man Who Was Thursday did -- it also gets all the more intriguing and funny.

The Napoleon of Notting Hill ends with a truly epic battle in which much of Notting Hill is destroyed. Although Wayne is right in the thick of the fighting, and his forces are defeated, he somehow manages to survive. The last few pages of the book find him and Auberon, who is still king, trading deep philosophical statement's in the dark. Initially, each man is not sure who he is talking to -- it is not made clear to the reader either -- and it is hinted that each of the men may think they are speaking directly with God. Upon realizing whom he is speaking with, Auberon admits that the Charter of the Cities was simply a lark, that Wayne had devoted his life to a big joke. The king states, "Suppose I am God, and having made things, laugh at them." Wayne responds, "But suppose, standing up straight under the sky, with every power of my being, I thank you for the fools' paradise you have made." The book ends with these two men walking off together into the night, one man laughing at the world that surrounds him, the other adoring it.

As with the other works of Chesterton that I have read, this relatively short book packs a mean philosophical/literary "one two" punch. There are many things that I took away from this book, but the two main points as I see them are: a single strong-willed person can have a profound -- and often unexpected -- effect on the world around him; and that while people are prone to repeat the same mistakes that they have made all throughout history they are simply trying to live in a world that they had no part in creating.

Monday, December 15, 2008

Doom: Knee Deep in the Dead by Dafydd ab Hugh and Brad Linaweaver

If you think this video would make a good novel, you should definitely read Doom: Knee Deep in the Dead.

Saturday, December 13, 2008

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

Of course, it isn't just Diaz that predetermines Oscar's demise, but fuku, a Dominican curse that follows Oscar's family over several generations, all the way back to the monstrous reign of Rafael Trujillo, whose specter hangs over the book even long after the de Leons have moved to America. For Oscar's mother and grandfather, fuku meant savage beatings and imprisonment at the hands of the Trujillate. For Oscar, fuku means that he is cursed to play Dungeons and Dragons while the cool kids are at parties; it means while he's catching up on his anime everyone else is getting laid--a lesser fuku, you would have to admit, though perhaps not by the degree you would suppose. Oscar lives a life that, while marginal, is uniquely American; Diaz shows us how cultural ideas can translate strangely across nations and generations, yet remain unmistakably relevant. Though he is wheedled by his family and friends for being un-Dominican, it isn't until he returns to the Dominican Republic, compelled by possibly requited love, that the fuku can be broken.

And as compelling as Oscar's story is, The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao can be a frustrating read because too often Diaz lets everyone else get in the way. The middle section of the book is cored out to accommodate lengthy discourses on his sister, his mother, and his grandfather, and while those stories are interesting in their own right, leaving Oscar to the endpapers of his own book seems somehow unjust. I found myself thinking of two other books which deal with the same cultural collisions with less mess: One is The Joy Luck Club, which packages each character's story into neatly stacked chapters. The other is another Pulitzer prize winner, Middlesex, which, while by no means a great success, at least has the sense to build a family story chronologically to create some sort of narrative thrust.

But Oscar Wao, coño, what a mess. It reminds me of one of those plastic novelty slugs filled with water--you know, the ones that fold over themselves like an elongated donut so that you can't hold onto them*. And this one's sprung a leak. There is an underlying pattern, I'm sure, that Diaz had in mind by heading backward in time with each successive chapter only to rocket back to the beginning, but the result is maddening. I kept expect to return to Oscar, who is the book's only truly interesting character, but instead I kept getting rewarded by another trip in the Delorean (and here's where Yunior, Oscar's roommate and narrator, would have provided a much more obsure example of a time machine to color the narrative).

On the micro level, too, Oscar Wao is unwieldy--Diaz writes in a unique twist on that hyperactive, barely stable post-modern dialect that is peppered with oblique sci-fi references, unnecessary Spanish, lengthy footnotes, and muddled metaphors. It's hard not to admire its breathtaking energy, but it's the kind of style that works only once and I fear it will inspire a thousand would-be imitators. Behold:

And who knows what might happen to the girl among the yanquis? In her mind the U.S. was nothing more and nothing less than a pais overrun by gangsters, putas, and no-accounts. Its cities swarmed with machines and industry, as thick with sinverguenceria as Santo Domingo was with heat, a cuco shod in iron, exhaling fumes, with the glittering promise of coin deep in the cold lightless shaft of its eyes.

Yanquis and pais I find forgivable, but why subject us to the teetering construction that is sinverguenceria instead of "shamelessness?" And then there's cuco, which as far as I can tell suggests "cuckoo" but more likely refers to a mythical bogeyman-like monster, this one "shod in iron" like a robot. And notice how that last sentence, as evocative as it is, lacks a subject or lets one--"its cities swarmed with machines and industry"--be lost in the shuffle. "The glittering promise of coin deep in the cold lightless shaft of its eyes" is a jumble of half-metaphors. This isn't a sentence; it's a heap of jargon. I'm not even going to mention the lack of quotation marks in dialogue.

I wanted to like this book, but it is elusive. It's as if too often Diaz wants us to love this book for its manic nature, its quirkiness and affability, but it is difficult to love Oscar and his book simultaneously. Oscar himself is slow-moving, ponderous, and deep; his Brief and Wondrous Life is, regrettably, none of those things.

*There has to be an official term for these. I don't know what they're called so I can't find a picture of one.

Pet Sematary by Stephen King

Sometimes dead is better.

Sometimes dead is better.Severe Spoilers.

I'd say I'm a fan of Stephen King. I've read 23 of his books, including On Writing and Danse Macabre, his only non-fiction as far as I know. Of the books I've read, I think I've enjoyed almost all of them, although King has a tendency (especially nowdays) to stretch a 30 page story into a 300 page one. I said that to say this, though: I've never been scared by one of King's books or short stories until I read Pet Sematary.

The plot is very simple, which is probably why it's so effective: Louis Creed to the town of Ludlow with his wife Rachael, his son Gage, and their pet cat, Winston Churchill. Soon after arriving, Winston Churchill is struck by a truck and killed, and Louis' old neighbor, Jud Crandall, tells Louis a secret. Behind their house, there's a cemetery. Animals buried in it come back to life. Louis buries Winston who does indeed come back, but something isn't quite right. One day while playing, Gage is hit by a truck and killed. You can connect the dots here.

The real horror of Pet Sematary doesn't really come from the plot, which is as old as the art of scary stories themselves. Be careful what you wish for. Don't tamper with cemeteries. Sometimes dead is better. It's the atmosphere, which is considerable and completely unrelenting, and in the realistic depiction of the Creed family as they struggle to deal with the death of their son. The book's climax, the resurrection of Gage, is both its centerpiece and, somehow, beside the point. Next to the horror of seeing your baby son run down, what's a zombie or two?

Pet Sematary is completely unmerciful. It never cuts its characters or its readers a break. Something about it is fundamentally disturbing in a way most of King's work (and most horror in general) isn't. It's nihilistic and hopeless, and that's why it works.

The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon

Having no apparatus except gut fear and female cunning to examine this formless magic, to understand how it works, how to measure its field strength, count its lines of force, she may fall back on superstition, or take up a useful hobby like embroidery, or go mad, or marry a disc jockey. If the tower is everywhere and the knight of deliverance no proof against its magic, what else?

