I understood immediately the thrill of seeing oneself in print. It provides some sort of primal verification: you are in print; therefore you exist. Who knows what this urge is all about, to appear somewhere outside yourself, instead of feeling stuck inside your muddled but stroboscopic mind, peering out like a little undersea animal--a spiny blenny, for instance--from inside your tiny cave?

"Do it every day for a while," my father kept saying. Do it as you would do scales on the piano. Do it by prearrangement with yourself. Do it as a debt of honor. And make a commitment to finishing things."

I heard a preacher say recently that hope is a revolutionary patience; let me add that so is being a writer. Hope begins in the dark, the stubborn hope that if you just show up and try to do the right thing, the dawn will come. You wait and watch and work: you don't give up.

The very first thing I tell my new students on the first day of a workshop is that good writing is about telling the truth.

E. L. Doctorow once said that "writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way."

Writing can be a pretty desperate endeavor, because it is about some of our deepest needs: our need to be visible, to be heard, our need to make sense of our lives, to wake up and grow and belong. It is ino wonder if we sometimes tend to take ourselves perhaps a bit too seriously.

The first draft is the child's draft, where you let it all pour out and then let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later. You just let this childlike part of you channel whatever voices and visions come through and onto the page. If one of the characters wants to say, "Well, so what, Mr. Poopy Pants?" you let her.

Writing a first draft is very much like watching a Polaroid develop. You can't--and in fact, you're not supposed to--know exactly what the picture is going to look like until it has finished developing. First you just point at what has your attention and take the picture.

But something must be at stake or else you will have no tension and your readers will not turn the pages. Think of a hockey player--there had better be a puck out there on the ice, or he is going to look pretty ridiculous.

You get your intuition back when you make space for it, when you stop the chattering of the rational mind. The rational mind doesn't nourish you. You assume that it gives you the truth, because the rational mind is the golden calf that this culture worships, but this is not true. Rationality squeezes out much that is rich and juicy and fascinating.

...you don't always have to chop with the sword of truth. You can point with it, too.

Wednesday, September 4, 2019

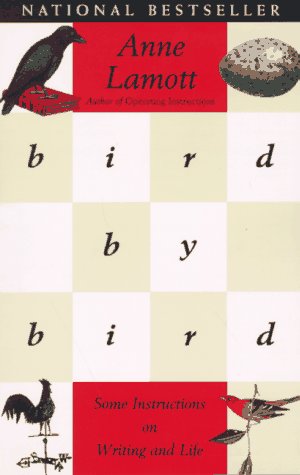

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

Labels:

anne lamott,

Bird by Bird,

writing

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment