Whenever the boy and girl talk about child refugees, I realize now, they call them "the lost children." I suppose the word "refugee" is more difficult to remember. And even if the term "lost" is not precise, in our intimate family lexicon, the refugees become known to us as "the lost children." And in a way, I guess, they are lost children. They are children who have lost the right to a childhood.

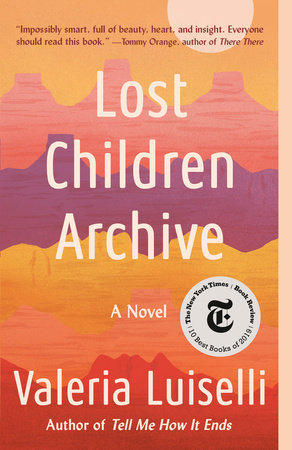

A family of four begins a cross-country road trip from New York City to Arizona. Mama is a documentarian who wants to record the stories of those affected by the separation of children at the U.S.-Mexico border; she has recently been working to help a friend locate her missing daughters, who have disappeared somewhere in those borderlands. Papa is a documentarist--as different, they say, as librarian from chemist--who wants to record natural soundscapes in the areas once occupied by Geronimo's Apaches, the last "free" people in revolt against the United States. In the backseat are his son, "the boy," and her daughter, "the girl," and together they are a somewhat makeshift, though precarious family: Mama, who narrates the first half of the book, isn't sure that what she and her husband are looking for on the trip is the same, and foresees that the end of the trip might also bring the dissolution of their marriage. But somewhere in the vicinity of the Chiricahua Mountains, the former stronghold of Geromino's Apaches, the boy, caught up in the stories his father and mother have told him about these many absent figures, takes his sister and runs away into the desert.

Who tells the story of the missing? How does one tell the story of the missing? For Papa, it's about recording emptiness: the natural sounds where people are not. It's also about imagination: the stories he tells the children about the Apache are obviously half-made up, a way of constructing a presence where non exists. (Papa, and the novel, perhaps pointedly and perhaps not, never seems to recognize that there are lots of living Apaches one might also record.) For Mama, the question is a fraught one over which she constantly agonizes. After hearing about it on the radio, they make their way for a rural New Mexico airport where a transport of children back to Mexico is taking place, and though they witness a small line of kids trooping from the hangar to the plane, most of what there is to see and document is stillness: a building, a plane. Even the boy becomes a documentarian/ist, with a Polaroid camera he's given for his tenth birthday. In this context, the fact that the children are undocumented takes on a special valence: Who will pay attention to them and how?

In Mama's section, this anxiety plays out through intertextuality, criss-crossed with a number of literary and journalistic sources that might help one make sense of the removal and disappearance of these children. Some are real books, fastidiously quoted and then indexed in interstitial lists of what's contained in the family's many moving boxes. I found this to be the least successful part of the novel, an attempt to write around a fundamental absence that left the narrative feeling overstuffed with ideas. Mama fixates especially on a fake book that tells a fable-like story of a group of children on a weeks-long train journey; it's pieces from this book--and others--that the boy adopts and reinterprets when the novel switches, halfway through, to his perspective. This section doesn't always work voice-wise, I thought, and even at ten his impulse to venture into the desert without his parents seems almost too thick-skulled to be believed. But it allows Lost Children Archive to escape some of the writerliness that makes the novel's first half seem sluggish.

In one cutesy detail, the kids each want to take their own empty moving box, to be filled with what they find on the trip. The girl ultimately fills hers with echoes: the sounds of people responding across a great distance, that turns out to be--for better or worse--the sound of us talking to ourselves. And yet, when the kids find themselves alone and lost in the Arizona desert, there is the chance that the echoes will turn out to be a real voice, searching for us as we are searching for it.

No comments:

Post a Comment