Having no apparatus except gut fear and female cunning to examine this formless magic, to understand how it works, how to measure its field strength, count its lines of force, she may fall back on superstition, or take up a useful hobby like embroidery, or go mad, or marry a disc jockey. If the tower is everywhere and the knight of deliverance no proof against its magic, what else?

The Crying of Lot 49 was confusing. I don't say that as a pejorative, but a simple statement of fact. Although it's Pynchon Lite from what I hear (certainly lighter than the 800pp Gravity's Rainbow), it's still an exercise in maximalism and absurdity, full of inside jokes, historical references, and weird names.

The plot, as far as I can interpret it is this: Oedipa Maas, happily married post-modern woman, stumbles across a worldwide conspiracy that may or may not involve the government and every person she has ever known (including her disc jockey boyfriend). Actually, the conspiracy may not even exist. It centers around an auction (The auctioning of Lot 49) and a symbol resembling a trumpet. Also, the postal service and a play that is written out in play format about halfway through the book.

I'm sure Crying is a very good book if you study it. It was entertaining and fairly amusing even when I didn't. Still, the lack of resolution and the distance created between the reader and the characters reminded me of the first third of Cosmopolis, and my uninformed opinion about Crying is similar: It's a good book, maybe even very good, for those who are drawn in enough to draw out the references on top of references on top of everything else. The writing is strong, the story is interesting, and I didn't care for it a whole lot.

Candide by Voltaire

Truly, this is the best of all possible worlds.

Truly, this is the best of all possible worlds.Spoilers.

The subject matter of Candide is among the most timeless in all literature. Why is there evil in the world? If there is a loving creator, why does he allow bad things to happen to us? If we are completely in control of our own fates, why hasn't society weeded out the dross?

Candide is a naive young man living in a peaceful kingdom. He is preparing to marry the girl of his dreams. He is cheerily oblivious to anything negative in the world, indoctrinated into the beliefs of his mentor Dr. Pangloss, beliefs that can be summarized by my lead-in quote, “Truly, this is the best of all possible worlds.”

Candide's commitment to this philosophy is tested when his kingdom is attacked. His family is violently murdered, his fiancée brutally raped and disfigured, and his mentor, Dr. Pangloss, is killed. Candide himself is sold into slavery, and things only get worse from there. His fortunes improve only in preparation for further degradation. He attempts to cling to his belief in the best of all possible worlds, but gradually grows more and more disenchanted, finally rejecting it. Oh, and somehow this book manages to be pretty funny.

The interesting thing about Candide is Voltaire doesn't actually try to directly answer any of the questions raised in it. Instead, he satirizes the blind optimism and gullibility of his countrymen, particularly the religion ones whose beliefs mirrored those of Pangloss. Candide is often presented as pure cynicism, but Voltaire's point doesn't seem to be that the world is a relentlessly terrible place as much as it is that each man makes his own way and controls his own circumstances. This is essentially the conclusion Candide himself arrives at, finally finding happiness when he decides that, both literally and metaphorically, “every man must tend his own garden.” Rather than a wholesale attack on religion and optimism, I read Candide as a call for a realistic, pro-active approach to life, where we actively make it better rather than assuming it will naturally take the best course.

Oh, and seriously, it's pretty funny.

Marley and Me by Josh Grogan

"A person can learn a lot from a dog, even a loopy one like ours. Marley taught me about living each day with an unbridled exuberance and joy, about seizing the moment and following your heart. He taught me to appreciate the simple thing--a walk in the wood, a fresh snowfall, a nap in a shaft of winter sunlight. And as he grew old and achy, he taugh me about optimism in the face of adversity. Mostly, he taught me about friendship and selflessness and, above all else, unwavering loyalty."

While this may not be the best way to judge character, I feel that men that love dogs are generally trustworthy. After all, any good dog owner has to value simple companionship and have a lot of patience. When I met Jamie (the significant other) at the beach and we started talking about our favorite books, he cited Marley and Me as one of his. I had not heard of the book and assumed it was about Bob Marley (who the dog in the book is named after). His correcting me on the subject matter led into a story about the love of his life--a boxer named Tyson. This is when I decided that Jamie was probably a pretty good guy. After we got back from the beach, Jamie gifted me the book that we had talked about as a going away present when I headed back to Boone for school.

Grogan, who is a journalist by profession, writes in a way that I can see appealing to a broad audience, both book lovers and the book shy alike. I feel like 300 pages about man and his best friend would be too much for anyone, however, regardless of the quality of writing. That's exactly what made Marley and Me an appealing read... it wasn't just about Marley, though he certainly played an important role. The book is about a dog, but it's also about forming a new family, miscarriage, postpartum depression, the love between Grogan and his wife, and what happens when crime becomes personal. Of course, there are plenty of light hearted moments that the book touches on as well--the day Grogan decided to move his family across the country on a whim so that he could see what following a dream felt like, how children from Florida react to their first snow, and the day Grogan became a stage dad for Marley on the movie set of The Last Home Run. When Jamie told me that the book would make me laugh and it would make me cry, I told him he was full of it. In the end, he was right. I bawled.

The novel is suppose to be about "life and love with the world's worst dog." I don't know that Marley is the world's worst, but I don't know if I'd want him for a pet, regardless of all of his more endearing qualities. Marley flunked out of obedience school (as did my dog Jazz, more or less, but I was 9 when I took her so that might be a factor). He had a cage that he managed to work his way out of that was so impregnable looking that Grogan named it Alcatraz. Marley clawed and bit his way through hundreds of dollars worth of drywall not once but every time it stormed. You get the picture.

This book took me all semester to read. It wasn't that I didn't enjoy it, because clearly, I did. Grogan just didn't pull me in quite enough to make me work him into my schedule as often as I made time for my required class reading, I guess. My time with Marley was squeezed in between classes and before work meetings more than it was enjoyed in lengthy sittings.

While I haven't seen the movie based on the book as it hasn't been released yet, I do have to say that whoever did the casting made very different decisions than I would have (not that anybody asked me). Jennifer Aniston and Owen Wilson are nowhere near the Josh and Lisa that live in my head.

The Tenth Justice by Brad Meltzer

The last crime-related novel that I read that I will admit to liking is The Rainmaker by John Grisham. As you can tell by my reading list from this year I'm not exactly a literature snob (as most of my books are embarrassing) but I loathe the formulaic writing that the crime genre is known for and therefore stay away from it when possible. My Criminal Procedures professor (whose name is also Chilton) decided that for our class he would have us read a fictional novel about the Supreme Court and then write a paper on it to see if we could catch what was and was not accurate about the Court inside of Meltzer's work. Fair enough, I guess.

