I drove back to Austin, under a Turneresque sunset with a gibbous moon rising from a bank of pink clouds. A herd of Black Angus cattle moved like shadows in the places where the buffalo once grazed. I thought about how unintentional most of life is. Part of me had always wanted to leave Texas, but I had never actually gone. Sometimes we are summoned by work or romance to move to another existence, and for me those moments when there is no reasonable alternative to departure have always been joyful, full of a sense of adventure and reinvention. Staying is also a decision, but it feels more like inertia or insecurity. Most of the time I live in a state of vague discontent, tempted by the vision of another life but unwilling to let go of the friends and daily habits that fill my time. When I am in other states or countries, I'm always aware of being in exile from my own culture, with all its outsized liabilities. I wish I lived in the mountains of Montana or on the Spanish Mediterranean. I wish I had a condo in a high-rise overlooking Central Park, with a piano by the window. These thoughts have been at play in my imagination for decades. Now here I was, on a darkening highway in Texas, with so much more road behind me than what lay before.

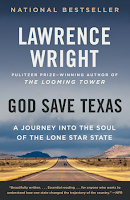

How hard it must be to write a book about Texas. Alaska may be bigger, but it's relatively unpeopled; to encompass Texas, you'd have to write about Houston's oil booms, Austin's weirdness, tensions on the Rio Grande. You'd have to talk about Dallas and Dealey Plaza, about the great nothingness in the middle, about Big Bend and the far west. Lawrence Wright's essay collection God Save Texas might not be Texas-sized; it's hard not to sense that in its attempts to cover every corner, it's missed some of the true mystery that lies along the way, but it's good enough for an outsider like me. From the first moment, when Wright describes biking along the path between San Antonio's historic Spanish missions, it whetted my whistle for the trip I'm taking next week, where I hope to do exactly that. (Let's hope those predictions of rain are exactly that.)

Wright brings a set of necessary skills to the project: he's a journalist, and much of the novel reads like well-researched journalism, especially the section about Houston that traces the history of the oil boom. Wright clearly has access to the chambers of the statehouse in Austin; he devotes two sections--titled "Making Sausage" and "More Sausage" to the conflicts within the Texas Legislature between moderate and ultra-conservative Republicans, and no one, it seems, is unwilling to talk to him--not even Karl Rove, who pops in for a queasy hello. I could have done with less of this stuff, maybe, because Texas's political scene is the least pleasant thing about the whole state, and I'd rather not think about it. But Wright, writing during the Trump administration, makes a powerful case that Texas is--shudder to think--the crucible of the American political scene. Ironically, given its iconoclasm, Wright suggests that Texas is at the forefront of American politics, and what we see there is soon to be what we see everywhere. It's hard to say he's wrong about that.

But Wright is a playwright, too, and much more pleasant are the sections where he uses his more writerly gifts to extol the state's grandeur and beauty. I loved the section about far west Texas, a severe desert where modern artists like Donald Judd found a landscape that could match the pure shape and color of their innovations. Chapters like "Borderlands" and "The High Lonesome," the latter ostensibly about the mid-Texas landscape that birthed musical icons like Buddy Holly, manage to capture in words something of Texas's sheer, mind-altering scale.

Wright, a Texan by birth, writes about returning to his ancestral land after sojourns in New York, Atlanta, Tennessee, and even as far away as Egypt. It's beautiful and difficult, I think, to return to the place whence you came, like the spiral returning; it has an air of backwardness, or perhaps of the final stages of something. But I find it easy, actually, to imagine that returning to Texas feels like home.

No comments:

Post a Comment