I understood immediately the thrill of seeing oneself in print. It provides some sort of primal verification: you are in print; therefore you exist. Who knows what this urge is all about, to appear somewhere outside yourself, instead of feeling stuck inside your muddled but stroboscopic mind, peering out like a little undersea animal--a spiny blenny, for instance--from inside your tiny cave?

"Do it every day for a while," my father kept saying. Do it as you would do scales on the piano. Do it by prearrangement with yourself. Do it as a debt of honor. And make a commitment to finishing things."

I heard a preacher say recently that hope is a revolutionary patience; let me add that so is being a writer. Hope begins in the dark, the stubborn hope that if you just show up and try to do the right thing, the dawn will come. You wait and watch and work: you don't give up.

The very first thing I tell my new students on the first day of a workshop is that good writing is about telling the truth.

E. L. Doctorow once said that "writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way."

Writing can be a pretty desperate endeavor, because it is about some of our deepest needs: our need to be visible, to be heard, our need to make sense of our lives, to wake up and grow and belong. It is ino wonder if we sometimes tend to take ourselves perhaps a bit too seriously.

The first draft is the child's draft, where you let it all pour out and then let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later. You just let this childlike part of you channel whatever voices and visions come through and onto the page. If one of the characters wants to say, "Well, so what, Mr. Poopy Pants?" you let her.

Writing a first draft is very much like watching a Polaroid develop. You can't--and in fact, you're not supposed to--know exactly what the picture is going to look like until it has finished developing. First you just point at what has your attention and take the picture.

But something must be at stake or else you will have no tension and your readers will not turn the pages. Think of a hockey player--there had better be a puck out there on the ice, or he is going to look pretty ridiculous.

You get your intuition back when you make space for it, when you stop the chattering of the rational mind. The rational mind doesn't nourish you. You assume that it gives you the truth, because the rational mind is the golden calf that this culture worships, but this is not true. Rationality squeezes out much that is rich and juicy and fascinating.

...you don't always have to chop with the sword of truth. You can point with it, too.

Showing posts with label Bird by Bird. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Bird by Bird. Show all posts

Wednesday, September 4, 2019

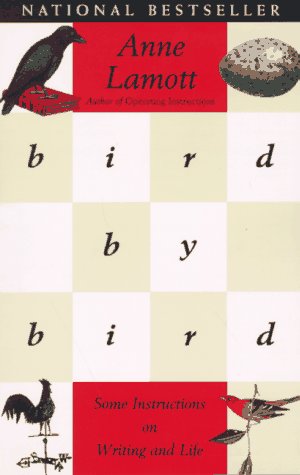

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

Labels:

anne lamott,

Bird by Bird,

writing

Saturday, September 9, 2017

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

I heard a preacher say recently that hope is a revolutionary patience; let me add that so is being a writer. Hope begins in the dark, the stubborn hope that if you just show up and try to do the right thing, the dawn will come. You wait and watch and work: you don't give up.

I can't name any of Anne Lamott's books; I think a lot of people who know Bird by Bird can't. There's a special irony to that, that an author's book on writing could so completely eclipse the fiction that they have written. Budding writers turn to this book again and again despite having no real proof that Lamott is a worthy person to be giving advice. What could be the reason for it?

It certainly doesn't contain the most practical advice. There are few exercises, and what there are of concrete suggestions are idiosyncratic. Don't write on Mondays, she says. Start by just writing about your childhood. The magic of Bird by Bird, I think, is how perfectly it captures the neurosis and trauma that visits writers. Lamott understands neurosis and trauma pretty well, but especially that kind that visits writers. She writes about it with a dark but assuring sense of humor, managing somehow to provide optimism while reminding the reader that what they write will probably never be successful. Lamott's powerful, sardonic voice gives the impression of sympathy; there's someone out there who understands what it's like to want to write and have it not come easy.

Ultimately, Bird by Bird makes good on its subtitle: "Some instructions for writing and life." The writing advice is good, if not always pragmatic, but the most powerful parts are when Lamott talks about the death of her witty, intelligent father from brain cancer, or the death of her close friend Pammy, also from cancer. She talks about writing their stories as a kind of gift to give to them and it doesn't seem at all maudlin. She's able to get to the heart, I think, of why writing is so appealing: its ability to transcend, or feel as if it transcends, the narrowness of the world, and even the banal inevitability of dying. And yet the book is so lighthearted.

I'm teaching creative writing--four sections of it, my gosh--for the first time this year. I don't know what I'm doing. I returned to Bird by Bird for some advice that might be useful to my own budding writers, but I also found a lot of good advice about dealing with not knowing what you're doing in general. Most of writing is just showing up and doing it, she says. Hopefully that's true for teaching writing, too.

I can't name any of Anne Lamott's books; I think a lot of people who know Bird by Bird can't. There's a special irony to that, that an author's book on writing could so completely eclipse the fiction that they have written. Budding writers turn to this book again and again despite having no real proof that Lamott is a worthy person to be giving advice. What could be the reason for it?

It certainly doesn't contain the most practical advice. There are few exercises, and what there are of concrete suggestions are idiosyncratic. Don't write on Mondays, she says. Start by just writing about your childhood. The magic of Bird by Bird, I think, is how perfectly it captures the neurosis and trauma that visits writers. Lamott understands neurosis and trauma pretty well, but especially that kind that visits writers. She writes about it with a dark but assuring sense of humor, managing somehow to provide optimism while reminding the reader that what they write will probably never be successful. Lamott's powerful, sardonic voice gives the impression of sympathy; there's someone out there who understands what it's like to want to write and have it not come easy.

Ultimately, Bird by Bird makes good on its subtitle: "Some instructions for writing and life." The writing advice is good, if not always pragmatic, but the most powerful parts are when Lamott talks about the death of her witty, intelligent father from brain cancer, or the death of her close friend Pammy, also from cancer. She talks about writing their stories as a kind of gift to give to them and it doesn't seem at all maudlin. She's able to get to the heart, I think, of why writing is so appealing: its ability to transcend, or feel as if it transcends, the narrowness of the world, and even the banal inevitability of dying. And yet the book is so lighthearted.

I'm teaching creative writing--four sections of it, my gosh--for the first time this year. I don't know what I'm doing. I returned to Bird by Bird for some advice that might be useful to my own budding writers, but I also found a lot of good advice about dealing with not knowing what you're doing in general. Most of writing is just showing up and doing it, she says. Hopefully that's true for teaching writing, too.

Labels:

anne lamott,

Bird by Bird,

writing

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)