The Tenth Justice's protagonist, Ben Addison, is bright and ambitious, making his way straight out of Yale into the position of a Supreme Court clerk for the fictional Justice Hollis. When Ben starts out, Hollis is in Norway vacationing for the last month of summer. On his second day there, a big death penalty appeal lands in his and Lisa (his co-clerks lap) and in the middle of their scurrying to figure out the perfect solution, a man calls claiming to be an old clerk of Hollis' named Rick offering his welcome and extending the opportunity to give advice. After helping Ben with the appeal, Ben falls into trusting Rick and incidentally slips him the outcome of a huge merger case weeks before the decision becomes public, which leads to a stock scandal. When Ben realizes that Rick has pulled a fast one on him, a wild goose chase begins for Rick, who has disappeared with the exception of occasional threats delivered to Ben, Lisa, and Ben's roommates, who have all managed to get involved and put themselves on the line for Ben in trying to help him. Eventually, Rick returns, trying to bribe Ben into becoming his partner and giving him the results of another decision involving rezoning expensive historical property. There's a lot of violence and carrying on while Meltzer drags his feet trying to figure out how to close the novel, where eventually the good guy wins but not without a slap on the wrist for breaking the Court Code of Ethics, of course.

The only likable character in the book is one of Ben's roommates, a goof off named Ober that doesn't belong at his job at the Senator's office at all and is constantly scheming up business ventures such as starting the first non-Jewish deli which he would name Christ! That's a Good Sandwich. In the middle of all the ridiculous wire tapping and lie detector test taking that fills up this book, Ober decides he's a failure and hangs himself. This did not make me happy. Without his antics and laughable suggestions for solving Ben's problems the rest of the book was irredeemable.

I read the book while working a football security shift for the school on Halloween and between an angry girl dressed as a cowgirl getting in my face and having drunk locals (read: scary rednecks) try to sneak into the building it kept me entertained enough, I guess.

The Realm of Possibility by David Levithan

"Here's what I know about the realm of possibility-/it is always expanding, it is never what you think/it is. Everything around us was once deemed/impossible. From the airplane overhead to/the phones in our pocket to the choir girl/putting her arm around the metal head./As har as it is for us to see sometimes, we all exist/within the realm of possibility. Most of the limits/are of our own world's devising. And yet/every day we each do so many things/that were once impossible to us."

There seems to be a recent outbreak of YA fiction novels being written entirely in poetry, because like the Sones book I reviewed not too long ago, there isn't any prose to be found here, either. Levithan has created twenty different complex and believable high school students with interconnected story lines who each offer us up just one poem to summarize their situation. What I think was the most interesting about the way that the book was put together was the success with which Levithan carefully crafted the poems so that the style of each would match the fictional author's voice and personality. It's easy enough to create different characters, sure, but to each give them a different style of writing without any overlaps is another story all together. It goes without saying that in some of these poems work better than others.

My favorite of all the poems involved one of the squares (involved in Honor Club, Quiz Bowl, etc.) buying marijuana for her mother who was undergoing chemotherapy and then watching her mother laugh for the first time in ages and turn the music up so that she could get out of bed to dance. The poem continues on to the next day where the dealer offers her more pot and she declines saying she can't afford it and he insists she take it anyway, without saying too much letting her know that he knows it isn't for her and what it's for, thus challenging her assumptions about him through his strange show of kindness. One of the more amusing poems was written about how someone felt he was losing his girlfriend to Holden Caulfield, because after reading The Catcher in The Rye about a thousand times she decided that everyone, including him, was a phony that could not be trusted. I think at some point or other every book nerd falls hard for the ideology of one of their favorite authors or fictional characters but I don't know anyone that goes around lecturing others about it. (I'm partial to Atwood girl, myself.)

I wasn't wild over The Realm of Possibility but I think it did a great job of exploring a very diverse group of students--from the choir girl to the goth to the gay couple to the anorexic girl to the school jock that seems to have it all together to the angry goth chick writing things like "YOU ARE IMPLICATED" and "YOU ARE FOOLISH IN YOUR UNHAPPINESS" over lockers and desks throughout the school.

The most frustrating thing about the book is that it isn't organized very well and it's often hard to tell who is speaking due to the structure Levithan employs. It is divided into five different sections and each section has a page that has the names of the characters who are in that section in the order that they appear, but their names are not anywhere to be found on the poems themselves, so I had to keep flipping backwards to figure out what was going on.

Twilight by Stephenie Meyer

When I was middle school all you could get me to read was fantasy and science fiction. After years of a constant intake of vampires, werewolves, aliens, and dragons I was sure I would never want to pick up another book with any of that as content again. As a result, I resisted the recent hype around books like Harry Potter and Eragon. However, even if I'm fantasy-weary I'm still a female and am a sucker for books about relationships as long as that's not all they are about, so I decided to give in to reading Twilight.

Meyer really sucked me in despite my cynicism. There were certain aspects of the book that made me roll my eyes, of course--for example, the book is just littered with long, descriptive examples of Bella gazing endlessly into Edward's eyes and Meyer is a bit heavy handed on working to make Edward seem aloof and mysterious. (Come on, Edward, you may be a vampire but get over yourself.) Despite the fact that their relationship seemed rather obsessive and shallow to me, Meyer did a great job of creating convincing chemistry between the two. I could also appreciate the fact that despite their intense attraction to one another their storyline remained innocent and sex never entered into the picture at all--especially since there are so many young fans. The major objection I had to their relationship that Edward used his abilities to do things that the typical jealous male could not do--like listen to her conversations with other people by reading the mind of whatever male Bella was speaking to and getting into her room to watch her sleep before he ever even had any kind of relationship with Bella. Creepy much?

While her writing style often left a lot to be desired her imagination surely didn't. My favorite part of the novel was a scene where the vampires decided to include Bella in a game of baseball. Through the game Meyer really let them show off their super-human abilities. Because of their heightened strength, they had to wait until a thunderstorm to play because the crack of the ball against one of their swings created a deafening sound that could be mistaken for thunder that would have attracted outside attention if it wasn't for the storm. Also, Meyer created a breed of vampire unlike any other that I've read. I appreciated the fact that she didn't borrow many ideas from the old myths and decided to put her own spin on things.

Despite the fact that the majority of Twilight's 500 pages are dedicated to the young conflicted couple, my favorite character by far was Alice. Alice is endlessly accepting and loving, impish in both appearance and action, and can see the future even though she doesn't remember her human past. I feel like she created a kind of calm for Bella that no one else in the novel could and created a more "human" connection with Bella than even her family or school friends did. I also appreciated the fact that even though she had a heart so big that it seemed to take up her whole body she could still piss Edward off endlessly. Because he often got on my nerves, I got a kick out of someone pushing his buttons for a change.

The last thing that I'll say is that Meyer must have a wonderful sense of humor, because this book made me laugh a lot, which is something that I wouldn't have really expected. Both Edward and Bella were given quite a few good one liners and their comebacks were also pretty witty and sharp.

I did a little bit of poking around Meyer's website and I have to say that for a stay-at-home Mom and a practicing Mormon she defies a lot of stereotypes. I plan on forgetting my fantasy aversion long enough to finish this series and maybe her novel The Host. She let me escape my life for a while and let me enjoy a book without weighing me down and after exams and a rather tough semester, that's exactly the kind of reading I'm up for.

The Meaning of Consuelo by Judith Ortiz Cofer

Friday, December 12, 2008

Phantoms by Dean Koontz

Phantoms is a promising concept ruined by lackluster execution.

