It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

I begrudgingly concur with the department lead at my school who recommended that we read

Black Boy as the final book of the senior year instead of what he calls "the pink book"--since our copies of

Pride and Prejudice are the color of Pepto-Bismol. Surely he is right when he says that

Pride and Prejudice is not a book that teenagers would find inherently interesting, and its feminine appearance doesn't help (though I leave the irony of judging this particular book by its cover to the reader to notice).

But I also admit that I was secretly pleased to find that there were only enough copies of

Black Boy to be read by one class. I love

Pride and Prejudice. This puts me in good company, since it seems that in recent years

sequels to

Pride and Prejudice have

become sort of a

cottage industry.

But why? What is it about "the pink book" that has made it such an enduring work?

I think part of its popularity has to do with the fact that it is sort of an ur-text for a very familiar type of story: the romantic comedy. All romantic comedies are structured essentially the same way: Two people of very different stations or perspectives meet, and at first their natural opposition makes them hate each other. Inevitably, despite all odds, their mutual antipathy turns to love.

Surely

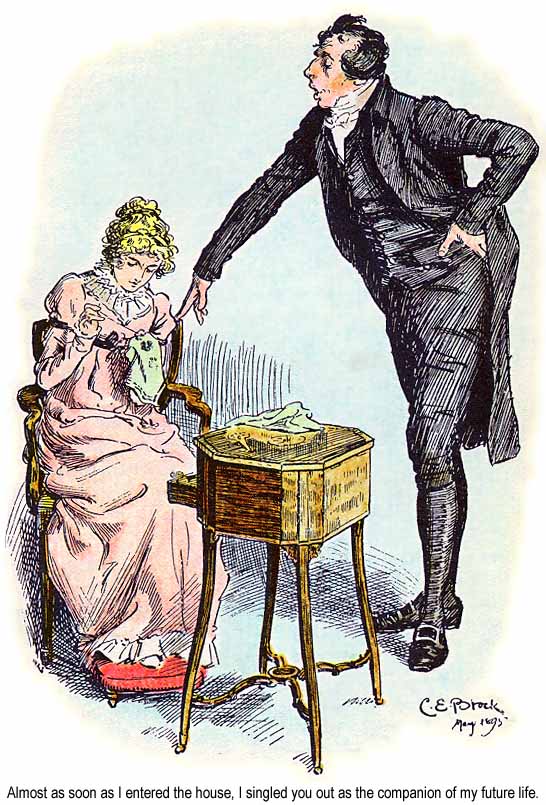

Pride and Prejudice wasn't the first to do this, but it does it so well. Elizabeth Bennet's cleverness and disdain clash immediately with Mr. Darcy's prim elitism, but the reader sees what they do not, that their intelligence and discernment (or even snobbishness) make them perfect for each other. As I've been teaching it, I try to get across what might be lost on a young, modern audience, that Darcy and Elizabeth's love forms across class boundaries, and that Darcy's love for Elizabeth represents a non-trivial social risk.

Furthermore, I think that

Pride and Prejudice taps directly into that well of human feeling that romantic comedies exploit repeatedly, the desire to find one's soulmate. Darcy and Elizabeth are drawn just broadly enough to allow the reader to live vicariously through them; Darcy is handsome, well-mannered, eloquent, but also appealingly aloof. Likewise Elizabeth is clever and strong-willed. Not only is it easy to imagine ourselves in a relationship with (or someone like) one, it is easy to imagine ourselves as (or like) the other. We love the story because it affirms the archetype of finding "the One."

And, like romantic comedies ought to be, it's funny. This is especially lost on my students, who fail to pick up on the humor underneath the language. In this scene, Mr. Bingley's sister Caroline betrays her crush on Darcy, who earlier had remarked how he appreciates a woman who reads frequently:

Miss Bingley's attention was quite as much engaged in watching Mr. Darcy's progress through his book, as in reading her own; and she was perpetually either making some inquiry, or looking at his page. She could not win him, however, to any conversation; he merely answered her question, and read on. At length, quite exhausted by the attempt to be amused with her own book, which she had only chosen because it was the second volume of his, she gave a great yawn and said, "How pleasant it is to spend an evening in this way! I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading! How much sooner one tires of anything than a book! When I havea house of my own, I shall be miserable if I have not an excellent library."

No one made any reply. She then yawned again, threw her book, and cast her eyes round the room in quest of some amusement...

I think the image of Caroline saying "How much sooner one tires of anything than a book," and then tossing her book aside when no one responds, is pretty amusing. But you know what they say about what happens to a joke when you explain it. Much of the humor is subtle, and based on changes in register that modern readers have trouble picking up on:

Sir William Lucas had been formerly in trade in Meryton, where he had made a tolerable fortune and risen to the honour of knighthood by an address to the King, during his mayoralty. The distinction had perhaps been felt too strongly. It had given him a disgust to his business and to his residence in a small market town and quitting them both, he had removed with his family to a house about a mile from Meryton, denominated from that period Lucas Lodge, where he could think with pleasure of his own importance, and unshackled by business, occupy himself solely in being civil to all the world.

The humor here lies in the diction: Lucas' house, "denominated from that period Lucas Lodge," his "tolerable fortune," all endowing the passage with a false grandiloquence that shows exactly why Lucas has felt "the distinction... too strongly." Lucas is a pompous ass, and has given up any useful contribution to society to "occupy himself solely in being civil to all the world," enamored of his own fortune and relatively paltry social status. But to recognize the different shades of meaning here requires a much more sophisticated sense of vocabulary than even the brightest teenagers possess.

Still, I hope to kindle in at least one student an appreciation of how good

Pride and Prejudice is. If I can do that, then I will count this semester a grand success.