Bunny gropes around on the bed until he finds the remote and, with a crack of static, the TV implodes into nothingness and he closes his eyes. A great wall of darkness moves toward him. He can see it coming, vast and imperious. It is unconsciousness and it is sleep. It moves like a great tidal wave but before it breaks over him and he is away, before he renders himself completely to that oblivious sleep, he thinks, with a sudden, terrible, bottomless dread, of Avril Lavigne's vagina.

Bunny gropes around on the bed until he finds the remote and, with a crack of static, the TV implodes into nothingness and he closes his eyes. A great wall of darkness moves toward him. He can see it coming, vast and imperious. It is unconsciousness and it is sleep. It moves like a great tidal wave but before it breaks over him and he is away, before he renders himself completely to that oblivious sleep, he thinks, with a sudden, terrible, bottomless dread, of Avril Lavigne's vagina.Nick Cave has two personae. The one I was first familiar with was the brooding, Gothic piano player of As I Sat Sadly By Her Side, but that was a later invention. The original Cave was the frontman for an Australian band called The Birthday Party, and that Cave is loud, brash, and quite filthy. It's that persona that Cave would return to for his Grinderman side project, who recorded this:

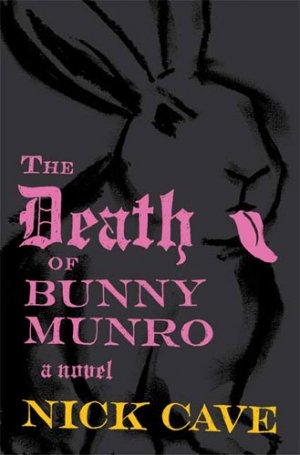

The Death of Bunny Munro was written by this Cave. It is a junkyard clattering of death and sex, as bitter as it is squalid. The titular character is a middle-aged traveling salesman with a sex addiction that has irretrievably alienated him from his wife, and when she commits suicide he takes their son, Bunny Junior, and drags him on a whirlwind tour of the south of England as he tries to hawk his wares and chase poon at the same time.

Bunny is a horrendous man. His need for constant sexual fulfillment puts him through mental and physical hardship and distracts him from his son, a prepubescent egghead who absorbs himself in his comprehensive (but somehow, single-volume) encyclopedia. Bunny Junior idolizes his father, but doesn't truly understand him:

His mother bought the encyclopaedia for him, just because she loved him to bits, the boy likes to remember. Bunny Junior thinks it is an elegant-looking book with a jacket the exact colour of one of those citronella-impregnated mosquito candles. Merlin was the son of an incubus and a mortal woman, and the boy looks up 'incubus' and finds that an incubus is a malevolent spirit who has intercourse with women in their sleep, then he looks up 'intercourse' and thinks, Wow, imagine that, as he gradually intuits the presence of his father standing in the doorway.

Bunny, of course, is defined solely by "intercourse." In turn, Bunny doesn't care to even try to know his son, and instead spends most of his spare time thinking on Avril Lavigne's vagina. This is a frequent conceit, and Cave even apologizes to Avril at the end of the book, but the pointed realness of it reminds me of similar complaints I had about J. G. Ballard's sexualization of Elizabeth Taylor.

Cave dangles a couple more limbs from his Frankenstein's monster: First, there is the Horned Killer, a serial murderer in a red cape and horns making his way south through England while flaunting the media. The Horned Killer is a metaphor for the promised death of the title (which, you will notice, may refer to either Bunny or his son), winding its fated path to Brighton. Second, the ghost of Bunny's wife insists on haunting both Bunny and his son.

Add this to the noisy, ostentatious prose--you can almost see Cave sweating from the effort--and it's all too much. Beneath the clutter, The Death of Bunny Munro is a simple tale about a man, too sad to be vile, whose subservience to his addictions destroys his relationships. Despite his attempts at misdirection, Bunny ends up exactly where you expect. It isn't necessary for Bunny to be redeemed, but there is little enjoyment in watching a distasteful man fail distastefully.

Aristotle tells us that a tragic hero must be neither wholly good nor bad, so that we may see ourselves in him and feel both pity and fear, but when Bunny walks into a client's home and rapes a near-comatose girl because she looks like Avril Lavigne (seriously), following him to the end becomes a bitter chore.

This is Cave's second book, after The Ass Saw the Angel, separated by a twenty-year gap. Clearly, his schedule in the last twenty years has been fairly full (besides his solo work and Grinderman he has scored several movies), but with that kind of time, you would hope Cave's creative impulse would have produced something so sordidly mean.

No comments:

Post a Comment