"Never love a wild thing, Mr. Bell," Holly advised him. "That was Doc's mistake. He was always lugging home wild things. A hawk with a hurt wing. One time it was a full-grown bobcat with a broken leg. But you can't give your heart to a wild thing: the more you do, the stronger they get. Until they're strong enough to run into the woods. Or fly into the woods. Or fly into a tree. Then a taller tree. Then the sky. That's how you'll end up, Mr. Bell. If you let yourself love a wild thing. You'll end up looking at the sky."

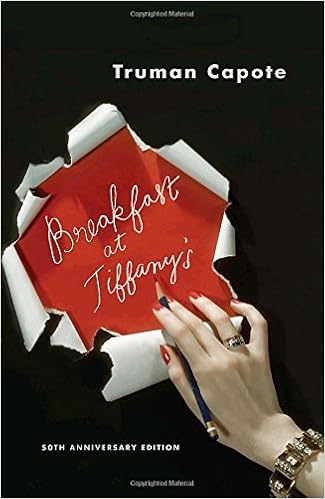

There's a funny moment in Truman Capote's Breakfast at Tiffany's where the narrator, Fred, and Holly Golightly are talking about Fred's stories, and Fred asks her to name a work that means something to her. Wuthering Heights, she says. That's not fair, says Fred, that's a work of genius. "It was, wasn't it?," Holly replies. "My wild sweet Cathy. God, I cried buckets." She's talking about the movie.

It's funny because it's difficult to talk about Breakfast at Tiffany's without reference to the Audrey Hepburn film. I've never seen it (I know) so I was able to read the novel with fresh eyes; Brent, on the other hand, tells me that he saw the movie before reading the novel and the difference between them really soured the book for him.

But it's also a great character moment that gets to the heart of who Holly Golightly is, and why she's so captivating, not just for Fred, but for the reader. She's sensitive and intelligent, but somehow also incredibly obtuse and naive; she's defensive about her own sophistication--a trait which stems from her childhood as a rural child bride, of all things--but with a deep philistine streak. In today's ergot she'd be a manic pixie dream girl, one of those characters defined by their endearing quirkiness, though I think Capote's queerness keeps him from turning her idiosyncrasies toward sexual objectification. Ultimately, she's a tragic figure: a woman whose outsized personality and charm attracts everyone around her, including assholes and criminals. The character she reminds me of most is actually Jay Gatsby, another provincial whose self-transformation into a glamorous icon is derailed by the shallow and the venal.

It's a slim novel with a handful of standout moments--my favorite kind. There's the appearance of Holly's former husband, Doc, a horse farmer from Tulip, Texas, who Fred mistakes at first for Holly's father. There's the sudden death of Holly's brother, also named Fred, in the war--despite her multitude of attachments, the only man who has her entire devotion. There's the moment at the end o the novel where Holly, running to the airport to escape prosecution on charges of criminal conspiracy, abandons her nameless cat, a wild thing, only to make the cab stop ten blocks later and go back so she can find it again. These moments work because Holly is such a confidently and clearly drawn character, up there, I think, with folks like Holden Caulfield in the truest characters of 20th century American novels.

No comments:

Post a Comment