In any case, the dog coming from Jerome rather than Sedona was telling, people thought.

Another something that could be the basis of the dog's behavior was the fact that her mistress always wore sunglasses, day and night. Like everybody else, the dog never got to see her eyes. When the woman had people over, she placed a big bowl of sunglasses outside the front door and everyone put on a pair before entering. It was easier than locking the dog in the bedroom.

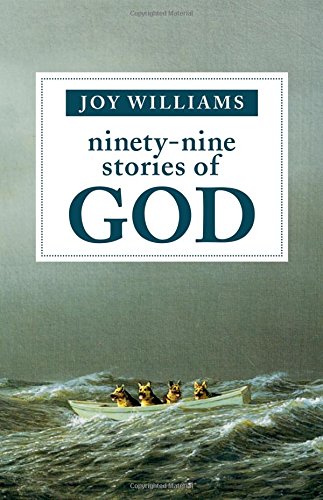

The Lord is a recurring character in Joy Williams' Ninety-Nine Stories of God. He's not the only character, and you can draw your own conclusion about what it means to call the eighty-odd stories in which he's not a character "stories of God." For His part, the Lord isn't quite lordly in these stories. Typically, we see him engaged in pretty commonplace human behavior. "The Lord was invited to a gala," one begins. Another first line is: "The Lord had always wanted to participate in a demolition derby." Another, perhaps less commonly, begins "The Lord was in a den with a pack of wolves." The image that Williams gives us of God is one who is relatable, but still unknowable; not omniscient--he has trouble winning the raffle to participate in the demolition derby--but who knows at least a little bit more than we do.

The longest of Williams' stories runs about three small pages; the shortest are single sentences: "We were not interested the way we thought we would be interested." That story is called "MUSEUM," and like all the stories in the collection, the title comes at the end, rather than the beginning. This has the effect of turning the title into a kind of punchline:

When he was a boy, someone's great-grandfather told him this story about a traveler in thirteenth-century France.

The traveler met three men pushing wheelbarrows. He asked in what work they were engaged, and he received from them the following three answers.

The first said: I toil from sunrise to sunset and all I receive for my labor is a few francs a day.

The second said: I'm happy enough to wheel this wheelbarrow, for I have not had work for many months and I have a family to feed.

The third said: I am building Chartres Cathedral.

But as a boy he had no idea what a chartres cathedral was.

PERHAPS A KIND OF CAKE?

That's pretty funny. But it also resembles a Zen koan, a question with no real or satisfactory answer. In this story, the effect is to trouble the point of the great-grandfather's narrative. The great-grandfather wants his great-grandson to see the way in which our experience is defined by our perspective, apart from literal fact, but the great-grandson's lack of understanding somehow both confirms the lesson and prevents him from "getting" it.

And in the same way, these stories refuse to be "got." They're highly elliptical, and leave more out than than they leave in. They remind me of what someone once said about the band Spoon: they take out every track that's not absolutely essential, and then they take one more. Check out the story in the italics above and notice how much we're not told about the dog or its owner; we don't even get to know what behavior the dog exhibits that's so troubling. This, too, is a "story of God," a story about the inherent inscrutability of the universe, which refuses to bend to our expectations of causality and rational observation.

I loved these stories, and I'm excited to show them to my creative writing students, whose fiction often stalls out at five or six pages of background, well before any narrative thrust can really get going. Look at how much you can do with how little, I'll tell them, and it's a lesson I'm excited to reflect on for my own writing, too.

No comments:

Post a Comment