In Ocracoke, on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, there is a very short street called Styron. It's one of the old local families whose names you see everywhere--just up the road, on the other side of town as far as that goes, there's a Styron's General Store. I don't know if William Styron is one of those Styrons, but I wouldn't discount it. Virginia's Tidewater area, the wide coastal plain centered on the megalopolis of Hampton Roads, is the most accessible nearby region to the Outer Banks, far more so than the inner cities of North Carolina itself. There are certain difficult-to-describe affinities between the islands and the Tidewater that resonated, as I hoped they would, during the past week I spent there on vacation. (And until someone writes a good book about the Outer Banks, it's probably as close as you can get.)

A Tidewater Morning is a set of three stories, presented as childhood memories, of a Tidewater native named Paul Whitehurst, who is pretty clearly Styron's stand-in. Two of them center on war: In "Love Day," a twenty-year old Paul is serving on a cruiser in the Korean War when he realizes, thanks to an abrupt memory of his father, that he actually hates, and does not love, the war he's fighting. In the title story, a thirteen-year old Paul draws a connection between the headlines of impending war in Europe, emblazoned on the newspapers he carries, and his mother's worsening cancer. "Love Day" is a tight little knot of a story, that shuffles effortlessly between several clustered memories; "A Tidewater Morning" is so loose and shaggy it feels like a stunted novel. Both boast a writerly knack for sharp observation and a plainspun but effective style that impresses me more here than it did in The Confessions of Nat Turner.

The best story, "Shadrach," is in the middle. In it, a young Paul is hanging out with a local family who, over many generations, have fallen from the height of Virginia society, and become hicks. An elderly black man appears in a car, too old even to control his bodily functions, but who has trekked nevertheless from the Deep South to die on the land where he was born, and served, as a child, as a slave:

I had no way of knowing that if his long and solitary journey from the Deep South had been a quest to find this millpond and for a recaptured glimpse of childhood, it might just have readily been a final turning of his back on a life of suffering. Even now I cannot say for certain, but I have always had to assume that the still-young Shadrach who was emancipated in Alabama those many years ago was set loose, like most of his brothers and sisters, into another slavery perhaps more excruciating than the sanctioned bondage. The chronicle has already been a thousand times told of those people liberated into their new and incomprehensible nightmare: of their poverty and hunger and humiliation, of the crosses burning in the night, and above all, the unending dread. None of that madness and mayhem belongs in this story, but without at least a reminder of these things I would not be faithful to Shadrach. Despite the immense cheerfulness with which he had spoken to us of being "dibested of mah plenty," he must have endured unutterable adversity. Yet his return to Virginia, I can now see, was out of no longing for the former bondage, but to find an earlier innocence. And as a small boy at the edge of the millpond I saw Shadrach not as one who had fled darkness, but as one who had searched for light refracted within a flashing moment of remembered childhood. As Shadrach's old clouded eyes gazed at the millpond with its plunging and calling children, his face was suffused with an immeasurable calm and sweetness, and I sensed that he had recaptured perhaps the one pure, untroubled moment in his life. "Shad, did you go swimming here too?" I asked. But there was no answer.

How does a white person write about black people? I've been thinking a lot about that question. I can't accept that the answer is just not to do it, because writing fiction is a necessary kind of seeing. Styron struggled with that question, too, and in Nat Turner came up with answers that many found wanting. I don't think that either I or Styron have the standing to say whether "Shadrach" is more successful. But I do see some possible answers in it to that question. One, by placing the story within the larger historical context that we whites are so easily able to ignore. Two, with a self-conscious distance, and an eye toward the writer's own limitations. Paul never pretends to know Shadrach, but by giving an account of him he rejects the false choice between understanding and ignorance. The story is never "about" Shadrach in the way that it is about Paul--how could it be?--but it doesn't seem to shy away from anything, either. Whatever its quality, Nat Turner does the first but certainly not the second.

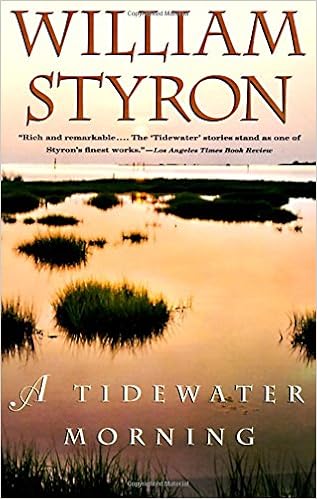

In the end the thing in A Tidewater Morning that resonated most with my Outer Banks trip was that cover, which perfectly captures the special quality of afternoon light when it falls along the marsh. But books about the South, when they're true--in the larger sense, not just non-fiction, though I suspect much of these stories is non-fiction--resonate with me like no other books can.

No comments:

Post a Comment