"...Allah created this earthly realm so that, above all, it might be seen. Afterward, He provided us with words so we might share and discuss with one another what we've seen. We mistakenly assumed that these stories arose out of words and that illustrations were painted in service of these stories. Quite to the contrary, painting is the act of seeking out Allah's memories and seeing the world as he sees the world."

Orhan Pamuk's My Name is Red is, at its simplest, a murder-mystery: someone has murdered Elegant Effendi, one of the miniaturist illustrators tasked by the Ottoman Sultan to illustrate a great book which will be given as a present to the Venetian Doge. Pamuk puts us in the point of view of the murdered miniaturist, who narrates the unpleasantness of his death, and then, in the next chapter, the point of view of the murderer. (Cannily, of course, not telling us who he is.)

There are chapters from the point of view of the protagonist, Black, charged by his Uncle with finding the murderer; there are chapters from the point of view of his beloved, the beautiful Shekure; there are chapters from the point of view of multiple ancillary characters, and even a few of the illustrations themselves. ("I don't want to be a tree," a drawing of a tree tells us, "I want to be its meaning.") There are even, as the title suggests, chapters from the point of view of colors.

Both the murderer and his victim tell us that the murder was sparked by an anxiety about the propriety, under Islamic law and theology, of the book, and perhaps of illustration itself. My Name is Red grapples with the relationship between God and art, under the often iconoclastic framework of Islam. Is it a sin to depict the world realistically, as the Frankish painters do? Is it hubris to paint, as the old masters do, through memory and repetition, trying to reproduce the world as it is seen in the eyes of Allah? There is much talk about what it means to draw a horse, and whether to draw a horse that one sees, or the horse that Allah has imagined.

I love that kind of stuff, and, for me, what was most interesting about My Name is Red was being forced to think about in a religious context that is ultimately foreign to me. There are iconoclastic traditions in Christianity, too, and plenty of books that deal with them, but only Islam could provide the framework for this book. Pamuk mines from Islamic tradition innumerable stories which are told in the illuminated manuscripts the miniaturists create, new to me, but certainly as familiar to his own audience as Abraham and Isaac, or Jacob and Esau are to me. I liked being pushed outside of my comfort zone in that way.

Thursday, December 31, 2015

My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk

Labels:

islam,

My Name is Red,

Orhan Pamuk,

turkey

Wednesday, December 30, 2015

The Collapse of American Criminal Justice by William J. Stuntz

. . . legal doctrines play an important role in the sad story of American criminal justicem and they play an important role in this book. But their role is strange and widely misunderstood: law serves chiefly as a means of giving law enforcers greater discretion and more power to exercise it. Regulating the conduct of those law enforcers is mostly left to politics and politicians. This perverse partnership between law and politics has produced many of the system's worst injustices. The tendency, especially among lawyers, is to think that the chief remedy for those injustices lies in more law--especially more constitutional restrictions on the government's ability to police and punish crime. The thought has some merit: the right kind of constitutional restrictions would make for a better and fairer justice system. Even so, the more urgent need is for a better brand of politics: one takes full account of the different harms crime and punishment do to those who suffer them--and one that gives those sufferers the power to render their neighborhoods more peaceful, and more just.

. . . legal doctrines play an important role in the sad story of American criminal justicem and they play an important role in this book. But their role is strange and widely misunderstood: law serves chiefly as a means of giving law enforcers greater discretion and more power to exercise it. Regulating the conduct of those law enforcers is mostly left to politics and politicians. This perverse partnership between law and politics has produced many of the system's worst injustices. The tendency, especially among lawyers, is to think that the chief remedy for those injustices lies in more law--especially more constitutional restrictions on the government's ability to police and punish crime. The thought has some merit: the right kind of constitutional restrictions would make for a better and fairer justice system. Even so, the more urgent need is for a better brand of politics: one takes full account of the different harms crime and punishment do to those who suffer them--and one that gives those sufferers the power to render their neighborhoods more peaceful, and more just.Welcome to my fourth installment of my Criminal Justice Policy Book Review Series. In this installment, we review William J. Stuntz's posthumous magnum opus, The Collapse of American Criminal Justice. If I had to distinguish this book from the others I've reviewed, I'd say it's the most comprehensive. Definitely more for an academic audience (maybe less so than Murakawa's book, but still up there), but also covers substantially more ground.

Stuntz begins his book by describing a puzzling phenomenon: today, crime is up, incarceration is up, and the sense of injustice over this system is, well, up. But, this was not always the case--indeed, comparatively speaking our criminal justice system today is something of a historical curiosity item. So, like, what gives, right? Stuntz identifies three keys: "First, the rule of law collapsed . . . . Second, discrimination against both black suspects and black crime victims grew steadily worse--oddly, in an age of rising legal protection for civil rights . . . . The third trend is the least familiar: a kind of pendulum justice took hold in the twentieth century's second half, as America's justice system first saw a sharp decline in the prison population--in the midst of a record setting crime wave--then saw that population rise steeply."

The book, taking different trends and parts, starts with Reconstruction and follows the development of criminal justice in this country up to today, drawing a contrast between what Stuntz thinks of as a better--albeit not perfect--system (immediately following Reconstruction) to our system today. I'm only going to discuss one of Stuntz's points that was particularly compelling for me. Nonetheless, this book is worth reading for the numerous, other discussions that are thought provoking like:

- Why the migration of Europeans to urban areas had a different effect on crime than the migration of southern blacks to northern cities.

- How our system of imprisonment came to incarcerate so many people, including a disproportionate number of African Americans.

- The rise of prosecutorial discretion, as seen between two different issues of federal criminal law, polygamy and state lottery systems.

- The rise of procedure at the expense of substantive review of crime.

|

| William J. Stuntz |

The topic that most fascinates me about Stuntz's book is the relationship between localized control over crime and centralized control over crime. Stuntz describes that over the last one hundred years, control over the criminal justice system shifted away from municipalities and towards county, state, or federal governmental bodies. However, with this shift comes less voter control over criminal justice. Thus, Stuntz writes: "Growing centralization lessened the power of the voters who bore the brunt of crime and criminal punishment alike: meaning, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, urban blacks." So the neighborhoods most affected by law enforcement, prosecutors' offices, and imprisonment, have little to no say over the very policies dictating these laws.

As a thought experiment, I wanted to look at Clark County, Nevada. The data I've accessed is...imperfect, but I suspect even with perfect data, the conclusions would look the same. Clark County, Nevada has a population of roughly two million people (1,951,269 as of 2010 census). In 2010, the D street neighborhood (incidentally,where my office is) was listed as the 8th most dangerous neighborhood in the United States, covering the 89106 and 89101 zip codes. The district attorney received 224,919 votes to win in 2014(72% of the vote) (disclaimer: he did not have a serious challenger) (second disclaimer: he was an incumbent running in a low voter turnout election).

According to this sketchy website I found, 89106 has about 25,000 people living in it; 89101 has roughly 90,000 people living in it. It's difficult to interpret anything with such low voter turnout, but even assuming everyone in these two zipcodes could vote and did vote, they would not come close to being able to elect a district attorney (assuming, of course, they would want a different district attorney). Admittedly, with such unreliable data, and data that is not neighborhood specific, it's hard to draw any conclusions. That said, I would be incredibly interested in more data.

Nonetheless, Stuntz's point is interesting. In Nevada, judicial elections as well as district attorney elections are county-wide (well, technically by judicial district...which usually follows the county line). Thus, in addition to prosecutorial decisions, sentencing decisions are made by candidates elected by the county--which here means both voters in the suburbs and voters in the neighborhoods actually affected by crime. This, to me, seems a big problem. Though, I'm not sure how realistic it would be to even try to make a change to this practice. Nonetheless, shouldn't prosecutors and judges making decisions about whom to prosecute and whom to punish be politically liable to a localized electorate? (Of course, assuming we want judges to be elected at all).

I think part of what interests me in Stuntz's criticism is a concept Hannah Arendt developed, the vita activa (i.e., politically active life). For Arendt it is extremely important in a society for everyone to be politically active. Stuntz describes a system that politically silences the population most affected by criminal justice policy. Here, as in the other areas of his book, Stuntz both describes a problem and possible solution, and leaves to the reader to wonder how to implement it. I'm still wondering.

Stay tuned, I'm sure there's going to be another criminal justice book (maybe even 8) in my future.

The Wake by Paul Kingsnorth

oh i can sae these words and try to tell what it was like there but naht can gif to thu what was in my heorte as i seen all of this cuman in to place. sum folcs who is dumb thincs the world is only what can be seen and smelt and hierde but men who cnawan the world cnawan there is a sceat of light that is betweon this world and others and that sum times and in some places this sceat is thynne and can be seen through. on this daeg in this ham the sceat was thynne and scriffran in the light wind and through it i colde see that all the world triewely was beyond this small place of small men and deorc and strong and of great beuty and fear was what i saw

[Oh, I can say these words and try to tell what it was like there, but nothing can give to you what was in my heart as I saw all of this coming into place. Some folks who are dumb think the world is only what can be seen and smelled and heard but men who know the world know there is a sheet of light that is between this world and others and that sometimes and in some places this sheet is thin, and can be seen through. On this day in this town, the sheet was thin and shivering in the light wind, and through it I could see that all the world truly was beyond this small place of small men and dark and strong and of great beauty, and fear was what I saw.]

Paul Kingsnorth's The Wake is a dystopian novel set not in the distant future but the distant past: England, circa 1066, before, during, and after the Norman conquest. Its protagonist, Buccmaster, is a middling landowner in a small village who sees his sons go off to war against William the Conqueror, never to return, and then whose home is destroyed and wife killed when he refuses to pay the gold the new French authorities require. Like The Road, it is about a moment of utter transformation; the world as Buccmaster knows it has disappeared, replaced with something bleak, foreign, and tragic. Here he pauses to consider the ways that the French will rename the very places that he has lived his entire life:

All that is true: the life that Buccmaster has known is gone, his wife and family dead, his home burnt to the ground. But in subtle ways The Wake undermines the very idea that such a drastic obliteration, or historical break, is possible. One is in the very language itself. Kingsnorth writes in a kind of pidgin Old English, avoiding any word whose roots weren't present in English before 1066. Like Riddley Walker, the strange language alienates us from the narrator and emphasizes the distance, backward or forward in time, between us and him. But the very fact that the language is comprehensible--it's not Old English, of course, but a kind of highlighting of the Old English that remains with us in our present language--emphasizes what has remained of Buccmaster's civilization, rather than what has been lost. The irony of Buccmaster's elegy for the very trees of his land is that that good old Anglo-Saxon word treow is still what we use for our trees, not the Norman French.

Buccmaster gathers a small band of the dispossessed and flees to the woods, the holt, to fight the French in petty skirmishes. He fights not for the England that is disappearing, but one that has long since disappeared--the England of the pagan gods which is grandfather worshipped. But England has become Christianized, since long before the Normans arrived. For Buccmaster, the two breaks are the same: the conquest of Christ and the conquest of the Normans. It's for these reasons that he and his ragtag crew kidnap and terrorize a bishop en route through the countryside, rather than, say, raiding a French castle.

But most of the time Buccmaster doesn't do anything at all. He stays in the holt, dreaming of his own great role in the reconquest of England, refusing to take any kind of material action at all while his crew chafes at both his idleness and his love for pagan gods. He receives a number of visions, which in some dystopian novels might mark him as a "Chosen One," but here slowly reveals him to be a delusional megalomaniac. As the novel subverts the tropes of invader and invaded--Empire and Rebel Alliance, if you will--it mocks the provincial inability to deal with change. And it does that while never losing sight of the reality of the tragedy that befell the English in 1066, whose lives really were turned upside down with unprecedented suddenness and severity.

[Oh, I can say these words and try to tell what it was like there, but nothing can give to you what was in my heart as I saw all of this coming into place. Some folks who are dumb think the world is only what can be seen and smelled and heard but men who know the world know there is a sheet of light that is between this world and others and that sometimes and in some places this sheet is thin, and can be seen through. On this day in this town, the sheet was thin and shivering in the light wind, and through it I could see that all the world truly was beyond this small place of small men and dark and strong and of great beauty, and fear was what I saw.]

Paul Kingsnorth's The Wake is a dystopian novel set not in the distant future but the distant past: England, circa 1066, before, during, and after the Norman conquest. Its protagonist, Buccmaster, is a middling landowner in a small village who sees his sons go off to war against William the Conqueror, never to return, and then whose home is destroyed and wife killed when he refuses to pay the gold the new French authorities require. Like The Road, it is about a moment of utter transformation; the world as Buccmaster knows it has disappeared, replaced with something bleak, foreign, and tragic. Here he pauses to consider the ways that the French will rename the very places that he has lived his entire life:

now in this small holt by bacstune locan at the treows i was thincan that these frenc they wolde gif all these things other names. i was locan at an ac treow and i put my hand on its great stocc and i was thincan the ingengas will haf another name for this treow. it had seemed to me that this treow was anglisc as the ground it is grown from anglisc as we who is grown also from that ground. but if the frenc cums and tacs this land and gifs these treows sum frenc name they will not be the same treows no mor.

[Now in this small wood by Bacustune, looking at the trees, I was thinking that these French, they would give all these things other names. I was looking at an oak tree and I put my hand on its great trunk and I was thinking the foreigners will have another name for this tree. It had seemed to me that this tree was as English as the ground it is grown from, English as we who are grown also from that ground. But if the French come and take this land and give these trees some French name they will not be the same trees anymore.]

All that is true: the life that Buccmaster has known is gone, his wife and family dead, his home burnt to the ground. But in subtle ways The Wake undermines the very idea that such a drastic obliteration, or historical break, is possible. One is in the very language itself. Kingsnorth writes in a kind of pidgin Old English, avoiding any word whose roots weren't present in English before 1066. Like Riddley Walker, the strange language alienates us from the narrator and emphasizes the distance, backward or forward in time, between us and him. But the very fact that the language is comprehensible--it's not Old English, of course, but a kind of highlighting of the Old English that remains with us in our present language--emphasizes what has remained of Buccmaster's civilization, rather than what has been lost. The irony of Buccmaster's elegy for the very trees of his land is that that good old Anglo-Saxon word treow is still what we use for our trees, not the Norman French.

Buccmaster gathers a small band of the dispossessed and flees to the woods, the holt, to fight the French in petty skirmishes. He fights not for the England that is disappearing, but one that has long since disappeared--the England of the pagan gods which is grandfather worshipped. But England has become Christianized, since long before the Normans arrived. For Buccmaster, the two breaks are the same: the conquest of Christ and the conquest of the Normans. It's for these reasons that he and his ragtag crew kidnap and terrorize a bishop en route through the countryside, rather than, say, raiding a French castle.

But most of the time Buccmaster doesn't do anything at all. He stays in the holt, dreaming of his own great role in the reconquest of England, refusing to take any kind of material action at all while his crew chafes at both his idleness and his love for pagan gods. He receives a number of visions, which in some dystopian novels might mark him as a "Chosen One," but here slowly reveals him to be a delusional megalomaniac. As the novel subverts the tropes of invader and invaded--Empire and Rebel Alliance, if you will--it mocks the provincial inability to deal with change. And it does that while never losing sight of the reality of the tragedy that befell the English in 1066, whose lives really were turned upside down with unprecedented suddenness and severity.

