The surprise of seeing me halted his hand between pan and face. Then tears of joy welled up.

"Oh Lor', I know it you call my name. Nobody don't callee me my name from cross de water but you. You always callee me Kossula, jus' lak I in de Affica soil!"

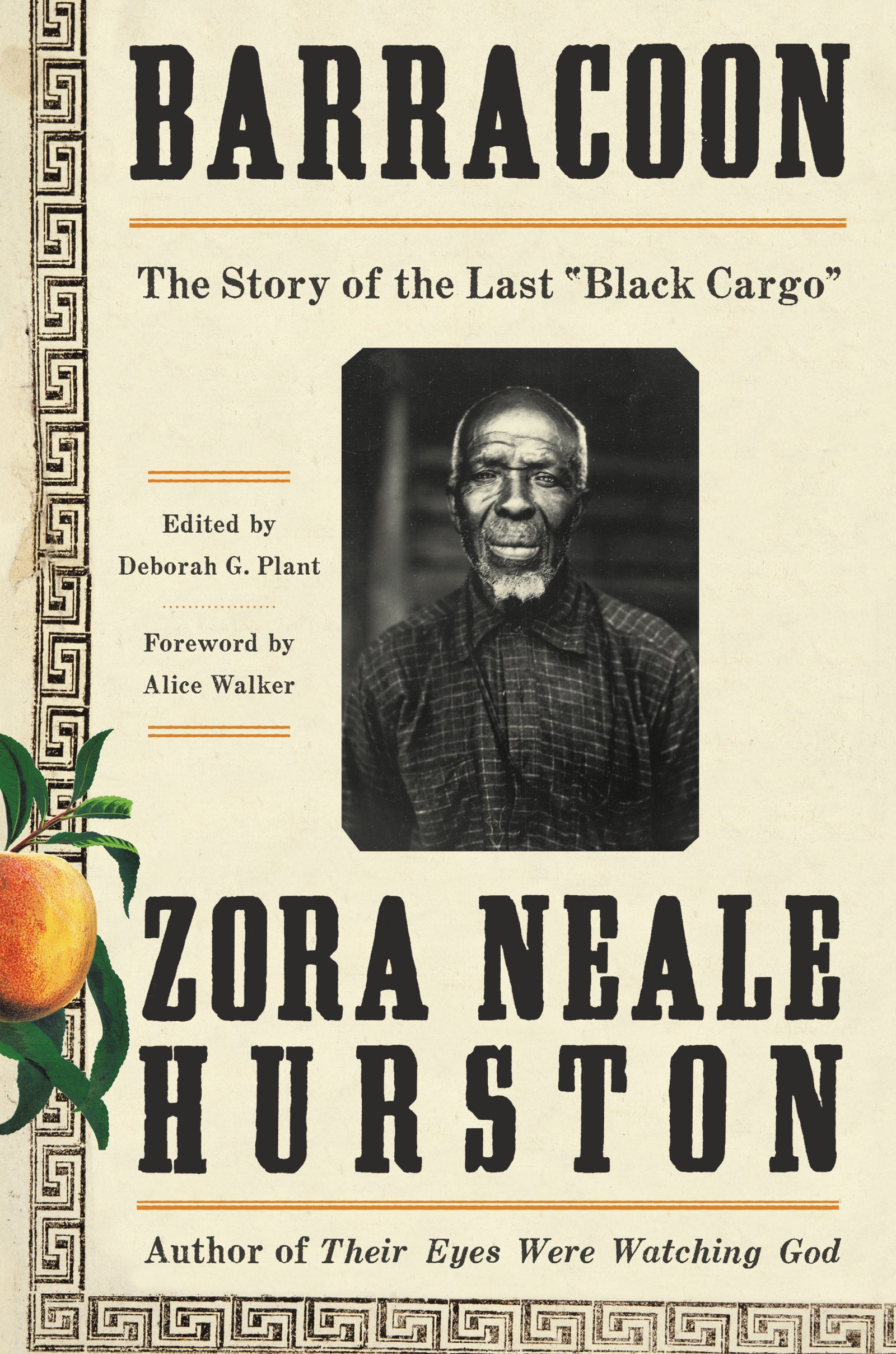

What a wonderful thing, in the year 2018, to have a new book by Zora Neale Hurston. It makes you wonder what they were thinking, all the people all those years ago, who declined to publish a book like Barracoon, Hurston's interview with the last survivor of the Mid-Atlantic slave trade. Perhaps they didn't understand what a rare and lucky moment it was, to have such experience still alive in the heart of a man, or perhaps they underrated Hurston's gifts and importance as an ethnographer (way more impressive, in my opinion, than her work as a novelist). There's some intimation in what I've read that people were squeamish about laying bare the role of African slavers in the Middle Passage, and quite rightly, since that stuff has always been fodder for right-wing trolls. But whatever the case, it's quite something to have a book like this published at last.

In 1927 Hurston traveled to Alabama to interview a man named Oluale Kossula, who had gone by the Americanized name Cudjo Lewis for over sixty years. As a teenager, Kossula's village in West Africa was decimated by the Kingdom of Dahomey, who were in the habit of massacring their enemies and selling whom they could to coastal slavers. The title, Barracoon, refers to the kind of barracks where captured Africans waited to be bought by slavers. One of the wonders of the book is that it gives a rare glimpse into what it was like on the African side of the slave trade. Kossula's account of the Dahomey warriors--apparently, traditionally women--is one of the most haunting aspects of his story.

When Kossula was carried away by the Clotilde, it was in violation of U.S. law, which had prevented new importing of slaves for over fifty years. The Americans who put the voyage together did so because they could, and because they felt like they were entitled to it. It was illegal, but no one, of course, got punished for it, except for Kossula. He actually touches very little on his experience of slavery, focusing on the life he led after emancipation with his wife and children. Like many former slaves, Kossula found himself needing to apply to his former masters for protection and employment:

