Thank you, dear Commandant, for the notes that you and the commissar have given me on my confession. You have asked me what I mean when I say "we" or "us," as in those moments when I identify with the southern soldiers and evacuees on whom I was sent to spy. Should I not refer to those people, my enemies, as "them"? I confess that after having spent almost my whole life in their company I cannot help but sympathize with them, as I do with many others. My weakness for sympathizing with others has much to do with my status as a bastard, which is not to say that being a bastard naturally predisposes one to sympathy. Many bastards behave like bastards, and I credit my gentle mother with teaching me the idea that blurring the lines between us and them can be a worthy behavior. After all, if she had not blurred the lines between maid and priest, or allowed them to be blurred, I would not exist.

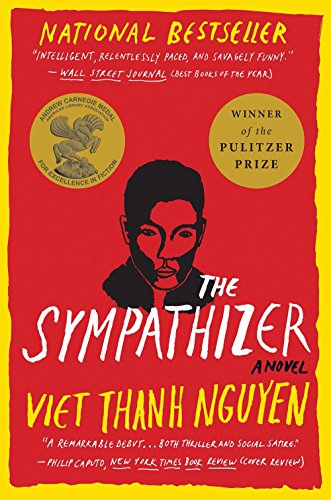

I wanted to read Viet Thanh Nguyen's The Sympathizer as a complement to Tree of Smoke. Denis Johnson's novel is about the bewildered American in Vietnam, and Nguyen's is about the bewildered Vietnamese in America: specifically, an unnamed narrator working for an exiled South Vietnamese general in Los Angeles after the fall of Saigon. The narrator has a secret, though: he's really a committed communist, sending reports back to his North Vietnamese handlers. His unique position allows him to sympathize with both sides of the conflict, his northern colleagues and his southern friends. The dominant imagery in the novel all points to a split identity: Northern vs. Southern Vietnam, the East and the West, his French father and his Vietnamese mother.

Like Tree of Smoke, The Sympathizer makes explicit references to Graham Greene. The highly educated narrator, we learn, wrote his masters' thesis on the novelist's depiction of Vietnam; he's an expert in the way that the Western eye looks at his home country. It mimics Greene in its reliance on intrigue and spy stuff, as well as its interest in the psyche of a double agent. Its moral questions are very Greene-like: How can the murder of a communist by a communist be considered the right thing? If it helps the narrator keep his cover, is that enough?

But The Sympathizer is at its best when it's in high satire mode, like when the narrator reminisces about how he learned to masturbate with his mother's fresh squid as a child, or when a pompous Orientalist professor encourages him to write down and compare his "Oriental" and "Occidental" qualities. (There's a lot of satisfying tension in the way Nguyen mocks the reductive nature of binaries, while acknowledging that they have a real impact on the narrator's psyche.) A big chunk of the book is taken up the narrator's experience advising a movie production about the Vietnam War in the Philippines that is a clear analogue of Apocalypse Now. He wants to chip away at such propaganda from the inside, making a space for Vietnamese actors and tinkering with the script. He advises the director, called only the Auteur, that Vietnamese people don't go AIIIEEEE!!! when they scream, but AIEY-AAHHH!!! His efforts amount to very little; the Vietnamese Potemkin village mocks the absence of his home, and he ends up, in characteristic fashion, becoming part of the very machine he wants to work against.

It's not The Sympathizer's fault, but I found myself missing Johnson's anarchic prose style. The language in The Sympathizer is very staid and prim. It's a way for the narrator to exert control over the warring factions of his mind, and to assert an essential dignity in the face of Americans who would reduce him to ethnic stereotypes. Sometimes it works toward satirical ends, as when he tells us, "Perhaps I went too far when I invited him to perform fellatio on me," or when he calls sex the "oldest dialectic," but at other times it feels stilted or forced.

Ultimately, The Sympathizer is a book I respected more than enjoyed. I liked it most when it was at its silliest, and less when it was in its more serious mode. I thought that the end, which details the narrator's capture and torture by his own northern colleagues and is clearly inspired by the end of 1984, to be unfortunately muddled when the narrative needed clarity most. But the larger tragedy of the book is inescapable: the narrator has been exactly what his colleagues wanted, a convincing spy, but his strength becomes his weakness. His sympathy must be cleansed out of him; there is no room in the world for someone who can see both sides.

No comments:

Post a Comment