Phantoms is a promising concept ruined by lackluster execution.Jenny Paige returns to her hometown of Snowfield, Colorado to find it deserted. Going house to house, they discover a few bodies dead or badly mutilated. Eventually an older police officer whose mannerisms sounds suspiciously like Columbo, is alerted and arrives in the town with a few of his men one of whom is very rude and perverted and guess who gets turned into a monster first and has his head eaten off by a giant fly you're right.

Phantoms creates a creepy atmosphere up front (much like another book I recently reviewed), but can barely sustain it past the first 100 pages. When the creature begins revealing itself in the form of grotesque bugs and the bodies of those who've been killed, it's a little eerie. When it happens for the 600th time, it's grating.

In regards to the creatures orgins, the book flirts with a lot of the same ideas as Stephen King's Desperation, but doesn't have the guts to follow through with them. It's suggested that the creature is Satan himself, and that the book is somehow a metaphor for the world... but actually, the monster is some creature who was born from the primodial soup but never really left it behind. Evil Gak, you might say.

Anyway, this book wasn't very good, but it was better than The Homing, so I give it a 3/10. As far as promising concepts? I'm a sucker for creepy towns.

The Life of Pi by Yann Martel

I have a story that will make you believe in God.

To choose doubt as a philosophy of life is akin to choosing immobility as a means of transportation.

The Life of Pi is narrated by young Piscine (“Pi”) Patel. His family flees India and its unstable politics, and heads for Canada, taking with them all the animals from their zoo. En route, a storm hits their bot and it sinks, leaving only Pi, a hyena, a zebra, an orangutan, and a huge Bengal tiger afloat on a lifeboat.

The first third of the story covers the time before Pi's family leaves, and introduces us to his interest in world religions. Although raised as a Hindu, he meets with both a Muslim Cleric and a Catholic priest and finds value in those religions as well. When confronted about the contradictions of subscribing to the three widely variant faiths, he replies, simply, “I just want to love God.”

The second third of the story covers the shipwreck and the time following, during which Pi's adventures read like some modernized version of the Odyssey, complete with his own monsters and cursed islands. These episodes are entertaining, and sometimes quite touching, but the book's real payoff (and literary aspect) comes in the last section, when Pi is rescued. He tells his story to the men, the same story that we have been reading ourselves, but his questioners do not believe him, and press him to tell them what really happened. While claiming that his original story accurately reflected events, he bows to their questioning and tells them another, far darker but more believable story and asks them to choose the one they prefer.

That, I guess, is the central question of the book, which story to choose. Rather than making the reader believe in God, The Life of Pi seeks to give a framework under which belief is reasonable. Pi's fantastical explanations of the events (if one chooses believe the second story is the more literal truth) serve as a method for him to cope with the awful things that have happened. In the same way stories about tigers and living islands allow him to look objectively at subjects like the deaths of his parents, God and religion provide a way to look at life's most elemental tragedies—mortality, illness, sadness—and see more than a series of random happenings. Whether or not such a story will really make you believe in God probably depends on how much you can buy into such an amorphous, inconcrete version of a higher power, but it's still food for thought.

The Bonfire of the Vanities by Tom Wolfe

Sherman McCoy is a self-styled Master of the Universe. Along with his fellow stockbrokers, he is key to the success of one of New York City's biggest brokerages in the late 1980's. He is rich, but up to his neck in debt, married to a beautiful woman but concerned that she's aging, and in love with a job that hangs on the whims of the world. One night, out with his mistress Maria, a wrong turn into the projects leads to a hit-and-run, and a young black man is killed.

When Reverend Bacon (the book's stand-in for Al Sharpton) launches a public crusade against the man responsible for the hit-and-run, Sherman finds himself blacklisted. Everyone wants to bring him down, including a mayor desperately looking for a way to reconnect with his minority populace, Peter Fallow, a washed-up reporter looking for a story to revive his career, and Larry Kramer, a district attorney who desperately wants to sleep with a mysterious brown-eyed juror.

Wolfe is a proponent of the school of New Journalism, and Bonfire, heavily researched, combines a ripped-from-the-80s-headlines story with a strong eye for satirizing the excesses of that era. Sherman, initially a loathsome, self-absorbed bastard, becomes almost sympathetic as the story unfolds, revealing him as a hopelessly naive, insecure status-seeker. Others, like DA Larry Kramer, begin more sympathetically but no one comes out looking all that good in the end.

Wolfe's writing style is interesting and sometimes irritating (mostly due to his overuse of ellipsis), but it keeps the action moving and molds the characters from one-dimensional archetypes into three-dimensional people. When Sherman finally reaches the end of the line (written as a front page story for the New York Times) it is shocking but seems inevitable. The characters do more less what you would expect with the hands the story hands them, but that's not a negative. There are no breakout moments, no sudden bursts of character or long soliloquies about the injustice of it all. Just a solid, believable story that's well worth reading.

The Bhagavad Gita by Krishna

I read the Bhagavad Gita because it was short and because it seemed like it would be interesting. It's one of the primary religious texts of the Hindu religion, but you wouldn't necessarily pick that up from the cursory read I gave it.

It's set up in the format of an epic poem, with the narrative picking up right before Arjuna, our protagonist, enters a battle in a civil war, fighting against his own people and even some of his own family. While he's debating the best course of action, the god Krishna comes down and has a little chat about life, philosophy, and everything to set his mind at ease.

It touches on some of the cardinal concepts behind Hinduism as I understand it, including reincarnation and the godliness of all things. It also talks about aspects I'd never considered, such as when Krishna explains why there's nothing wrong with killing your enemies. Something to do with everyone ending up in the same place anyway. Makes sense to me.

To be honest, I enjoyed the Tao Te Ching more, but I understand that there is more than one key text to Hindi, and also that this is only part of a much larger poem. Perhaps it's more interesting in that context. Without it or any religious affiliation, it didn't really grab me.

Edit: Thanks Brian in the comments section for pointing me to this free online translation. The introductory notes are particularly helpful.

Thursday, December 11, 2008

Kraven's Last Hunt by J. M. DeMattis

Spyder, spyder burning bright!

In the forests of the night

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

As far as I know, I'm the only comic book reader on the blog. By comic book, I mean monthlies normally featuring superheroes like Spider-Man and Batman, not graphic novels like Watchmen or that weird Japanese thing Nathan read last year. Owning around a thousand comic books (and having read most of them) I realize that the medium tends toward adolescent wish-fulfillment rather than substance, but occasionally a storyline, even one featuring an established character like Spider-Man, will provide a little food for thought.

The story is set up thusly: Kraven the Hunter, the world's greatest, uh, hunter, is old and near death. He ruminates on his life and realizes he cannot die happily until he conquers the one beast which has so far eluded him: Spider-Man, of course. Taking Spider-Man by surprise during on of his nightly patrols, Kraven shoots him with some sort of hallucinogen, throws a net over him, and, while Spidey is struggling to escape, shoots him with a rifle and buries his body. Kraven then steals the Spider-Man costume an goes on a quest to prove that not only can he defeat Spider-Man, he can defeat the only villain to best Spidey (at least recently), a half-human, half-animal creature named, naturally, Vermin. Kraven finds Vermin and captures him.

