I recently realized something: many, many white people in the United State of America simply do not think that slavery was all that bad. It becomes quite obvious when I hear someone like Roy Moore say that "even though we had slavery," America was greatest before the Civil War because we had strong families. (Never mind that slavery tore family after family apart, as Uncle Tom's Cabin shows quite well.) Or I read stories like this one from Vox, where a docent at a Southern plantation recounts some of the questions she received, like, "Did the slaves here appreciate the care they got from their mistress?" It stands out quite clearly when people defend the statues of Confederate generals, because of how upright they were despite their defense of slavery. That "despite" says a lot. The most humbling thing about this realization is that I had it at all; all of this has doubtlessly been clear to black Americans for hundreds of years.

I bring this up because the most striking thing about Uncle Tom's Cabin is how it captures the rationalizing, the hemming and hawing, the rhetorical and political cowardice of white Americans. Uncle Tom lives with his wife and children in Kentucky under a kindly man who treats his slaves well and promises never to separate them, and yet, when money is tight, he does exactly that. From there he's purchased by a compassionate but indolent man named St. Clare, who slowly but surely is convinced to do something about the injustice of slavery and set Tom free--and ends up getting killed in a bar fight on his way to draw up the papers. It's St. Clare who delivers the stirring monologue up top, recognizing that slavery itself is an abuse that can't be ameliorated by treating your slaves well, but it takes the superhuman patience and goodness of a man like Tom to drag St. Clare to do what he already knows what's right. And the fact that it's too late just goes to show how right he was; his own kindness to Tom amounts to nothing when his proud, selfish widow sells Tom to the vicious Simon Legree. Time and time again, Stowe shows us the mental gymnastics necessary for white Americans, slaveowners and otherwise, to keep their egos intact.

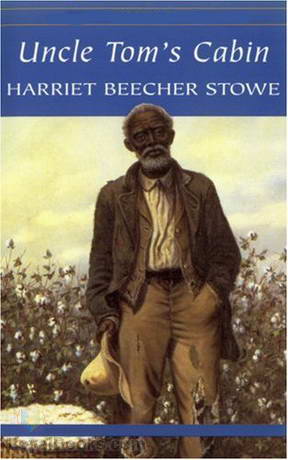

Uncle Tom himself has given his name to a rather nasty epithet. But the character Tom couldn't be farther from the stereotype of the black betrayer who sides with his masters, although he does form strong and compassionate relationships with many of them. Rather, Tom is a picture of perfect Christian goodness, designed to emphasize the injustice slavery does to good people. This is best exemplified by the moment when Tom refuses an order by Legree to beat another slave--a typical tactic meant to divide slaves and pit them against one another. Tom has no problem recognizing Legree's ownership and mastery over him, but he claims a higher allegiance to God. In doing so, Tom seals his own death warrant, turning Legree's petty viciousness into an unquenching resentment, and turns Tom into very much a Christ figure himself. It's hard to square that act--the pointed refusal of his owner's command, at his own severe expense--with the image of the traitorous, sycophantic "Uncle Tom."

Jane Smiley has suggested that we should read Uncle Tom's Cabin in schools instead of Huckleberry Finn, which she finds wanting in its attitude towards black Americans. I can't get behind that. First of all, Uncle Tom's Cabin is twice as long, and contains long stretches of inaction that would make it hell to teach, compared to the zippy Huck Finn. It also drops an important and exciting plot thread--that of a couple of escaped slaves named George and Eliza--for literally hundreds of pages in favor of the tedious exploration of St. Clare's saintly little girl, Eva. But what makes Huck Finn such a rewarding book to teach is its complexity and nuance, and one of my favorite things to do in class is to ask students to evaluate its attitude toward race. You couldn't do that with Uncle Tom's Cabin, which is written in the polemical mode and lacks that kind of complexity. As a polemic, it's terrific--the best and most influential polemic we ever produced in America, probably--but I doubt it would work well in a classroom.

But that doesn't mean we should stop reading it. It has been credited with reshaping American attitudes toward slavery in advance of the Civil War, and sad to say, I think there are still those in need of its message.

No comments:

Post a Comment