Monday, December 28, 2015

Brittany's Top 11 of 2015

|

| Not Pictured: Everything I Never Told You |

By The Numbers

- 67 complete books read (9 children books, 12 middle reader books, 16 young adult, 8 graphic novels, 13 non-fiction books or memoirs, 2 short story collections, and 4 narratives written in poetry)

- 30 books were read for grad school

- 64 authors (repeats include Ernest Hemingway, Haruki Murakami, Ian McEwan, Donna Tartt, and Lenore Look while some graphic novels had multiple authors)

- 26 male authors, 37 female authors, and 1 I am not sure of and don't want to misgender

- 4 dead authors, 60 living (RIP A. A. Milne, E. B. White, Chester Nez, Ernest Hemingway)

- 8 nationalities (American, British, Lebanese, Russian, Canadian, Japanese, French, Afghani)

- 3 American Indian authors (from the Navajo, Spokane, Coeur d'Alene, and Laguna Pueblo tribes)

Top Books

This year's list was the hardest because the books I read were so different and I found myself making absurd brackets like "Which is better? The non-fiction Pacific Crest Trail memoir Wild or the middle reader narrative poem about basketball and family The Crossover?" and then eliminating both even though I thoroughly enjoyed and would recommend both.

I also didn't do a lot of book reviews this year, so I had to read summaries of books like And the Mountains Echoed and Colorless Tsukuru Taziki and His Years of Pilgrimage and try to remember how they made me feel. I liked them both and would count both Hosseini and Murakami as among my favorite authors, but could their books really be top books if I couldn't remember them without a review?

The last thing I'll say before I get to the list is apparently I have unofficial categories in my head for books that are on my top list. For the past two years my top lists have included a Book About Race (Americanah and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl), A Fucked Up Book (Dark Places and Gone Girl), A Classic I Should Have Read Already (Handmaid's Tale and Portrait of a Lady), a Pulitzer Winner/Nominee (Three Plays and A Visit from the Goon Squad), A Non-Fiction Book About a Topic More People Should Know About (Into Thin Air and Maus), a Book of Interconnected Stories with Shifting Narrators (Suite Francaise and A Constellation of Vital Phenomena), and this year's list seems to include the same unofficial categories.

1. Dante and Aristotle Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Saenz: My only regret is that this book wasn't around when I was in high school. If it were, this would be a book that defined me. It won a million awards including two LGBT awards, one Latino award, and was a Printz Honor Book, which is one of the most important young adult awards. If you're only going to read one YA book, this should be it. Taking place in El Paso, Texas, in 1987, it focuses on the friendship of Ari and Dante. Ari is an angry, lonely teen who has questions about his incarcerated brother that his parents pretend never existed. Dante is a dreamer and an artist. The writing is beautiful, the story is compelling, Dante and Ari's friendship is admirable, and I especially related to Dante and Ari's conversations about what it means to be a 'real Mexican.' The book's popularity will hopefully demonstrate to publishers that a book filled with minority characters can reach a broader audience with universal themes about love, family, and friendship. It is young adult literature at its best.

2. The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt: This Pulitzer prize winning novel is on many top lists and deservedly so. The writing is beautiful, the characters are always interesting and compelling (even if our protagonist is kind of a jerk), and the story seems to particularly resonate with our time as it follows the aftermath of surviving a terrorism attack. It also has a special place in my heart because I don't think I have ever loved reading about a dog as much as I loved reading about Popper (and I read Laika and Dash this year - two dog-focused middle readers that both made me cry). I don't usually want to reread long books - let's be honest, rereading this 800 page book really means I will read 5 fewer books in my lifetime, but I do look forward to revisiting this book again and determining if it is a Great Novel.

3. The Color Master by Aimee Bender: This short story collection brought me right back to my first experience reading Bender. Each story contains a sensualness or loneliness or frequently a strange concoction of both. There are no duds in the collection, and while they each stand up alone, together they show Bender's talent in telling completely different kinds of stories that all have the same loveliness. Randy asked if I would recommend this, another collection, or one of her novels for someone looking to read Bender for the first time, and back then I suggested An Invisible Sign of My Own. Now I would recommend this one - I think it is Bender at her best.

4. The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern: After reading this fantasy romance, I wanted to wear black and white and red for weeks so everyone would know I was a reveur. Two magicians each take on an apprentice who must compete within the arena of the night circus. The descriptions of their magical concoctions are imaginative and just close enough to being possible that the reader is devastated to realize the Night Circus will never mysteriously pop up in town. The story is told in a non-linear fashion with shifting perspectives, which I am always a fan of, and Morgenstern manages to maintain high interest in each and every perspective. When I was out of books on a camping trip, I found myself re-reading it and it was HARD TO PUT DOWN even though I had just read it.

5. And the Mountains Echoed by Khaled Hosseini: Every novel Hosseini writes I love and find equally important. After I read the Kite Runner, I thought it was a great book about an important story that people needed to hear. Then I read A Thousand Splendid Suns and I thought it was a great book about a different important story that people needed to read. When people asked for a recommendation, I would tell them to read The Kite Runner if they wanted to read about men and A Thousand Splendid Suns if they wanted to read about women. And the Mountains Echoed surpasses both books and has a more diverse cast that will grip any reader. It encompasses over fifty years of time and traces several stories from the workers to the warlords to the refugees.

6. Push by Sapphire: I don't think I'm giving too much away when I say that this is one of the most depressing novels of all time, but it's an important story and one that people need to read. There are plenty of books about white women working in urban schools and saving students, but there are not enough books about the actual lives of the actual kids who go to those schools. Sapphire does an excellent job of giving a voice to Precious that is real (based on her own experiences as a teacher) without feeling exploitative or condescending. This book is definitely not for everyone, but more people should read it than do.

7. The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway: This novel showed me that Hemingway is not overrated and that I don't hate him. I carried a strict anti-Hemingway prejudice deep in my heart for a decade and never managed to get over it (which, with a minor in English and an MA in English is no small feat). Reading a book by Big Poppa and loving it was a revelation.

8. Alex by Pierre Lemaitre: This book is messed up and I loved it. It's a book I would recommend to people who like Gillian Flynn and Stieg Larsson, but I wouldn't talk about too much because I don't want people to think I'm a sociopathic serial killer. Alex is the first in a series that is being published and translated fairly quickly, giving you something to read in between Flynn novels, and Lemaitre is still alive, so he beats Larsson there (although I have not read the new David Lagercrantz contribution to the series, so I can't say whether or not Larsson's vision lives on).

9. Code Talker by Chester Nez: After spending a night in Tuba City and checking out various Navajo/Dine museums and sites, I wanted to read a book that would give me even more of an in-depth perspective. The subtitle says "The first and only memoir by one of the original Navajo code talkers of WWII" which was persuasive enough for me. I am not a WWII buff and I have actually never read a military book before, but I couldn't put this down. It covers Nez's whole life, not just the war years, and demonstrates just how amazing the code talkers' work was, especially in contrast to how awful American Indians were treated.

10. Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng: This novel attempts to do so many different things and manages to do them all well. It opens on the mysterious death of a teenage girl (we know from the first page where and when her body will be found), and sustains the intrigue resulting from that. It is a family drama, and the shifting perspectives of different family members is so real (but much more compelling than our own family's dramas). It is a historical fiction, covering the 1950s-1970s. It is absolutely a novel about race, but it's also a text about gender norms, and it's also just a story about an American family dealing with loss. This was a book club pick, and even after discussing it for two hours I still felt like I had a lot to think about.

11. Modern Romance by Aziz Ansari: This has been the most recommended book of the year (that is, I have recommended it to basically everyone I know). Ansari pairs up with sociologists and psychologists and old people and young people to try to figure out what romance used to mean and what it means now, in an age where you can swipe through thousands of potential partners and still be completely alone in the world. Ansari can basically do no wrong in my world, from his stand up to this book to his Netflix show Master of None. If a person likes any of his other work or has ever done online dating, I would definitely recommend this book.

Honorable Mentions

- I have so much love for Akata Witch by Nnedi Okorafor and I hope it becomes as popular as other YA fantasy phenomenons. A secret school of magic for teenagers in Nigeria - anyone who likes series such as Harry Potter, A Clockwork Angel, or Cinder should be stoked that the sequels are already in the works.

- Code Name Verity by Elizabeth Wein is another YA book - this time a historical fiction novel - that I have recommended to anyone I know who reads YA. The time is WWII, the characters are two best friends - a pilot and a spy - and I couldn't put it down. Readers will be relieved that there is no love triangle (there actually isn't any romance at all - our two badass heroines are too busy trying to help win World War II!). The sequel, Rose Under Fire, is already out and the Twittersphere says it's just as good if not better than the first.

