(Spoiler alert, folks--if, like me, you've somehow avoided becoming familiar with King's books until now, you might want to turn back.)

The same painful image lies at the heart of Pet Sematary as Lincoln at the Bardo: a father lifting up the body of his deceased son, cradling it, unable to move past profound grief. For the spirits in Saunders' novel, it's a symbol of shocking compassion and intimacy, a physical embrace past the point where such things can reasonably be expected. In Pet Sematary, when the bereaved doctor Louis Creed steals his young son's body from the graveyard, the pathos runs the other way. It's so grotesque that it borders on squeamish black comedy:

Somehow, panting, his stomach spasming from the smell and from the boneless loose feel of his son's miserably smashed body, Louis wrestled the body out of the coffin. At last he sat on the verge of the grave with the body in his lap, his feet dangling in the hole, his face a horrible livid color, his eyes black holes, his mouth drawn down in a trembling bow of horror and pity and sorrow.

"Gage," he said and began to rock the boy in his arms. Gage's hair lay against Louis's wrist, as lifeless as wire. "Gage, it will be all right, I swear, Gage, it will be all right, this will end, this is just the night, please, Gage, I love you, Daddy loves you."

Louis rocked his son.

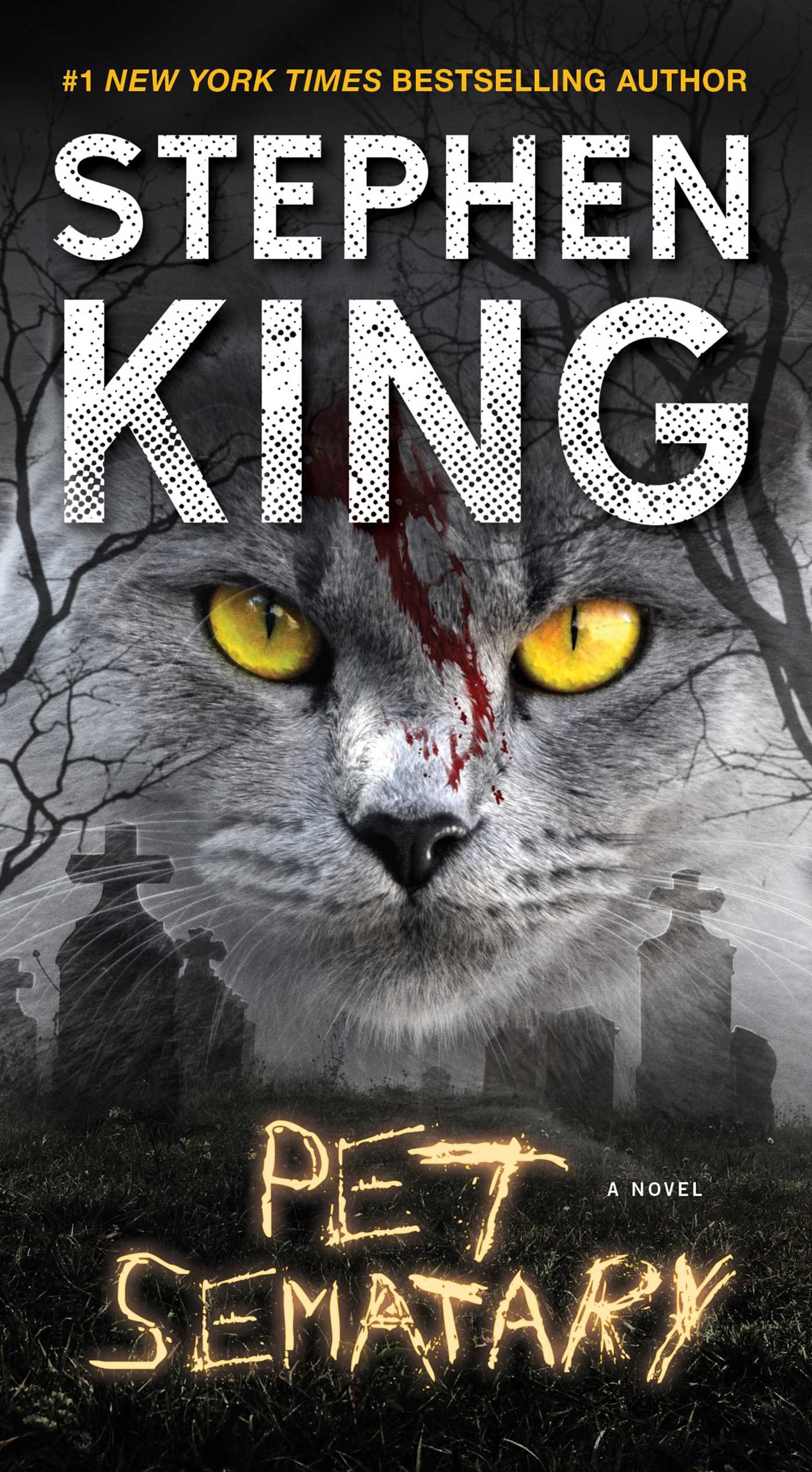

Louis' plan is to bury his son in the titular pet cemetery, an ancient Micmac burial ground that has the power to bring things back to life. The scenes in the burial ground are effectively eerie, filled with fog and unidentifiable noises and the great black shape of the Wendigo moving through the mud. Early in the novel he does the same thing with his daughter's cat Church, guided by an old Mainer who knows the supernatural history of the place. Distraught folks have been burying their pets there for years--and maybe a few people, too. Church comes back all wrong: torpid, bloodthirsty, without any kind of feline grace, and with an indelible stench of death. Chances are Louis's son Gage, hit by a truck in their front yard, will come back changed, too. But all the rational deliberation in the world can't overcome the depth of Louis' grief, and he goes through with the macabre plan despite knowing that.

Pet Sematary is a about 500 pages of meditation on the way death intrudes upon the banality of life, and another fifty pages of blood-soaked freakout horror. King paints the life of Louis, his wife Rachel, and his children Ellie and Gage, in painstaking detail. At times, too much detail--I'm not sure why we need to know, for instance, that "Rachel developed a mild infatuation with the blond bag boy at the A&P in Brewer and rhapsodized to Louis at night about how packed his jeans looked." But death, like it does, breaks in on the Creeds' life again and again: in the form of a young man hit by a car on Louis' first day of work at the student clinic at the University of Maine, in the form of their elderly nextdoor neighbor, in memories about Rachel's sick and resentful sister, who died as a child. Gage gets sick again and again, teasing you, almost, with the possibility of his death many times before it really happens. As a doctor, Louis knows all about death, about the fragility of the body, but against grief such rationalism is powerless.

I was amazed by how painstakingly King builds up the life of this family, and then destroys it breezily and mercilessly. The end, in which--hey, I meant that spoiler alert above--the toddler Gage comes back possessed by the murderous Wendigo and dispatches his own mother with a scalpel, was a real shock to me. I guess I had underestimated how much ice runs in King's veins. The message, I guess, is this: you'd better make friends with death, because you're just going to make it worse if you don't. In a way, it's not so different from Lincoln in the Bardo, which also tells us that there is a danger in holding on to grief for too long, but with a gentler spirit.

No comments:

Post a Comment