John Durbeyfield, town drunk, happens to discover one day that he is actually the descendant of a once-great family, the d'Urbervilles, of whom a few still-genteel relations remain. Hoping for monetary advancement, Durbeyfield sends his young daughter Tess to make the acquaintance of their cousin, Alec d'Urberville. Alec's interest in Tess is not entirely that of a friendly relative, and Tess must repeatedly deflect his crass come-ons. Then, one evening, while she is captive in his carriage, he rapes her. Hardy, with his usual circuitousness, never quite says this--but the second chapter is called "Maiden No More."

Tess of the d'Urbervilles is the story of the consequences of rape. It would be nice to think that it's a record from the foreign nation of the past, and that Tess' experience would be different today, and maybe it would, but in degree and not in kind. Like many rape victims today, Tess is thrown together again and again with her violator, unable to break free. Like many rape victims today, she is blamed--explicitly and otherwise--for her rape, including by the love of her life, Angel Clare, whose rigid humanist morals are unable to tolerate what he perceives as Tess' indiscretion. Tortured by male attention, she mutilates her own face:

As soon as she got out of the village she entered a thicket and took from her basket one of the oldest field-gowns, which she had never put on even at the dairy... She also, by a felicitous thought, took a handkerchief from her bundle and tied it round her face under her bonnet, covering her chin and half her cheeks and temples, as if she were suffering from toothache. Then with her little scissors, by the aid of a pocket looking-glass, she mercilessly nipped her eyebrows off, and thus insured against aggressive admiration she went on her uneven way.