- The Secret History by Donna Tartt gave me a lot of trouble when making this list. I loved The Goldfinch. I loved The Secret History. I couldn't put either down. I almost paired them up in the number two spot, but they are too different to put together. Ultimately I decided to give the list spot to The Goldfinch because I can see myself reading it again, over and over, in my life. I might have one reread of The Secret History left in my life, but I would definitely reread The Goldfinch first. It's an arbitrary standard (after all, I don't think I'll ever reread Code Talker and that made it on the list), but a decision needed to be made.

Top 5 Books I Didn't Count

I took a children's lit class this semester which put me in the situation of having to define what 'counted' as a 'book.' For the purposes of this blog, I counted the book if it was 100 pages or longer. I read 30 books that didn't meet this standard, but I have opinions about them nonetheless.

1. Waiting is Not Easy by Mo Willems: Anyone with children under the age of 10 has surely heard of Mo Willems. The only thing under the age of 10 in this house is my boston terrier, so I had not. I haven't read his most popular book, Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus, but I have read a few, and Waiting Is Not Easy is my favorite. The message is great for kids, the artwork is simple but lovely, and I love what elephant and piggy are waiting for.

2. Separate Is Never Equal by Duncan Tonatiuh: My classmates definitely got tired of hearing me talk about this one. Tonatiuh's art is amazing, as it is in all his works, but the content of this non-fiction picture book is even better. It details the story of Sylvia Mendez's family who is responsible for desegregating California schools way before Brown v. Board of Education. As a Hispanic teacher living and teaching in the Southwest, in a school district where Hispanics are the majority, I am ashamed and angry that I had never heard of Mendez v. Westminster before reading this book.

3. Little Roja Riding Hood by Susan Middleton Elya: A retelling of little red riding hood that incorporates rhyming Spanglish (it never occurred to me that abuela and telenovela rhymed before reading this) and modern ideas. Abuela and Roja save themselves and take practical measures to further protect themselves from big bad wolves.

4. Nino Wrestles the World by Yuyi Morales: Partly just an excuse to give my nieces and nephew a luchador mask, this book has the most amazing artwork and incorporates Mexican folklore into an imaginative tale about a little boy who loves to wrestle. I realize that three of my five books are about Hispanic families written by Hispanic authors (and all three were books I read outside of class). This has to be more than a coincidence, and I wonder if part of why I love these books so much is because when I was a kid, these books didn't exist, so as an adult they are extra exciting to me?

5. The Adventures of Beekle the Imaginary Friend by Dan Santat: One of the most beautiful picture books I read this year and the story is also charming. Every pot has its lid, every imaginary friend has its person, and sometimes we need to take matters into our own hand to find our person.

Sunday, December 27, 2015

Christopher's Top Ten of 2015

Christopher's Top Ten of 2015

10.) Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed - I almost put a number of other books in this slot, including the two excellent short story collections by Ernest Hemingway, Jorge Luis Borges, and Stanislaw Lem. But I chose Reed's Mumbo Jumbo because it's just so unlike anything else I've ever read. Cobbled together from from history books, jazz lyrics, and Voodoo legends, Mumbo Jumbo merrily skewers the sacred cows of Western (that is, white) culture, contrasted by the Jes Grew, a dance craze that springs up amid black America and which is half social movement and half contagious epidemic.

9.) The Second Coming by Walker Percy - Like The Moviegoer, The Second Coming is about two broken, mentally ill people who find comfort and belonging in each other's love. Both novels begin with cosmic searches--the protagonist of The Second Coming, Will Barrett, traps himself in a cave to see if God will save him--and end in a human embrace. Percy is often obscure but always profound, and the North Carolina setting struck a chord with me that The Moviegoer wasn't able to.

8.) Turtle Diary by Russell Hoban - As much as I love the consonance in Percy's books, I have a great admiration for a guy like Hoban, who never writes the same book, or even a book in the same stratosphere, twice. This one is about two strangers who come independently to the same conclusion: two sea turtles in the London Zoo must be stolen and set free. The set up is a meet-cute, but the book is not--the protagonists never fall in love, and by helping these animals reach their instinctual and ancestral home, they only find themselves a brief respite from what Lukacs calls our "transcendental homelessness."

7.) Swann's Way by Marcel Proust - Okay, I admit that to some extent Swann's Way's inclusion here is out of admiration and respect, rather than love. Is it possible to love In Search of Lost Time? The effect of looking in on the complex tapestry of someone's memory and consciousness seems alienating, rather than intimate. Proust's narrator is so thoroughly made that he gets beyond me, and Proust, and defeats any attempt to really know him. But Proust understands the shape of the human mind better than any other writer, and this novel is an achievement unlike anything else.

6.) Play It as It Lays by Joan Didion - This book contains my favorite sentence of the year: "Taco Bells jumped out at her." I described it in my review as a cross between The Bell Jar and Day of the Locust, which is kind of like that old Reese's commercial where the chocolate gets in the peanut butter (making it awesome). It's a blistering, dust-swept condemnation of Hollywood, and of American masculinity as a whole.

5.) Under the Net by Iris Murdoch - Didion and Murdoch are my two favorite new writers of the year: authors I had heard of, but never actually read. Now I'm excited to read the rest of their stuff. Under the Net is (literally) a shaggy dog tale, involving a mysterious mime play and a movie star dog named the Marvelous Mister Mars, among other things. But it's also somehow a meditation on Wittgenstein and the nature of language, as thought-provoking as it is amusing.

4.) The Transmigration of Timothy Archer by Philip K. Dick - Dick always manages to find away to surprise me. I always expect his novels to be clever, profound, and bonkers. I know they always manage to add one more crazy detail than it seems like they can withstand. But I've never read a novel from Dick as deeply, heart-breakingly human as this one, the story of a strong, kind man whose search of religious truth kills him and brings death and ruin to everyone around him. Dick believed some pretty insane things, but he was always unflinchingly honest and unsparing about belief itself. It's possible that this is his very best novel.

3.) Innocence by Penelope Fitzgerald - An almost perfectly realized novel. The main characters--a brash Roman doctor and a naive Tuscan countess--fall in love despite themselves, and endure a rocky courtship. Salvatore and Chiara are vivid, robust characters, but everyone in the novel is: Fitzgerald's principle gift, I think, is knowing how to populate a book with people that feel at once both real and interesting. There are only two more of Fitzgerald's books out there left for me to read, a fact which makes me pretty depressed. There really was no one like her.

2.) Delta Wedding by Eudora Welty - So I'm reading Go Set a Watchman, which partly exists to elaborate on the half-imaginary town of Maycomb, Alabama that Harper Lee clearly loves, for all its well-publicized transgressions. But it's Welty's Mississippi that manages to elevate the small town of the Delta into a place worthy of great literature, something vast, dreamlike, nearly mythological. Even Faulkner, whose The Unvanquished I'm going to review shortly, couldn't do what Welty did for the Delta. This story, about a family that comes together for the wedding of their oldest daughter Dabney, demands a slow and careful attention that I'm not used to. And Welty's prose is probably the most beautiful of any author on this list.

1.) Lila by Marilynne Robinson - ...except for maybe Marilynne Robinson, whose 2015 novel Lila picks up the threads of her previous novels Gilead and Home. I was really bored by Home, but Lila really recaptures what was so breathtaking about Gilead: the homespun prose, thrilling in its subtleties, the profound, yet humble meditation on what it means to actually live a life of faith. Robinson writes in her new collection of essays, The Givenness of Things, that the legacy of the Reformation is the idea that faith ought to take its promise to the poorest, most marginalized people, and Lila, the homeless, half-wild woman who is taken into the home of the Reverend Ames and becomes his wife, is the epitome of this idea. This novel cemented my belief that Robinson is the best writer we have in the English language today, and I think the President might agree.

That's a wrap! If you'd like to join us next year, shoot me an e-mail at misterchilton-at-gmail-dot-com. It's the best New Year's resolution you could make!

