Sister Agnes: There is no inch in the world without God. I breathe him, the birds of heaven breathe him, fish breathe him in the deepest waters where air cannot be seen or felt, but where air is. Man walks and dies; he breathes and becomes breath--as if a dolphin flying skyward were snatched forever into a net of air.

It is the Mother Superior's turn to speak. Sipping a glass of water, she sighs, "Sister Agnes, show me your ass."

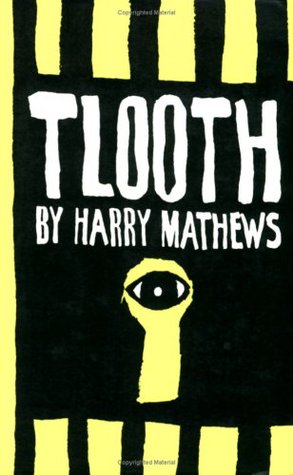

Harry Mathews' Tlooth begins in a Siberian prison camp, where the prisoners are split into "sects" based on their religious beliefs. The Defective Baptists are playing the Fideists in baseball. The narrator has secretly packed a baseball with dynamite, and is planning to use it to kill Evelyn Roak, the surgeon who accidentally, or perhaps maliciously, removed the narrator's middle two fingers, ruining a promising career as a violinist. The plan doesn't work, thanks to a wild pitch, but when Roak is released from prison, it sets off a long chase across several continents.

Like The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium, Tlooth is full of gratuitous wordplay and puzzles of all sorts. But it's not always easy to tell what is and what isn't a puzzle, something to be figured out. When the narrator's traveling band is accosted in the Eurasian steppes by a group of nomad kings who offer a kind of repetitive poem-song, is that a puzzle? Is there a solution lurking in there somewhere that makes the whole thing satisfying on a level beyond the exotic strangeness of the scene? Or is it all like the poem traced on the labyrinth of their animal-shaped derby racer (another tradition of the prison camp, like the baseball games), which leads to the same spot where it began? There's a Nabokov-like suggestion running throughout the book that the puzzles, whatever they are, are to no purpose, and that deciphering the wordplay is a kind of fool's game.

In Odradek, I didn't mind the wordplay because, even when it seemed self-referential or circuitous, it was grounded by the relationship between the two main characters, who have overcome their linguistic differences to fall in love, or so they think. The revenge narrative of Tlooth seems to offer something similar, but less successfully. Mostly, it seems to offer a set of open-ended questions. What am I supposed to make of the long digression in which the narrator pens a scene for a pornographic "blue movie?" (I did like the bit of dialogue I quoted up at top, though.) What's the point of giving most of the characters ambiguously gendered names, and only revealing that the narrator--and Roak--are female toward the very end of the novel? It certainly toys cleverly with my sense of character, and chastises me for coding the revenge plot as male. But I couldn't shake a feeling of boredom, a sense that the answer to these questions is that there is no answer. I admit that I didn't always "get" Tlooth, but neither am I sure what there is to get.

Along the way, at least, Tlooth offers up a bunch of fun little vignettes. The title comes from a moment when the protagonist sticks her foot in a prophetic bog, which tells her fortune in a gas bubble: "Tlooth." Her prison training as a dentist is what allows the protagonist to finally get her revenge. But it's a reference also to the "truth," something which the novel is not very forthcoming with, and when it does offer something like it, it's slightly off, put through the wringer of wordplay: Tlooth.

No comments:

Post a Comment