Of course, Spider-Man isn't actually dead. He's in a comatose state induced by whatever he was shot with, and he awakens (and crawls dramatically from his grave) to find that two weeks have passed, during which Kraven has been impersonating Spider-Man, albeit a much more violent version. Spider-Man, still in his weakened state, tracks down Kraven who refuses to fight him, instead releasing Vermin for a rematch. Spider-Man incapacitates Vermin, and Kraven, always a bloodthirsty hunter of his word, says his unting days are over now that he's defeated Spider-Man. Spidey leaves to deliver his captive to the police, and, while he's gone, Kraven blows his head off with a shotgun, leaving a note absolving Spider-Man of all crimes committed during Kraven's time beneath the mask.

When I was reading comics more regularly, I knew that J. M. DeMattis' work tended to delve deeper than most mainstream comic scribes'. The comics he helmed tended toward a lot of metaphysical navel-gazing that sometimes worked (as in most of his Spider-Man run) and sometimes didn't (Dr. Fate). Kraven's Last Hunt is DeMattis at his best. He draws Kraven, normally a silly, shallow villain, as a sad disturbed man who sees Spider-Man much as Ahab saw Moby-Dick, as an embodiment of everything wrong with the world. To him, Peter Parker represents the forces that brought down his homeland, Russia, and killed his mother. In contrast to Spider-Man, who distances himself from the evil fights both by refusing to kill and by making light of even the most dire situation, Kraven's response to his demons is to become one with them, to try and embody, understand, and destroy them. Kraven becomes, temporarily, Spider-Man, but Spider-Man never allows himself to become Kraven, always standing just across the threshold from his animalistic instincts. Kraven's madness is ended when he sees Spider-Man post-resurrection and realizes that he is, after all, only a man, and a good one at that, one that fights against the same forces that Kraven abhors. Ultimately, however, it makes no difference—Kraven's fate is sealed as soon as he defeats Spider-Man. Without the thrill of the hunt, the natural predator has no reason to live.

Taming the Beast by Emily Maguire

"He said that I had proved to him that resistance was pointless. He said that there was nothing left to protect us from each other anymore. We've crossed the line.'"

I had heard too much about this book--both good and bad--not to pick it up at Barnes and Noble when I saw it, especially after it had been dubbed the new Lolita. The title, of course, is a nod to Shakespeare and his reference to sex as being the beast with two backs. Literary allusions are an important part of the novel, as our young and twisted protagonist Sarah is seduced by her 38-year-old English teacher who baits her with the likes of Donne, Carew, and Dante. Not long after their violent and terrifying affair starts, Mr. Carr's wife finds out about it and gives him an ultimatum that takes him far away from Sarah so that his reputation as a teacher, man of God, husband, and father is not shattered by knowledge of his pedophilia. Before he leaves Sarah, however, he takes her out and attacks her so violently and for so long that when he drops her back off at her house she's nearly half dead.

After being abandoned my Carr at 14, a long cycle of promiscuity and recklessness starts for Sarah that leads to things she had never seen coming--such as being raped by two of the few people she said no to and being both emotionally and physically scarred for life in the process. The incident becomes the talk of her town in Australia and her parents more or less force her out of her house before she's even finished throughout high school, leaving her to fend for herself and pay both rent and college tuition with a seedy waitressing job and occasional prostitution. Throughout the novel, her relatively normal best friend Jamie tries to save her--offering her the possibility of a normal relationship until he accidentally impregnates his girlfriend leading him down the aisle and away from Sarah. After her support system has been completely and utterly altered, Carr appears again. With his return, Sarah moves in, cuts ties with everyone she knows, drops out of university halfway through her senior year, and loses her job. Her days are spent in his apartment, memorizing entire books of Ted Hugh's poetry because he demands it, taking breaks only to call him about fifty times a day. She stops eating until eventually she looks like the young girl that she was when Carr found her. Sarah's life is taken over entirely by the man that had destroyed it eight years before.

While I do think this book has several important things to say and has a great deal of literary worth it was difficult to read. Some of the passages were nauseating and cringe-inducing in ways that I had never come across in reading before, mostly due to Sarah's lack of self respect which as a fellow female I find hard to tolerate. Obviously, the scenes between Carr and Sarah were also uncomfortable. The only remotely likable character in the novel was Jamie, who was still capable of doing terrible things. After being Sarah's sole confidant and friend, when she goes to him for help after nearly kiling Carr for trying to leave her to resume a normal life, Jamie is so tired of her and her constant cycle of self destructive behavior and immediate cries for help that like everyone else, he too victimizes her. In the end, it's ultimately Jamie that dies because upon realizing what he has done, he has a heart attack leaving the wife he was desperate to leave for Sarah a widow.

Basically, I still don't know what I think about this book and it's a bit too disturbing to think about any more than I already have.

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

I Am the Cheese by Robert Cormier

I Am the Cheese may be the best thriller I've read in years. Whether this is a strong compliment because it's officially a YA novel, or faint praise because I don't read many thrillers, I'm not sure. Regardless, IATC gripped me from the second chapter and I finished it just a couple hours later.

The story, already summarized nicely by Chris and Carlton, follows the events surrounding Adam, a young man whose family is an inductee into the witness protection program. The narrative of the book is split, with about half consisting of transcripts of taped interviews and half chronicling Adam's bicycle journey from his home to Rutterberg, Vermont to see his father in the hospital. Things are not as they seem, however, and the final section of the book (along with a couple pages of government paperwork to clarify) turns everything on its head. For a YA book, the ending is somewhat ambiguous. At first glance, it appears that Adam's journey has been entirely fabricated in his mind, probably to deal with the trauma of losing his parents, but Cormier leaves open a couple other possibilities as well. It is possible that Adam is reliving something that actually happened at one time, and it seems equally possible that Adam is just mental and none of the book's events happened at all. It's never made explicit, and somehow that makes the last chapter even more chilling.

After reading The Chocolate War and I Am the Cheese, I'm impressed with Cormier's books. I'm planning to read a couple more of them, although I'm curious if they all hold to the nihilistic worldview presented in the books I've read. I'll touch more on the specifics in my review of The Chocolate War.

Also, I'm pretty sure this is the worst cover this book has ever had.

Saturday, December 6, 2008

I Am the Cheese by Robert Cormier

I cannot remember ever being this impressed with a kid's book. Well, maybe Peter and Wendy. But certainly nothing from modern juvenile fiction has struck me as much as I Am the Cheese. In fact, it impressed me so much that I thought for a moment, "Oh shit--can my kids really read this?"

I cannot remember ever being this impressed with a kid's book. Well, maybe Peter and Wendy. But certainly nothing from modern juvenile fiction has struck me as much as I Am the Cheese. In fact, it impressed me so much that I thought for a moment, "Oh shit--can my kids really read this?"Well, they kind of have to because I told them to buy it, so. Anyway, as Carlton describes, I Am the Cheese is the story of Adam Farmer, who is trying to ride his bike from Monument, Massachusetts to Rutterburg, Vermont, to see his father. The narrative is interspersed with moments in which Adam is being interviewed by a psychologist, in which it is revealed that his family was in the Witness Protection Program and his real name is Paul Delmonte. And then, as you're trying to piece it together, Cormier slips the whole rug out from underneath you, with a pretty deft "it was all a dream/mental illusion/the Matrix" switcharoo.