The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro

How will you and your husband prove your love for each other when you can’t remember the past you’ve shared?Randy was the first 50 Booker to read The Buried Giant in May. He loved the book, saying it "mixes the best of two worlds: the best of Ishiguro's writing with its subtle subversion between characters, whose reliability we cannot trust, and classic elements of fantasy tales, knights, plagues, ogres, and even sprites...Highly recommended"

Then Chris read it in June and disagreed with Randy, saying "Ishiguro seems to have no real idea of how to harness the possibilities of fantasy, or how to build a world which is specific and real...[it] reads exactly like what it is: a fantasy novel written by someone who never really reads fantasy novels."

In July I messaged Brett requesting a review because it was listed on his books, and then I messaged Billy and told him to read it because I thought it would be interesting if we all read the same book - especially since our readings this year have been all over the place. When Brett reviewed the book, he sided with Chris: "[In The Buried Giant] though, things don't really come together in a satisfactory way...I have to side with Ursula K. LeGuin and Chris. There are just too many weak links in the story for it to hit as hard as Never Let Me Go or Remains."

As in 50 books, so in life. This book is really divisive. NPR says it's "masterful...radiant and deeply moving." The New York Times calls it an important book that "does what important books do: It remains in the mind long after it has been read, refusing to leave, forcing one to turn it over and over." At the same time the reviewer says they were unable to fall in love with it. Ursula K. LeGuin famously blogged "it didn't work. It couldn't work...I found reading the book painful." The New Yorker also had some choice words, calling it "feeble...generic, and pressureless; and because its allegory manages somehow to be at once too literal and too vague - a magic rare but unwelcome."

I actually didn't know any of this when I started the book though. Randy told me to read it, I told everyone else to read it (and honestly, almost forgot until Billy asked me what I thought about it - oops), so I entered the book without any ideas. I did read Never Let Me Go ages ago, but I disliked it so much I never felt compelled to read another Ishiguro novel. I was very surprised to enter the world of the novel:

Icy fogs hung over rivers and marshes, serving all too well the ogres that were then still native to this land...such monsters were not cause for astonishment. people then would have regarded them as everyday hazards, and in those days there was so much else to worry about.

Thus it opens with ogres and fog and an old married couple, Axl and Beatrice, who decide to leave their village to visit their adult son in a nearby village. As they prepared to leave for their journey, which involved a lot of permission getting, supply gathering, waiting for appropriate weather, and of course forgetting what they were doing and why they were doing it:

In this community the past was rarely discussed. I do not mean that it was taboo. I mean that it had somehow faded into a mist as dense as that which hung over the marshes. It simply did not occur to these villagers to think about the past - even the recent one."

Once they started traveling, I realized I needed to read it like an epic or a pilgrimage, and I fell into pace with Axl and Beatrice and their travel companions and really began to enjoy it. In fact, I really liked 315 pages of it thoroughly. But the novel is 317 pages long. And as a reviewer this puts me in quite a pickle.

I'm not going to talk about the end of the novel, so let's go back to the beginning. In reviews of The Buried Giant, one of the arguments is whether the novel should be read as an allegory and what the meaning of that allegory is. When I started the book with the Never-Let-Me-Go-inspired-assumption that things were not as they seemed, I was frustrated and bored. The dialogue was slow and repetitive and what is the secret twisty meaning of it!?

"And why would you be after medicines, princess?" "A small discomfort I feel from time to time. This woman might know of something to soothe it." "What sort of discomfort, princess? Where does it trouble you?" "It's nothing. It's only because we're needing to shelter here I'm thinking of it at all." "But where does it lie, princess? This pain?"

(Full Disclosure: my parents have been married for over 30 years and if you took away the pet name and added a little more cursing, this is basically how they talk.)

So, again, once I fell into pace with Axl and Beatrice and stopped looking for secrets, twisty meanings, and symbolism, I really liked it. I totally didn't realize a creature was a dragon, and when the dragonness was revealed, I was delighted. I laughed when Sir Gawain's old ass appeared. I really enjoyed the intrigue of the monastery and the epic fight scene. I appreciated why political leaders made the choices they made in order to stop the wars that were devastating the Britons and Saxons even as I disagreed with them. I accepted everything that happened as literally happening and then when the last two pages literally happened I was emotionally wrecked and so so sad.

Reading many many reviews of The Buried Giant shows that most readers interpreted the ending allegorically. For the record, that makes a much better ending. But I'm reluctant to read that as an allegory because then I have to re-read everything as an allegory and I'm back to the beginning when I was trying to 'figure it out' and bored by the mental gymnastics of trying to give deeper meaning to everything. Although I liked the book much more than the New Yorker reviewer did, I have to agree that it is both too allegorical and yet not enough. Although I don't think I quite agree with the New York Times reviewer that it is an Important Book, I have thought about the book almost non-stop since I finished last night.

Monday, December 21, 2015

Reflections in a Golden Eye by Carson McCullers

'You mean,' Captain Penderton said, 'that any fulfillment obtained at the expense of normalcy is wrong, and should not be allowed to bring happiness. In short, it is better, because it is morally honorable, for the square peg to keep scraping about the round hole rather than to discover and use the unorthodox square that would fit it?'

'Why, you put it exactly right,' the Major said. 'Don't you agree with me?'

'No,' said the Captain, after a short pause. With gruesome vividness the Captain suddenly looked into his soul and saw himself. For once he did not see himself as others saw him; there came to him a distorted doll-like image, mean of countenance and grotesque in form. The Captain dwelt on this vision without compassion. He accepted it with neither alteration nor excuse.

The comparison I reached for immediately while reading Carson McCullers' Reflections in a Golden Eye is the "four-square house" of The Good Soldier, which comes tumbling down when John Dowell realizes that his wife and best friend have been carrying on an affair for years. But the "four-square house" of Reflections in a Golden Eye is rotten and termite-ridden to the core: its four pillars--two officers and their wives on a Southern army base during peacetime--already aware of the affair going on among them, and seething with loathing. McCullers transforms Edwardian reserve and gentility into Southern Gothic, in which things like this happen:

Damn, Mrs. Langdon! Mrs. Langdon--Alison--is the sensitive and sickly wife of Major Langdon, who is having an affair with the wife of his superior officer, Captain Penderton. Leonora Penderton (hey--the same name as in The Good Soldier) is oversexed and frustrated by her marriage to the cold, aloof Captain, who seems mostly indifferent to his wife's affair. Into this volatile group, McCullers adds a fifth--a private named Williams who sneaks into Mrs. Pendleton's room every night to watch her sleep, in the nude.

Williams is something of an enigma--he rarely speaks, and has no friends or close associates. McCullers depicts him as a "natural," an idiot more at home in the woods than in the order of the barracks. The Captain obsesses over Williams, whose inscrutability is both threatening and mysterious. One scholar called Reflections in a Golden Eye one of the great "gay novels," and I admit that I missed the latent homosexuality suggested by the Captain's obsession. What was clear was the fine line between loving and loathing; the Captain's boiling hatred for Pvt. Williams is closer to real love than anything else in the novel, except perhaps for the relationship between Alison Langdon and her flamboyant servant Anacleto.

McCullers is one of the great novelists of the outsider, the marginalized figure. Even when she gives us a character with great status and power, like the Captain, she manages to find the deep secret within that puts him at the margins. She has the same kind of sympathy for Alison Langdon in her sickbed, and even the bitterly objectified and lonely Mrs. Penderton. The novel's most vivid and realized character, Anacleto, is an outsider twice over: a servant and a foreigner, clinging desperately and slavishly to Mrs. Langdon. Yet, he professes the kind of bravado and eccentricity that only a marginalized figure can; he's made in the mold of the deaf hedonist Antonapoulos from The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. McCullers' contempt, on the other hand, is saved for figures like Major Langdon, whose banality and conformity are far greater crimes than his infidelity.