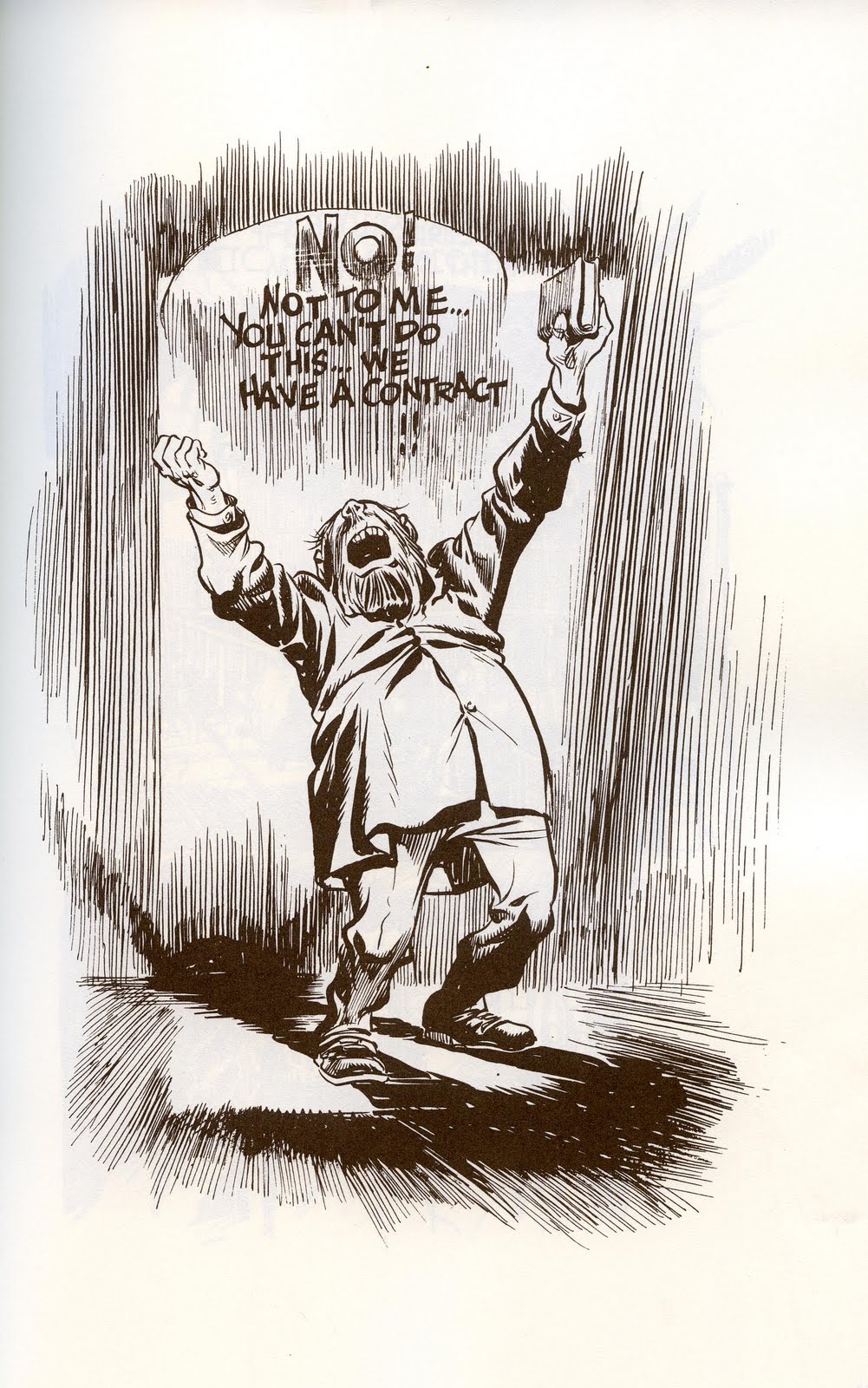

D'Urberville is one of the slimiest villains I think I've ever read about. His constant wheedling of Tess, his feigned care, contrasted with his claims to be so inflamed with passion that he can't resist himself, are both reprehensible and recognizable. True, Hardy leaves some space for the reader to interpret Alec's actions as a seduction, but it seems to me that Hardy's structuring of the power differential between the two figures--he is wealthy and powerful, she neither, and of course if she resists he may abandon her in the woods. But Angel, the good man whose moral code is so inflexible, is more frustrating and maybe more repulsive. Angel takes a voyage to South America to get rid of the sticky moral situation that is Tess, only belatedly realizing his error:

During this time of absence he had mentally aged a dozen years. What arrested him now as of value in life was less its beauty than its pathos. Having long discredited the old systems of mysticism, he now began to discredit the old appraisements of morality. He thought they wanted readjusting. Who was the moral man? Still more pertinently, who was the moral woman? The beauty or ugliness of a character lay not only in its achievements, but in its aims and impulses; its true history lay, not among things done, but among things willed.

Moral realizations in Hardy's novels are always a step too late, sometimes comically so--it seems like lovers are always a moment too late or early to reunite with each other--but I guess we should take Angel at his word and judge him by this intentions and not his achievements. But his obtuseness is pretty angering.

What about Tess? She's not as interesting as the male principals--smart, pretty, humble, etc.--but much of her identity is tragically consumed by her victimhood. She's a sister in spirit to Jude the Obscure: neither can seem to catch a break, and both are so dogged by systemic unfairness and outright cruelty that they begin to internalize it. Hardy clearly loves her, sometimes to a fault, and subtitles the novel "A Pure Woman Faithfully Presented." Like Angel Clare, he's more arrested by pathos--pity--than beauty, and Tess is certainly a figure of pity. There's no place for Tess, partly because of the backward moral climate of her surroundings. But the pathos comes not only from the cruelty of a rotten society but from a cosmic unfairness:

Care had been harsh toward her; there is no doubt of it. Men are too often harsh with women they love or have loved; women with men. And yet these harshnesses are tenderness itself when compared with the universal harshness out of which they grow; the harshness of the posititon towards the temperament, the means toward the aims, of to-day towards yesterday, of hereafter towards to-day.

.jpg/200px-TheDivineInvasion(1stEd).jpg)