"'Cap'n Tim, you brought us from our country where we had lan'. You mad us slave. Now dey make us free but we ain' got no country and we ain't got no lan'! Why doan you give us a piece dis land so we kin buildee ourself a home?'

"Cap'n jump on his feet and say, 'Fool do you think I goin' give you property on top of property? I tookee good keer my slaves in slavery and derefo' I doan owe dem nothin? You doan belong to me now, why must I give you my lan'?"

Kossula, then, with a group of fellow Africans, saved for years to buy their own land and found a community called Africatown. The community still exists in Mobile, and some of its residents still trace their heritage back to the Clotilde and the Dahomey raid. It's a remarkable story of independence and will, told in Kossula's own voice and idiom. Hurston deftly gets out of the way of Kossula's story, and records it with faithful care. Interpolation is smartly minimized to let the power of the story, and the feeling that you are hearing a firsthand account, shine through.

Kossula's experiences after the end of the Civil War were full of hardship. He talks about the way he and his family were looked on suspiciously by other black communities whose ancestors had come from Africa centuries ago. He talks about the tragic death of his wife and many of his children, including a horrible story of one son's death at a railroad crossing:

"I go through the crowd and lookee. I see de body of a man by de telegraph pole. It ain' got no head. Somebody tell me, 'Thass yo' boy, Uncle Cudjo.' I say, 'No, it not my David.' He lay dere by de cross ties. One woman she face me and astee, 'Cudjo, which son of yours is dis?' and she pointee at de body. I tell her, 'Dis none of my son. My boy go in town and y'all tell me my boy dead.'

One Afficky man come and say, 'Cudjo dass' yo boy.'

I astee him, 'Is it? If dat my boy, where his head?' He show me de head. It on de other side de track. Den he lead me home.

When Hurston finds Kossula, he is more or less alone. She does small errands for him and they share small joys, like crabs and a "huge watermelon" they "ate from heart to rind." She paints a picture of a man slowly abandoned by family, left in a land that never quite felt familiar to him, and who longs to return to "Afficky soil" before he dies. It's heartrending. But there is a small consolation in the thought that finally, more than 150 years after Kossula's kidnapping and enslavement, and over ninety years from the time that Hurston recorded his testimony, that the story of this proud and lonely man is finally able to be told.

No comments:

Post a Comment