As a closeted homosexual--if that's the best term for him--the Captain is shoved to the margins even of his own consciousness until that image comes to him, "distorted" and "doll-like." Private Williams, so far outside the realm of human activity that not even McCullers seems to understand or comprehend him, threatens the teetering social stability of these four even without their knowledge. It's no surprise when the novel, which hums with barely suppressed menace, erupts finally into grand violence. McCullers wrote in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter that "violence is the most precious flower of poverty"; but she was too often aware of the many ways, poverty besides, people are forced into invisibility and indignity.

'Why, you put it exactly right,' the Major said. 'Don't you agree with me?'

'No,' said the Captain, after a short pause. With gruesome vividness the Captain suddenly looked into his soul and saw himself. For once he did not see himself as others saw him; there came to him a distorted doll-like image, mean of countenance and grotesque in form. The Captain dwelt on this vision without compassion. He accepted it with neither alteration nor excuse.

The comparison I reached for immediately while reading Carson McCullers' Reflections in a Golden Eye is the "four-square house" of The Good Soldier, which comes tumbling down when John Dowell realizes that his wife and best friend have been carrying on an affair for years. But the "four-square house" of Reflections in a Golden Eye is rotten and termite-ridden to the core: its four pillars--two officers and their wives on a Southern army base during peacetime--already aware of the affair going on among them, and seething with loathing. McCullers transforms Edwardian reserve and gentility into Southern Gothic, in which things like this happen:

They had been sitting like this late one night when suddenly Mrs. Langdon, who had a high temperature, left the room and ran over to her own house. The Major did not follow her immediately, as he was comfortably stupefied with whiskey. Then later Anacleto, the Langdons' Filipino servant, rushed wailing into the room with such a wild-eyed face that they followed him without a word. They found Mrs. Langdon unconscious and she had cut off the tender nipples of her breasts with the garden shears.

Damn, Mrs. Langdon! Mrs. Langdon--Alison--is the sensitive and sickly wife of Major Langdon, who is having an affair with the wife of his superior officer, Captain Penderton. Leonora Penderton (hey--the same name as in The Good Soldier) is oversexed and frustrated by her marriage to the cold, aloof Captain, who seems mostly indifferent to his wife's affair. Into this volatile group, McCullers adds a fifth--a private named Williams who sneaks into Mrs. Pendleton's room every night to watch her sleep, in the nude.

Williams is something of an enigma--he rarely speaks, and has no friends or close associates. McCullers depicts him as a "natural," an idiot more at home in the woods than in the order of the barracks. The Captain obsesses over Williams, whose inscrutability is both threatening and mysterious. One scholar called Reflections in a Golden Eye one of the great "gay novels," and I admit that I missed the latent homosexuality suggested by the Captain's obsession. What was clear was the fine line between loving and loathing; the Captain's boiling hatred for Pvt. Williams is closer to real love than anything else in the novel, except perhaps for the relationship between Alison Langdon and her flamboyant servant Anacleto.

McCullers is one of the great novelists of the outsider, the marginalized figure. Even when she gives us a character with great status and power, like the Captain, she manages to find the deep secret within that puts him at the margins. She has the same kind of sympathy for Alison Langdon in her sickbed, and even the bitterly objectified and lonely Mrs. Penderton. The novel's most vivid and realized character, Anacleto, is an outsider twice over: a servant and a foreigner, clinging desperately and slavishly to Mrs. Langdon. Yet, he professes the kind of bravado and eccentricity that only a marginalized figure can; he's made in the mold of the deaf hedonist Antonapoulos from The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. McCullers' contempt, on the other hand, is saved for figures like Major Langdon, whose banality and conformity are far greater crimes than his infidelity.

As a closeted homosexual--if that's the best term for him--the Captain is shoved to the margins even of his own consciousness until that image comes to him, "distorted" and "doll-like." Private Williams, so far outside the realm of human activity that not even McCullers seems to understand or comprehend him, threatens the teetering social stability of these four even without their knowledge. It's no surprise when the novel, which hums with barely suppressed menace, erupts finally into grand violence. McCullers wrote in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter that "violence is the most precious flower of poverty"; but she was too often aware of the many ways, poverty besides, people are forced into invisibility and indignity.

Sunday, December 20, 2015

Eileen by Otessa Moshfegh

It's important to keep in mind, given what I'm about to relay, which is everything I remember from that evening, that I had truly never had a real friend before. Growing up I'd only had Joanie, who disliked me, and a girlfriend or two here and there in grade school, usually the other class reject. I remember a girl with braces on her legs in junior high, and an obese girl in high school who barely spoke. There was an Oriental girl whose parents owned the one Chinese restaurant in X-ville, but even she discarded me when she made cheerleading squad. Those were not real friends. Believing that a friend is someone who loves you, and that love is the willingness to do anything, sacrifice anything for the other's happiness, left me with an impossible ideal, until Rebecca. I held the phone close to my heart, caught my breath. I could have squealed with delight. If you've been in love, you know this kind of exquisite anticipation, this ecstasy. I was on the brink of something, and I could feel it.

It's important to keep in mind, given what I'm about to relay, which is everything I remember from that evening, that I had truly never had a real friend before. Growing up I'd only had Joanie, who disliked me, and a girlfriend or two here and there in grade school, usually the other class reject. I remember a girl with braces on her legs in junior high, and an obese girl in high school who barely spoke. There was an Oriental girl whose parents owned the one Chinese restaurant in X-ville, but even she discarded me when she made cheerleading squad. Those were not real friends. Believing that a friend is someone who loves you, and that love is the willingness to do anything, sacrifice anything for the other's happiness, left me with an impossible ideal, until Rebecca. I held the phone close to my heart, caught my breath. I could have squealed with delight. If you've been in love, you know this kind of exquisite anticipation, this ecstasy. I was on the brink of something, and I could feel it.Otessa Moshfegh's Eileen was a surprise, not because it was good, but because of how good it was. Moshfegh is a Paris Review favorite. According to her wikipedia page, she's published 6 stories since 2012; I think it's been four in the two years since I started subscribing (you can see in my Paris Review Review from last year, two of her stories made my best list). So, while I expected to enjoy her novel, I (for no reason I can discern) did not expect to love it. It was my favorite novel this year.

The novel is narrated by Eileen, reflecting back on 1964. Early into the novel we learn: (1) she did something that required her to leave her home town; (2) she was a very different person in 1964 than she is when she narrates the novel; (3) she was plain--at least viewed herself so; and (4) she cares for her alcoholic father, who is losing his sanity.

This conveys two things to the reader: that Eileen feels trapped by her situation and that something is about to dramatically change.

I can't describe how skillfully (and quickly) Moshfegh conveys this information. I also don't want to reveal to much because a lot of the pleasure of this novel is the slow unwrapping of Eileen's life, leading up to this event that both defines the novel and Eileen's life.

The precipitating change that begins the chain of events in the novel is the arrival of a new coworker, Rebecca. Rebecca is everything that Eileen is not: where Rebecca is attractive, Eileen is plain; where Rebecca is confident and assertive, Eileen is self-conscious and quiet. They become friends and the novel progresses from there.

Two characteristics of this novel made me enjoy it so much: First, Moshfegh's writing shines. It's engaging throughout, even if it feels like nothing is happening in the story. Second, Moshfegh writes about a topic that I often feel is under-represented in literature, what life is like under the cloud of poverty and mental illness.

Moshfegh is quite young (34), so I'm hoping this is the first of many more novels of this caliber.

And, because this was a good article about her, I'm linking to the Vanity Fair write-up of her, aptly titled, Don't Google Otessa Moshfegh: Read Her Debut Novel, Eileen, Instead.

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

Love's Labour's Lost by William Shakespeare

BEROWNE:

...From women's eyes this doctrine I derive.

They sparkle still the right Promethean fire;

They are the books, the arts, the academes,

That show, contain, and nourish all the world;

Else none at all in aught proves excellent,.

Then fools you were these women to forswear,

Or, keeping what is sworn, you will prove fools.

For wisdom's sake, a word that all men love,

Or for love's sake, a word that loves all men,

Or for men's sake, the authors of these women,

Or women's sake, by whom we men are men--

Let us once lose our oaths to find ourselves,

Or else we lose ourselves to keep our oaths.

Love's Labour's Lost promises us a love story, and delivers a bitter pill. The setup is right out of some Medieval rom-com: The King of Navarre and his retinue, Dumaine, Longaville, and Berowne, take an oath to forswear women for three years so they might devote themselves to serious study. Only Berowne sense that this is a bad idea, and predicts that they'll all break their oaths before long:

The predictable thing happens next: women arrive, in the form of the Princess of Aquitaine and her retinue, and the King and his men fall deeply in love, each with a different woman. Each man tries vainly to woo his love's object while keeping it hidden from the others. This leads to a very funny scene in which each male character enters reading aloud a love poem of his own devising, and then, when he hears the next one approaching, scuttles into hiding. Each poem is worse and worse, until finally there are three guys hiding, to various degrees of each others' awareness, listening to Longaville's shitty poem, which begins "On a day--alack the day!-- / Love, whose month is every may, / Spied a blossom passing fair / Playing in the wanton air."

Once they spend a little while shaking their fingers at each other, the menfolk put their heads together to try to woo the Princess and her maids. Though his prediction is proved correct, Berowne comes in for the worst criticism, because his beloved, Rosaline, is supposedly exceedingly ugly and "black," or dark-skinned. As the King says, "I'll find a fairer face not washed today." This echoes with the presence of the "dark lady" of the sonnets, who is equally ugly ("My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun"), equally crass and sordid, and yet whose attraction is--for Berowne as for the speaker of the sonnets--unavoidable.

Love in Love's Labour's Lost has all the dressing of poetry and courtly romance, but at its bottom, it's like Berowne's love for Rosaline: inexplicable, physical, almost bestial. Rosaline treats Berowne with bitter jabs, and he is helpless. The other women, sensing that the men's sincerity is questionable, play a trick on them by switching their masks. (Why are they wearing masks? Why not?) The men, as they suspect, cannot tell one from the other without their physical likenesses. The play which seemed, at the beginning, to set up a predictable course toward resolution, seems to suggest that the dynamics of human love and sex are irresolvable: men obsess, and women rebuff.

The play ends when the real world interrupts the childish play of love: a messenger comes to inform the Princess that her father has died. The King, like an entitled MRA, demands to be loved: "Now, at the latest minute of the hour / Give us your loves." The women impose harsh penitences in exchange, perhaps knowing that the men will not keep them: The King must spend a year as a hermit, and Berowne, healing the sick. Some sources suggest there is a lost sequel to the play--Love's Labour's Won--perhaps in which the King, Berowne, and all the rest complete their hairshirt requirements and win the ladies they sought to woo. But I doubt it.

...From women's eyes this doctrine I derive.

They sparkle still the right Promethean fire;

They are the books, the arts, the academes,

That show, contain, and nourish all the world;

Else none at all in aught proves excellent,.

Then fools you were these women to forswear,

Or, keeping what is sworn, you will prove fools.

For wisdom's sake, a word that all men love,

Or for love's sake, a word that loves all men,

Or for men's sake, the authors of these women,

Or women's sake, by whom we men are men--

Let us once lose our oaths to find ourselves,

Or else we lose ourselves to keep our oaths.

Love's Labour's Lost promises us a love story, and delivers a bitter pill. The setup is right out of some Medieval rom-com: The King of Navarre and his retinue, Dumaine, Longaville, and Berowne, take an oath to forswear women for three years so they might devote themselves to serious study. Only Berowne sense that this is a bad idea, and predicts that they'll all break their oaths before long:

Necessity will make us all forsworn

Three thousand times within this three years' space:

For every man with his affects is born,

Not by might mast'red, but by special grace.

If I break faith, this word shall speak for me,

I am forsworn "on mere necessity."

The predictable thing happens next: women arrive, in the form of the Princess of Aquitaine and her retinue, and the King and his men fall deeply in love, each with a different woman. Each man tries vainly to woo his love's object while keeping it hidden from the others. This leads to a very funny scene in which each male character enters reading aloud a love poem of his own devising, and then, when he hears the next one approaching, scuttles into hiding. Each poem is worse and worse, until finally there are three guys hiding, to various degrees of each others' awareness, listening to Longaville's shitty poem, which begins "On a day--alack the day!-- / Love, whose month is every may, / Spied a blossom passing fair / Playing in the wanton air."

Once they spend a little while shaking their fingers at each other, the menfolk put their heads together to try to woo the Princess and her maids. Though his prediction is proved correct, Berowne comes in for the worst criticism, because his beloved, Rosaline, is supposedly exceedingly ugly and "black," or dark-skinned. As the King says, "I'll find a fairer face not washed today." This echoes with the presence of the "dark lady" of the sonnets, who is equally ugly ("My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun"), equally crass and sordid, and yet whose attraction is--for Berowne as for the speaker of the sonnets--unavoidable.

Love in Love's Labour's Lost has all the dressing of poetry and courtly romance, but at its bottom, it's like Berowne's love for Rosaline: inexplicable, physical, almost bestial. Rosaline treats Berowne with bitter jabs, and he is helpless. The other women, sensing that the men's sincerity is questionable, play a trick on them by switching their masks. (Why are they wearing masks? Why not?) The men, as they suspect, cannot tell one from the other without their physical likenesses. The play which seemed, at the beginning, to set up a predictable course toward resolution, seems to suggest that the dynamics of human love and sex are irresolvable: men obsess, and women rebuff.

The play ends when the real world interrupts the childish play of love: a messenger comes to inform the Princess that her father has died. The King, like an entitled MRA, demands to be loved: "Now, at the latest minute of the hour / Give us your loves." The women impose harsh penitences in exchange, perhaps knowing that the men will not keep them: The King must spend a year as a hermit, and Berowne, healing the sick. Some sources suggest there is a lost sequel to the play--Love's Labour's Won--perhaps in which the King, Berowne, and all the rest complete their hairshirt requirements and win the ladies they sought to woo. But I doubt it.

Labels:

comedy,

Love's Labour's Lost,

william shakespeare

Monday, December 14, 2015

The Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway

So now it was all over, he thought. So now he would never have a chance to finish it. So this was the way it ended in a bickering over a drink. Since the gangrene started in his right leg he had no pain and with the pain the horror had gone and all he felt now was a great tiredness and anger that this was the end of it. For this, that now was coming, he had very little curiosity. For years it had obsessed him; but now it meant nothing in itself. It was strange how easy being tired enough made it.

Now he would never write the things that he had saved to write until he knew well enough to write them well. Well, he would not have to fail at trying to write them either. Maybe you could never write them, and that was why you put them off and delayed the tarting. Well, he would never know, now.

Hemingway is one of those blank spots for me--I read The Sun Also Rises eons ago, in high school, and nothing ever sense. I don't know why. Perhaps it seemed like the one notable thing about Hemingway, the extreme terseness of his style, was easy enough to appreciate without ever actually reading his work. I get the famous iceberg metaphor--most of what happens in a story is beneath the surface.

But even still, appreciation is not reading, and the stories of The Snows of Kilimanjaro really do conceal remarkable deaths. "A Clean, Well-Lighted Place" is only a couple of slim pages, but the story it tells is tremendous: two waiters gossip about a deaf patron who, they understand, recently tried to kill himself. The younger waiter wants to go home; the older one knows what the cafe being open might mean to the deaf patron. It is a "clean, well-lighted place," and a bastion against existential terror:

Turning off the electric night he continued the conversation with himself. It is the light of course but it is necessary that the place be clean and pleasant. You do not want music. Certainly you do not want music. Nor can you stand before a bar with dignity although that is all that is provided for these hours. What did he fear? It was not fear or dread. It was nothing that he knew too well. It was all a nothing and man was nothing too. It was only that and light was all it needed and a certain cleanness and order. Some lived in it and never felt it but he knew it all was nada y pues nada y nada y nada y pues nada. Our nada who art in nada, nada be thy name thy kingdom nada thy will be nada in nada as it is in nada. Give us this nada our daily nada and nada us our nada as we nada our nadas and nada us not into nada but deliver us from nada; pues nada. Hail nothing full of nothing, nothing is with thee. He smiled and stood before a bar with a shining steam pressure coffee machine.

