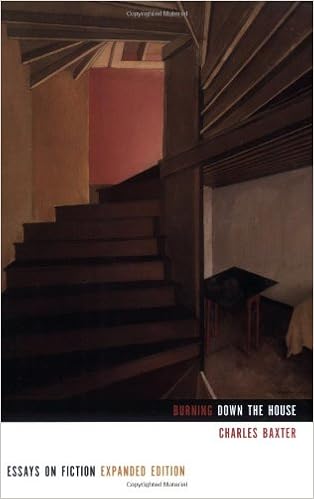

"There are a number of wild claims here," Charles Baxter says in the introduction to his collection of essays, Burning Down the House, "an occasional manic swing toward the large statements." They are "meant to be playful rather than ponderous," but they are meant to perform the title action of dismantling the understanding we have of literature, the kind that is so ubiquitous that we barely notice it. You can see that kind of fence-swinging in his statement on poets, whose lives are rarely the kind you would "wish upon your children." That seems a little more Ezra Pound than Mary Oliver to me, but it serves as a preface to a thoughtful essay that examines the way that narrative fiction, like poetry, has its own kind of rhyming, and like poetry it suffers if the rhyming is too clunky or exact.

I don't know if Baxter succeeds in burning down anything, but I did come away from these essays feeling like I had noticed things about modern literature that were beyond my sight. "Against Epiphanies," for example, shows just how reliant we have become on sudden realizations, though they are only rarely to be found in life as it's really lived. When we begin to expect epiphanies from our fiction we create false expectations and a kind of staleness: "The old insight train just comes chugging into the station, time after time."

Several essays deal with the ways in which our narratives have become deprived of meaningful action, especially wrong or villainous action. In one, he connects this symptom to the passive Nixonese that is still the lingua franca of the political class: "Mistakes were made." "In an atmosphere of constant moral judgment," he writes, "characters are not often permitted to make interesting and intelligent mistakes and then to acknowledge them." Instead, we write fiction as therapy, in which characters unearth traumas that explain their actions but rob them of agency. "The injury is the meaning" in these agentless narratives, "although it is, itself, opaque." A Thousand Little Acres receives special opprobrium. In another essay, he links our distaste for melodrama--defined as something like the work of evil for its own sake against innocence--to the cultural disappearance of the devil:

Satan as a figure is dead, but evil continues, without, however, someone to answer for it. Evil is more evil than ever, even when we have no name for it and no Satanic figure to blame for it. We still have melodrama, however: the honorable narrative house of horror and the unforgivable.

I got this book because it was on a list, somewhere, of great books about writing. It is a great book about fiction, but I'm not sure it's a great book about writing. Really interesting writing books are often full, I have found, of useless advice. Not necessarily wrong, but not useful, at least not for my purposes:

As an undergraduate I was taught that when a writer starts a story, s/he must begin with a character, an active, preferably vivid, ideally sympathetic, character. It takes a bit of time to see that stories don't in fact begin with characters, not from here, at least, not from behind this keyboard. They begin with words, one word after another.

Although I would never tell a student to make a character sympathetic (much better to make them a nasty little shit), I do tell them to begin with character. And it's not because that's what good fiction always does--though I don't think it's true in any meaningful sense that it begins with words, one word after another, either--but because it disorients students from the way they see writing as about plot and action. Baxter wants to return action, and moral agency, to the center of fiction, but students have trouble when it comes to retrofitting characters to the kinds of stories they want to tell. If they want to write a story about an alcoholic dad (and they do), they will fit the character into that box, but if you have them think about what kind of person the dad is and what he wants and how that manifests in action, the story begins to look more like life. And in fact, I think teenagers are especially susceptible to the kind of void in agency that he critiques, partially because they have yet to develop a critical eye toward the kind of narratives they consume, and partially because their own lives are pretty free of meaningful agency.

Anyway. The essays here are thoughtful and clever, wry and colloquial in style, and filled with illustrations from Flannery O'Connor and Marilynne Robinson and Donald Barthelme and Sylvia Townsend Warner in a way that seems mostly borne out of love. (Not poor old Jane Smiley, though.) It gave me a lot to think about in my own writing, even if it didn't make me want to burn down the whole house.

No comments:

Post a Comment