How is it handled? Well, let me tell you this--I had to read the end a couple times to understand it. My seventh graders might read it once. Cormier smartly makes the bike ride narrative as simple as possible, letting readers (especially young readers) reserve their mental faculties for figuring out the interview sections, but at the end his straightforwardness gets muddled a little bit. And that's a shame, because this is a doozy of a book--full of pathos, with strong characters and a real ear for the thoughts and speech of children.

But try telling a thirteen-year old about pathos.

BONUS: SUPER-CREEPY COVER PICTURE!

The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan

Here it is, in the twilight of the year, and not only am I getting destroyed by Carlton, I am getting passed by Brent, and it looks as if fifty is a near impossibility. Even the books I read I pretty much read for work--case in point, this novel, The Joy Luck Club, which I am about to read with my tenth graders (and so had to quickly read myself).

Here it is, in the twilight of the year, and not only am I getting destroyed by Carlton, I am getting passed by Brent, and it looks as if fifty is a near impossibility. Even the books I read I pretty much read for work--case in point, this novel, The Joy Luck Club, which I am about to read with my tenth graders (and so had to quickly read myself).I had gotten the impression somewhere that Amy Tan was a lightweight, and that The Joy Luck Club was a pretty Hallmarkish simp-fest about mothers and daughters rediscovering their relationship. I am please to report that while it does fall firmly in the stylistic arena of most pop-fiction, Tan's dissection of how families interact across cultural boundaries is pretty compelling.

The Joy Luck Club is split into 16 stories, many originally considered as separate stories not meant to tell a single narrative. There are four mothers who escaped China during the Sino-Japanese War of the 1940's and their four daughters who grew up in San Francisco's Chinatown. The one is exception is Jing-Mei Woo, who, just as she has replaced her mother in the womens' mah jongg circle--the titular club--tells four stories, assuming her mother's pair.

In Chinese, "joy luck" is one word, and its English equivalent not quite up to the task of translating it completely. In the same way, Tan explores the way that certain Chinese concepts fail to make the translation in the lives of their daughters, and the frustration of both sides who essentially live in separate cultures. To one of the daughters, it may seem that feng shui is an outmoded concept with no practical meaning, but she fails to see that the way her hastily constructed table falls apart is indicative of the weakness and fragility of her household and her marriage.

I am having trouble remembering specific episodes; for the most part, these characters are interchangeable. They are all, you get the impression, Amy Tan an Amy Tan's mother, and so there is very little cross-pollination between the stories. For the most part, each story tells about one pair of mothers and daughters, and the other characters appear only incidentally. As a result, The Joy Luck Club cannot cohere an struggles as a narrative. But the stories themselves are carefully contained and affective; I hope that this makes it easier to read for my kids.

Monday, December 1, 2008

The Giver by Lois Lowry

Jonas trudged to the bench beside the storehouse and sat down, overwhelmed with feelings of loss. His childhood, his friendship, he carefree sense of security -- all of these things seemed to be slipping away. With his new, heightened feelings, he was overwhelmed with sadness at the way the other had laughed and shouted, playing at war. Be he knew that they could not understand why, without the memories. He felt such love for Asher and Fiona. But they could not feel it back, without the memories. And he could not give them those. Jonas knew with certainty that he could change nothing.

Jonas trudged to the bench beside the storehouse and sat down, overwhelmed with feelings of loss. His childhood, his friendship, he carefree sense of security -- all of these things seemed to be slipping away. With his new, heightened feelings, he was overwhelmed with sadness at the way the other had laughed and shouted, playing at war. Be he knew that they could not understand why, without the memories. He felt such love for Asher and Fiona. But they could not feel it back, without the memories. And he could not give them those. Jonas knew with certainty that he could change nothing.Chris just reviewed this book a couple of weeks ago. I would mention that while I don't disagree with his description of this book as essentially 1984 for tweens, The Giver actually put me in mind of A Brave New World. Chris does a good job summing up the book. I agree with his assessment. I too wish I had read this book when I was in the 5th or 6th grade, because I think it would have had a profound effect on me. This is yet another in a long line of books that unfortunately landed on the chopping block at the Christian school I went to.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera

Einmal ist keinmal. What happens but once, says the German adage, might as well not have happend at all. If we only have one life to live, we might as well not have lived at all.

Einmal ist keinmal. What happens but once, says the German adage, might as well not have happend at all. If we only have one life to live, we might as well not have lived at all. I started my review of Lolita by saying that I was really unqualified to talk about the book in any sort of meaningful way. It was dense, complex, often over my head, and completely enjoyable. I feel roughly the same way about The Unbearable Lightness of Being. The difference being that I didn't like it nearly as much as I liked Lolita. And in my way of thinking, the books do share some similarities. Both could be described as a novel of ideas. Both of their stories have a dreamlike quality to them. And both of the books deal with sex. Sex was the underlying theme of Lolita, however, it was Humbert Humbert's lust that was on display, not his acts of sex. But in Lightness, sex is front and center and standing at attention. While the book itself is about something much bigger, sex is the driving force behind much of the storyline.

The novel is set in Prague in the 1960s, around the time of the invasion by the USSR. Tomas is a highly successful Czechoslovakian surgeon who looses his job for not towing the line of the Communist Party. His wife Tereza is a politically active photographer. There are two secondary characters, Tomas's mistress Sabina and Sabina's married lover Franz. The story revolves around the intertwined lives of these four people.

I have been thinking about how to describe this book for a while now, and the best I can do is that it is a like a licentious fairytale. But while the inherent moral of most fairytales is that love conquers all, the moral of Lightness is that life is ephemeral. Take this passage in which Franz is trying to figure out if he should leave his wife for his mistress: "Human life occurs only once, and the reason we cannot determine which of our decisions are good and which bad is that in a given situation we can only make one decision; we are not granted a second, third, or fourth life in which to compare various decisions." If each of us only has only one life to live, then does not that life take on a certain degree of lightness? Kundera's characters have little epiphanic bursts throughout the novel where they seem to grasp -- or at least grasp at -- at this concept. It is when they are most happy, most content with there life. And why not? By its very nature this concept is not burdensome, but liberatingly light.

Sunday, November 30, 2008

The Pleasure of my Company by Steve Martin

This book had the same pros and voice as Martin's first book, but I was about halfway through it before I really got into it. That surprised me since I was completely focused from the first sentence of "Shopgirl". In the end, Daniel Cambridge won me over though. At first I thought he was retarded and I thought the way he rationalized his own actions would look completely crazy to anyone looking on. He even recognizes that what he does might seem crazy to people who don't understand the reasoning.