Like the best writers, Hemingway captures a familiar feeling with words we didn't know were available. Someone who can't sympathize with that feeling I do not understand, and suspect they must not read a lot of books.

Elsewhere, Hemingway uses this style to a different effect. I especially enjoyed the story "A Day's Wait," about a boy who has a fever of 102. He becomes silent and contemplative, until, at the story's end, he asks his father when he will die. His French boarding school friends, you see, have told him that you can't survive a fever past 44 degrees--Celsius. The reveal is funny, but the boy's steely reserve is, like the quiet resignation of the gangrenous vacationer in the title story (quoted above), subtly profound. The concept is clever, but there is no sense of gimmickry.

I also found that Hemingway's reputation for unchecked machismo was overstated. It seemed to me, from these stories, that Hemingway was as familiar with the hollowness of masculine posturing as much as anyone--just look at the final story, "The Short and Happy Life of Francis Macomber," about a stuffed-shirt so embarrassed by his running from a lion while hunting in Africa, that he gets himself killed by a water buffalo. That outcome is not so surprising, but Hemingway, in his staccato way, fills the story with other kinds of dread: the dread that Macomber might be killed by his wife, who is disgusted by his cowardice, or by their guide, who sleep with Macomber's wife--or that he might kill them. When it ends the way you thought it might, you find yourself surprised anyway, and a little sad about the inevitability of self-destruction.

Saturday, December 12, 2015

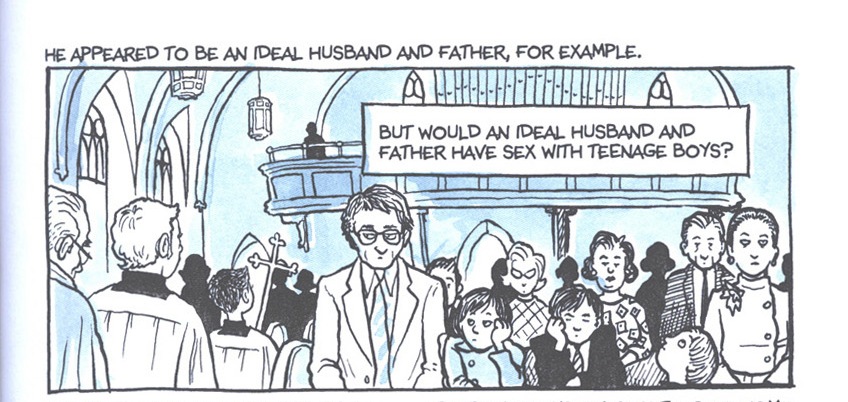

Fun Home by Alison Bechdel

Alison Bechdel's memoir Fun Home must be one of the most lauded graphic novels of all time, and with good reason: it's incredibly complex and incredibly moving. I resisted the urge to add "for a graphic novel" to the end of that last sentence, because I think that it stands on its own as a piece of great literature, rather than relative to the quality of graphic novels in general. In fact, Fun Home seems vital in a way that very few novels from the last ten years really can claim.

Bechdel's memoir describes her experience coming out as a lesbian, while at the same time learning that her father had been having affairs with men for decades. He dies, hit by a car, shortly after these revelations. Bechdel wonders in Fun Home if he stepped in front of the car intentionally, but there's no way to be sure, and she must grapple with the pain of that uncertainty. Either way, his death is the catalyst for the novel, which seeks to do the work of reconciliation and understanding that her father's absence made impossible to do face-to-face.

One thing that surprised me about Fun Home was how literary it was. Bechdel's father was an English teacher (in addition to running the funeral home which gives the novel its title), and Bechdel turns to numerous literary sources in search of a narrative that will make her relationship with her father meaningful. Camus, Fitzgerald, Proust, Joyce, and Wilde all make appearances. But these narratives never seem to quite be enough to help Bechdel pin her father down in a way that provides consolation or closure. The choice to write the memoir as a graphic novel seems significant in this way, as an attempt to break with the insufficient narratives of the past and make something new--without abandoning or dismissing the authors of the past.

That's a really academic way of looking at it, I guess. But essentially, Fun Home is a very human, very moving story. Bechdel's relationship with her parents is very troubled--she describes her father as cold and aloof for most of her life--and as soon as it looks like they might have something to bring them together, he dies. As beautiful a story as it is, there's a fundamental and ineradicable sadness about the impossibility of recovering that lost opportunity.

Labels:

Alison Bechdel,

Fun Home,

Graphic novel,

homosexuality

Thursday, December 10, 2015

Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges

The composition of vast books is a laborious and impoverishing extravagance. To go on for five hundred pages developing an idea whose perfect oral exposition is possible in a few minutes! A better course of procedure is to pretend that these books already exist, and then to offer a resume, a commentary. Thus proceeded Carlyle in Sartor Resartus. Thus Butler in The Fair Haven. these are works which suffer the imperfection of being themselves books, and of being no less tautological than the others. More reasonable, more inept, more indolent, I have preferred to write notes upon imaginary books.

I recently moved. During that ordeal, almost all of my books were packed up, and I was forced for a whole month to raid the book room at the school where I teach for stuff to read. That was fortuitous, actually, otherwise I would not yet have gotten around to reading Borges' short story collection Ficciones, or Hemingway's The Snows of Kilimanjaro, or Alison Bechdel's terrific graphic memoir Fun Home. But Borges' stories, stuffed as they are with labyrinths, and stories nested within stories like boxes within boxes, actually seemed reminiscent of my apartment while I was packing.

So I lived in a "Garden of Forking Paths" for a little while--but in a less tongue-in-cheek way, the famous story of that title did make me think about the way I ended up here, at this moment, moving to this place with this person, when it might so easily have been otherwise. "The Garden of Forking Paths" is about a Chinese spy for the German government, living in Britain, who murders a renowned Sinologist because the man's name, Albert, will reveal the location of a similarly named artillery park when his name is published in the newspaper. Albert is familiar with the legend of the narrator's grandfather, who vanished leaving his two goals unfinished--to write an intricate novel, and to create an equally intricate labyrinth. The book and the labyrinth, Albert tells the narrator, are the same; the book sought to encompass all of the possible paths that fork in time, branching off at the junction of each decision. And yet it is not a labyrinth we can navigate or escape, for as the narrator says:

Borges' stories are all like that, tangled intellectual knots on the subjects of time, fiction, and imagination. Many of them are only brief commentaries on longer works that never existed, playing with the illusory border between fiction and the real. In "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote," he writes a fictional memoir about a fictional author whose masterwork is a line-for-line reproduction of Don Quixote, which surpasses the original because the 300 intervening years have made its allusions richer. In "The Library of Babel," he describes a universe which is comprised of a massive library, where all books are composed of random letters and punctuation. Those born into this universe reason that all information must be somewhere in the library--each person's biography, predictions of the future, even the full index of the library's own contents--and go mad searching for sense among the nonsense. Their predicament sounds grotesque--but is it different from our own experience, searching for patterns in a random universe to create meaning?

I was surprised how philosophically dense most of these stories are. In "Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius," he describes a conspiracy to create an imaginary country, Tlon, which becomes a discussion of metaphysics and subjective idealism, the philosophy which maintains only minds and ideas exist. (At the end of the story, Borges suggests that the real world is becoming, or merging with, the imaginary Tlon!) The influence of Borges is easy to spot, but it's hard to name a writer with the same kind of intellectual heft, or the compelling brevity.

I recently moved. During that ordeal, almost all of my books were packed up, and I was forced for a whole month to raid the book room at the school where I teach for stuff to read. That was fortuitous, actually, otherwise I would not yet have gotten around to reading Borges' short story collection Ficciones, or Hemingway's The Snows of Kilimanjaro, or Alison Bechdel's terrific graphic memoir Fun Home. But Borges' stories, stuffed as they are with labyrinths, and stories nested within stories like boxes within boxes, actually seemed reminiscent of my apartment while I was packing.