It was true that in spite of what the Brotherhood had done, there was something that it would never be able to kill in this city: its memory. The memory of the city as it used to be, filled with old noises, with murmurs of rainstorms five years past, with the invigorating laughs and the ever-present smells. All of these things, the had-beens of Kalep, its memory, would never disappear, at the very least not as long as the people refused to forget them. He believed this was where the real battle was. Every war, in his eyes, was a war for memory, in other words a war that must be fought in the name of the survival of memory.

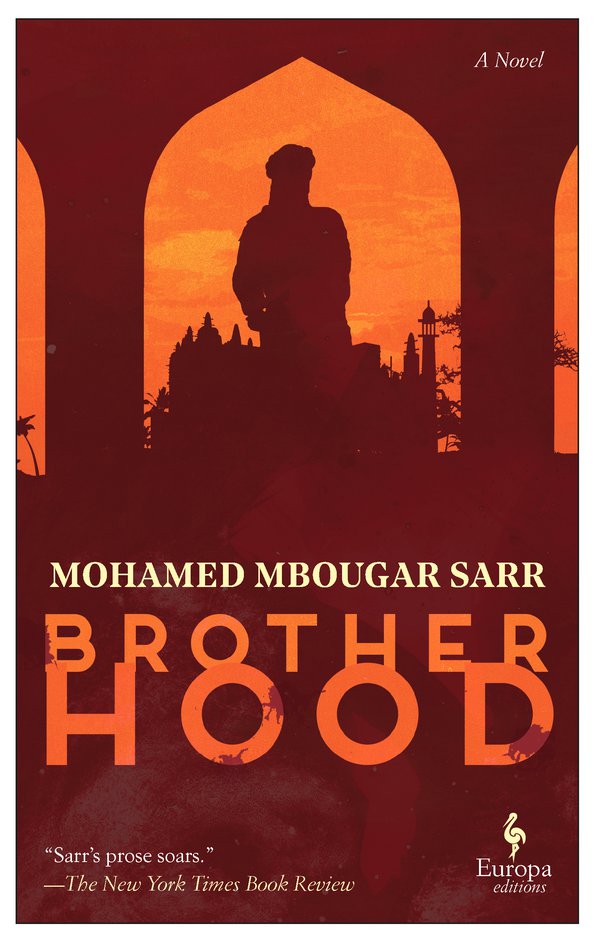

The Senegalese city of Kalep has been under the yoke of an Islamic fundamentalist group calling itself the Brotherhood for years. Their rule is harsh and violent: the novel begins with the beheading of two unmarried lovers, caught by the Islamic police. In the basement of a local bar, a resistance group forms, centered around the doctor Malamine, whose wife Ndey Joor has been badly beaten for not wearing her veil in public, and whose son Ismaila left years ago to join the fundamentalists. Along with a handful of others, Malamine prints a newsletter detailing the crimes of the Brotherhood, exposing its cruelty and provoking the locals to resist. Meanwhile, the calculating, vicious leader of the Brotherhood, Abdel Karim, vows to track down whoever is behind the newsletter and punish them.

Man, I did not think this book was good. I can't remember the last time I read a book that felt so punishingly didactic. Take, for instance, the moment where Malamine's son Idrissa reflects on how the Brotherhood has made it difficult for him to talk to his mother, Ndey Joor. "By relieving them of their right to speak," Mbougar Sarr writes, "the Brotherhood was also relieving them of their need to speak." He then writes, "Every authoritarian regime rises in this way: it manages to convince its people of the futility of communication." Well, who's thinking that? Not Idrissa! Why would he know that "every authoritarian regime rises in this way?" Time and time again, the narrative abandons the immediacy of the characters for abstract political theorizing like this. And rarely are these moments illuminating. The characters become avatars of political struggle; they rarely talk or react like real people. One night in the basement of the bar, Malamine looks at his comrades and assigns each of them an abstract principle:

Dethie was freedom. Codou was Justice. Madjigueen was Equality. Vieux was Denial. Alioune was Beauty. Pere Badji was Mystery. Man was all of these qualities together.

This just doesn't work, I think. It's like an old medieval morality play, but it's not a story that really illuminates the life of people living under fundamentalist regimes.

What worked best about the novel was the exchange of letters between Aissata and Sadobo, the mothers of the two lovers killed in the novel's opening scene. One mother appeared as witness, the other stayed home. In their letters, they discuss--again, much too abstractly, but in a way that is more rooted in real feeling--how to respond to the harsh rule in which they live. This story was, I thought, much more interesting than the "main narrative" about the resistance (all they do is print a newsletter???). That's the novel I sort of wish I had read.

Sadly, I didn't like this book. On a happier note, the addition of Senegal means my "countries read" list is up to 65!

No comments:

Post a Comment