This book had the same pros and voice as Martin's first book, but I was about halfway through it before I really got into it. That surprised me since I was completely focused from the first sentence of "Shopgirl". In the end, Daniel Cambridge won me over though. At first I thought he was retarded and I thought the way he rationalized his own actions would look completely crazy to anyone looking on. He even recognizes that what he does might seem crazy to people who don't understand the reasoning.I think the story is basically one of an obsessive compulsive trying to find someone to love. I like that, because I've thought a lot about the idea of perspective, and how everyone's actions are reasonable from their own perspective and how when I am looking at someone and evaluating them, they are taking in information about me at the same time. I think the best thing about Steve Martin's writing is that he gives every persons perspective rationally, and treats it like any person would treat their own thoughts and ideas.

Shopgirl by Steve Martin

"When you work in the glove department at Neiman's, you are selling things that nobody buys anymore."

"When you work in the glove department at Neiman's, you are selling things that nobody buys anymore." I adored this book. It was simple, but a really accurate way of telling about life without embellishing anything, and still keeping it interesting. The characters aren't particularly compelling, but I loved them because they were so normal. Their screw-ups are just a part of the world they live in and not a tragic make or break to hang the story on. I also really liked that the story accepts that it is ordinary, and skips to the pertinent parts that need to be told instead of trudging through each day whether that day added to the story or not. I like they way Martin looks at Mirabelle, and says, this is what she is doing, this is what she is thinking, and this is what she is feeling, without ever judging her actions or motives.

Friday, November 28, 2008

The Homing by Jeffrey Campbell

I couldn't find a thing about this book anywhere online, and I can't find my copy of the book to get the author's name off of (edit: found it). Even this cover image is my rough Photoshopped approximation of the cover. I guess that means The Homing is either a lost classic or a piece of junk better off forgotten.

I couldn't find a thing about this book anywhere online, and I can't find my copy of the book to get the author's name off of (edit: found it). Even this cover image is my rough Photoshopped approximation of the cover. I guess that means The Homing is either a lost classic or a piece of junk better off forgotten.I bought this book (at Goodwill, .69) for two reasons. 1) The premise, a small town in upstate New York being taken over by a malevolent hospital, sounded interesting in a pulpy, cheap kind of way. 2) The name of the town is Chilton. An inside joke for the loyal 50Bers.

So, a retired cop, Darryl, visits his estranged daughter, Claire, in Chilton. They are estranged because she left college and a promising career as a doctor to marry a man (Phil), and move to Chilton to be his loyal housewife. Ever since the move, Claire hasn't seemed quite like herself. Darryl's first night in Claire and Phil's house is one of the only genuinely creepy bits in the whole novel, but it does manage to create an atmosphere where nothing is overtly wrong but nothing is quite right either.

Unfortunately, the book can't quite decide what it wants to be, so it jumps from atmospheric pulp to weak-sauce thriller to weird old-people romance to government conspiracy and back again over and over and over. By the time it ends (with Darryl being brainwashed into a permanent citizen of Chilton, for those interested), it's kind of numbing and really dull.

Also, the hospital mentioned in the back of the book? Two, three pages, max. I don't even remember what it was for. I would say making the fake cover was more fun than the book.

Thursday, November 27, 2008

The One Percent Doctrine by Ron Suskind

If the Western world was really going to make a pretense of a higher moral departure point — of greater sympathy and understanding for the human being as God made him, as expressed not only in himself but in the things he had wrought and cared about — then it had to learn to fight its wars morally as well as militarily, or not fight them at all; for moral principles were a part of its strength. Shorn of this strength, it was no longer itself; its victories were not real victories; and the best it would accomplish in the long run would be to pull down the temple over its own head.

If the Western world was really going to make a pretense of a higher moral departure point — of greater sympathy and understanding for the human being as God made him, as expressed not only in himself but in the things he had wrought and cared about — then it had to learn to fight its wars morally as well as militarily, or not fight them at all; for moral principles were a part of its strength. Shorn of this strength, it was no longer itself; its victories were not real victories; and the best it would accomplish in the long run would be to pull down the temple over its own head.-- George Kennan looking out over war-torn Germany after World War II

Pulitzer Prize winner Ron Suskind trains his sharp, analytical eyes on the War on Terror. His previous book, The Price of Loyalty, focus on the early years and of the Bush administration, revealing that the overthrow of Saddam Hussein was in the works long before the World Trade Center attacks. The One Percent Doctrine picks up roughly where Loyalty left off. It is the rest of the story, as Paul Harvey would say.

The "One Percent Doctrine" is often referred to as the "Cheney Doctrine" since he was the one to articulate it, and ensure that those in the administration as well as those in government agencies adhered to it. It its core, the doctrine is this: When assessing terrorist threats, if there is a one percent chance that the intel is correct, then the US acts as if the evidence is rock solid. Leave no stone unturned. It seems fairly easy to see the the problems that an approach such as this would cause. But after the 9/11 attacks, Cheney and the president held action in high regard. They didn't prize thinkers, people who could see that international issues are multifaceted. They wanted to surround themselves with doers, people who acted on instincts and suppositions, never mind that they weren't always right. Cheney's "One Percent Doctrine" was the framework under which these actions took place., and it fundamentally informs the way the US is fighting the War on Terror.

I am not going to attempt to get into the details of this book -- too much is covered. But I will say that this is not simply an attack on the Bush administration. It is a critique of US intelligence and of the way that our nation is waging this global war on terror. Suskind spoke with a host of government officials at the state and federal level -- some from the White House. The conclusion that he draws is that in its no-holds-barred pursuit of its enemies, the US has killed thousands of innocent people, alienated many of our allies, trampled the civil liberties of its citizens, and astonishingly caught very few terrorists.

Suskind ends the book by citing a text foundational to both Christianity and Islam. Deuteronomy 16:20: Justice, justice shalt thou follow, that thou mayest live, and inherit the land which the LORD thy God giveth thee. He states that most Hebrew scholars agree that the word "justice" is not simply repeated for emphasis, but that it is said once for the ends and once for the means.

Thursday, November 13, 2008

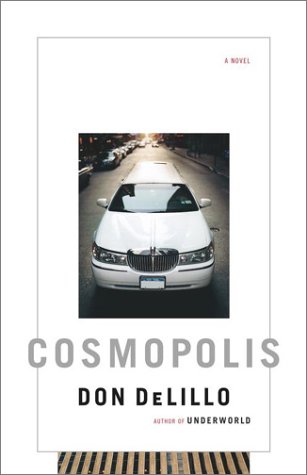

Cosmopolis by Don DeLillo

We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath ... a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath ... a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.--"The Futurist Manifesto," F.T. Marinetti

Beneath the data strips, or tickers, there were fixed digits marking the time in the major cities of the world. He knew what she was thinking. Never mind the speed that makes it hard to follow what passes before the eye. The speed is the point. Never mind the urgent and endless replenishment, the way data dissolves at one end of the series just as it takes shape at the other. This is the point, the thrust, the future.

--Cosmopolis, Don DeLillo

It struck me while reading Cosmopolis that perhaps if Marinetti, the founder of the Italian mindfuck philosophy that was Futurism, were alive today he would love this book. Marinetti wrote his manifesto in 1909, not long after the invention of the automobile, and one can only imagine what he would say if he could see today's cars, which make the racecars of one hundred years ago look tortoise-slow.

