Surrounded by that ice and snow, Erasmus dreamed of home--less and less often, though, as the brig passed down Lancaster Sound. Around him were breeding gulls and terns, snow geese and murres, eiders and dovekies; the water thick with whales and seals and scattered plates of floe ice; a sky from which birds dropped like arrows, piercing the water's skin. Sometimes narwhals tusked through the skin from the other side, as if sniffing the solitary ship. They hadn't seen another ship since passing a few whalers at Pond's Bay, yet Erasmus was far from lonely. Dazzled, he looked at the cliffs, and knew Dr. Boerhaave shared his dazzlement.

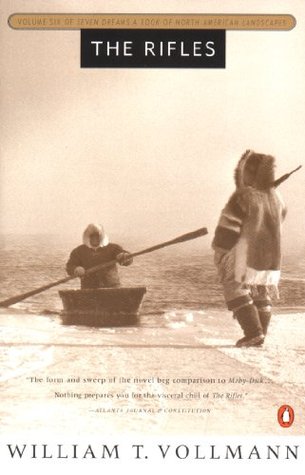

I love the Arctic. I'll probably never go there. Few people do. But I like reading about it, probably because it is so improbable: remote, harsh, difficult to access and inimical to comfort, the Arctic retains something of the feeling of the old frontier. No wonder that, in the 19th century, once the world had been more or less mapped, those who had explorers' hearts and minds turned to the Arctic; and for once they were pretty roundly defeated. Some of the Arctic's mystique, actually, comes from the fact that there are people who make it their home, and live lives of remarkable resilience there, not just against harsh conditions, but against the predations of people who think they know better. So it's a joy to read about, whether in The Rifles by William T. Vollmann, who was defeated by the Arctic like his alter ego John Franklin, or in Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez, a guy who knows more about the Arctic and its residents because he affords them a bit of basic respect.

Andrea Barrett's The Voyage of the Narwhal is a fiction book about an Arctic voyage gone, as all of them go, wrong. Its protagonist is Erasmus Wells, a middle-aged naturalist who signs on under Zeke Voorhees, a younger man and Erasmus' old friend. Zeke turns out to be a bad captain: he cares more about his own ambitions than the safety of his crew, and this ambition, mixed with a mercurial temper and plain poor judgment, leads to the Narwhal becoming stuck in pack ice. Like, they suspect--and we now know--the doomed Franklin expedition, of which the Narwhal is searching for evidence. Zeke's heedlessness kills, perhaps indirectly, several members of the voyage, and when the crew refuses to go on an ill-advised sledge excursion, Zeke goes by himself. When he fails to return, Erasmus takes the only opportunity to get out of the pack ice--lest they be frozen in for another year--leaving Zeke for dead.

That's all all right. I wouldn't say that Barrett has the knack for describing these alien landscapes like Vollmann and Lopez. Far more interesting, I thought, was what happens when Erasmus returns to Philadelphia. As it turns out, Elisha Kent Kane's Arctic voyage returned just before the crew of the Narwhal, having mapped first every bit of coastline the Narwhal thought they'd discovered. Erasmus returns basically empty-handed, and while Kane tours the country with tales of his exploits, Erasmus is either forgotten or loathed for having abandoned Zeke.

All this gets worse when, as any reader surely expects, Zeke shows up again, this time with an Greenlandic woman and her son in tow. According to Zeke's rendition, the pair have accompanied him voluntarily, but Erasmus suspects that there has been some coercion involved; that Zeke knew his only chance at notoriety was to bring back real life "Esquimaux." I wonder if Barrett was thinking of the Inuit woman and her son that caused such a stir in London. Like that real-life pair, Zeke's Greenlanders--Annie and Tom--grow quickly sick in the unfamiliar climate, and Zeke treats them shabbily, as curios to be shuffled onto the stage and then crammed in a drawer when not in use. Annie dies. Erasmus, working doggedly on a natural history of the Arctic--a book that lies in contrast to the dazzling half-truths of Kane and Zeke--decides that he must right Zeke's wrongs, and steals away on one final voyage to the Arctic, to return Tom to his family.

So there's a whiff of white saviorism to Erasmus' noble deed. But there's also a powerful critique of the way that natural philosophy has been practiced, of the cruel tools used to expand human knowledge. Zeke's methods are inhuman, murdering and despoiling the very places and people he claims as the field of his exploration. On the other hand, Erasmus represents another kind of scientist: humble, cautious, empathetic, and more interested in pursuing what is true and good than becoming celebrated. The book never tells us whether his natural history of the Arctic finds success; if it does, it probably still pales in comparison to the fame that the real-life Kent and the fictional Zeke claim. But the Arctic doesn't suffer fools, and perhaps like Franklin, they too will meet the ill consequences of their own recklessness.