On the other hand, it may not be the automobiles which capture his imagination. In Cosmopolis, Don DeLillo places his anti-hero, multi-billionaire Eric Packer, in an automobile, one of the world's finest stretch limousines, but the power and speed of the vehicle is wasted in the novel-length crawl across the width of gridlocked Manhattan. It takes Packer an entire day (and novel) to accomplish his goal, which is to drive crosstown and get a haircut. On this interminable journey he is an observer to a presidential motorcade, a rapper's funeral, and a violent process, and a participant in a small handful of sexual escapades. All this traveling at what must be a fraction of a mile per hour!

But that is not to say that the limousine does not embody Marinetti's love of speed--though the limousine may be nearly stationary, it is the conduit through which Packer can monitor all facets of his global finance empire, through which information moves at speeds which would give Marinetti wet dreams.

In fact, information in Cosmopolis moves so quickly that it surpasses even real time. Take the security monitor inside the limousine, for instance, that shows Eric his actions a split second before he even commits them. Cosmopolis is a messy, sprawling novel (even at a slim 200 pp.) but I think that it can be whittled down to this idea, that in our modern era we live on the edge of precipice so razor-thin that we are in danger of falling off.

The Futurists wished to destroy the museums, which they considered graveyards; true art, they felt, must be continually and violently replenished and started anew. Cosmopolis seems to argue that we live in the Futurists' ideal world, that the tides of progress have moved on without us, past all human control. Packer's other mission during his limo ride, besides the haircut, is to pursue a bet against the yen, which despite his best efforts, rises impossibly. By the end of the novel, in a matter of hours, Packer is penniless. This, DeLillo says, is our reality: fortunes amassed and lost in afternoons, and getting faster all the time. As Marinetti says, "Time and Space died yesterday." And as the things that Marinetti cherished--the automobiles, the guns--seem almost antiquated to us, so Cosmopolis forces us to face our own hurtling toward obsolescence.

I think perhaps that Marinetti was born one hundred years too late. Cosmopolis is the ultimate Futurist novel, but also quintessentially 21st-century; it is so cutting-edge that it edges beyond even postmodernity. But this also nurtures, and perhaps necessitates, its biggest flaw: a severe lack of humanity. The awesome James Wood, writing for the New Republic, notes that "Eric is really no more than a vessel for theory; he is given not thoughts but meta-thoughts." How true. Here is a novel with much to say, but at times seems so drunk on its ideas that it forgets that ideas are only as relevant as the people they impact.

I struggled with this--after all, isn't this the point of it all, that the human being has become as passe as the Sony Walkman? But I remember DeLillo's White Noise, a novel that managed to break through the ominous haze of turn-of-the-century paranoia and find two people simply scared shitless of dying. Where White Noise had power, Cosmopolis has portentousness.

And besides, isn't the Futurist ideal fundamentally flawed? I recall a conversation I once had with an Italian professor of mine who noted that though the Futurists believed that mankind would become more and more like the technology they created in the automobile, in truth la macchina e stata humanizata--the automobile has become humanized. Though DeLillo taps into an essential modern fear about technology run amok, the fact is that our creations are becoming more and more like us instead of the other way around. Though we may feel obsolete, it cannot be ignored that those feelings are ours; our machines and software have no opinion.

DeLillo comes around toward the end of the novel, when Packer, in a plot point I've neglected to mention, comes face to face with a would-be assassin. Face-to-face with the barrel of a gun, Packer recalls that he'd "always wanted to become quantum dust, transcending his body mass, the soft tissue over the bones, the muscle and fat. The idea was to live outside the given limits, in a chip, on a disk, as data, in a radiant spin, a consciousness saved from void."

There, confronting death like the protagonists of White Noise, Packer comes to realize from what stuff he really is made:

The things that made him who he was could hardly be identified much less converted to data... So much come and gone, this is who he was, the lost taste of milk licked from his mother's breast, the stuff he sneezes when he sneezes, this is him, and how a person becomes the reflection he sees in a dusty window when he walks by. He'd come to know himself, untranslatably, through his pain... His hard-gotten grip on the world, material things, great things, his memories true and false, the vague malaise of winter twilights, untransferable, the pale nights when his identity flattens for lack of sleep, the small wart he feels on his thigh every time he showers, all him, and how the soap he uses, the smell and the feel of the concave bar make him who he is because he names the fragrance, amandine, and the hang of his cock, untransferable, and his strangely achy knee, the click in his knee when he bends it, all him, and so much else that's not convertible to some high sublime, the technology of mind-without-end.

Friday, November 7, 2008

The Year of Living Biblically by A. J. Jacobs

I remember hearing a couple of years ago about A. J. Jacobs, the guy who spent a year reading through the entire Encyclopedia Britannica and then wrote a book about it. I always sort of planned on reading that book, but I never got around to it. Then a couple of months back, I stumbled across this video teaser for Jacobs' The Year of Living Biblically. For this book, Jacobs read through the Bible (various versions) and wrote down every rule or guideline that he came across. He then spent the next year trying to adhere to this list of rules. Intriguing.

I remember hearing a couple of years ago about A. J. Jacobs, the guy who spent a year reading through the entire Encyclopedia Britannica and then wrote a book about it. I always sort of planned on reading that book, but I never got around to it. Then a couple of months back, I stumbled across this video teaser for Jacobs' The Year of Living Biblically. For this book, Jacobs read through the Bible (various versions) and wrote down every rule or guideline that he came across. He then spent the next year trying to adhere to this list of rules. Intriguing.I grew up in a family of religious conservatives who interpreted the Bible literally -- as far as I know they still do. Actually, it wasn't just my family, but many of the people I was in contact with on a day to day basis. Friends. Teachers. Neighbors. Even as a kid, I remember reading specific verses in the Bible and thinking, Okay, this doesn't make sense. If one simply takes the Bible at face value many books pose a lot of problems. For example, just try to follow all the rules laid down in Leviticus. Now some people say that Jesus wiped out many of the Old Testament laws, especially the ones regarding animal sacrifice. But there are a lot of other laws that don't have to do with sacrifices, such as the one is the teaser video, or Deuteronomy 21 which permits the stoning of a son or daughter that is rebellious or a glutton. Hmmm...things like this don't seem to jive with New Testament message of love and peace.

Jacobs comes to much the same conclusion. He prefers "Cafeteria Christianity." This is a derisive name that biblical literalists use to describe Christians that pick and choose from the Bible. I like the term too. There are some good things about the Bible, but you can't delude yourself into thinking that you can follow it in all of its precepts.

I was surprised at the level of respect that Jacobs maintains throughout the book. There are no "David Sedaris" descriptions of the people he encounters, no matter how crazy there beliefs may seem. In fact, Jacobs seems to find the silver lining in most of these beliefs. Not only that, but he does an alarming amount of research, both reading and talking with various religious people. This is not to say that the book is not funny. Jacobs has a good feel for what is funny, and his writing it witty. He just refuses to get his laughs from simply poking fun. Obviously, some of the situations were inherently funny. I particularly enjoyed his description of his trip to the Creation Museum, which is about twenty minutes from where I live.

At times this book reminded me of why I distanced myself from the way I was raised, but most of the time it was just a fun read.

Incidentally, Jacobs contributed an essay to Things I've Learned from Women Who've Dumped Me.