There is claiming the land, which Ba wanted to do, which Sam refused--and then there is being claimed by it. The quiet way. A kind of gift in never knowing how much of these hills might be gold. Because maybe if you only went far enough, waited long enough, held enough sadness pooled in your veins, soon you might come upon a path you knew, the shapes of rocks would look like familiar faces, the trees would greet you, buds and birdsong lilting up, and because this land has gouged in you an animal's kind of claiming, senseless to words and laws--dry grass drawing blood, a tiger's mark in a ruined leg, ticks and torn blisters, wind-coarsened hair, sun burned in patterns to leave skin striped or spotted--then, if you ran, you might hear on the wind, or welling up in your own parched mouth, something like and unlike an echo, coming from before or behind, the sound of a voice you've always known calling your name--

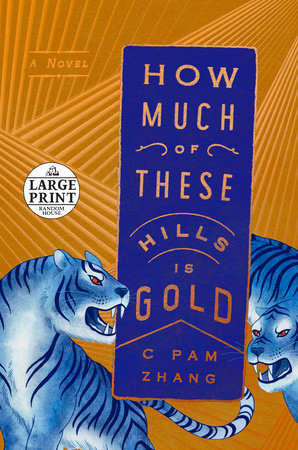

Lucy is a young Chinese-American girl living in the gold rush region of the American West in the nineteenth century. Since the death of her mother, her little sister Samantha has cut her hair short and taken to calling herself Sam, posing as a boy. When Lucy and Sam's father--known as "Ba"--dies suddenly in the night, the pair end up alone in this frontier land, and without a way to stay in their house, they set out into the wilderness to find a place to bury Ba's putrefying body.

How Much of These Hills is Gold wrenches the reader through several chronological shifts: no sooner is Ba's body buried than Zhang winds back the clock several years to illuminate the kind of hardscrabble life the family lived before the death of Ma and Ba. Ba, it turns out, was one of the very first to discover gold in the California hills, a secret he has been keeping--and mining--for years, but when the secret gets out, it's only a matter of time until white men find a way to use his race to lock him out of the munificence of the gold rush.

There's even an As I Lay Dying-style section written from the point of view of Ba's corpse as he rides on back of Lucy and Sam's horse, written as a farewell to Lucy in which he fills in the history of his own relationship with their mother and his first experiences in what the Chinese called, appropriately enough, Gold Mountain. This section, I thought, was one of the most successful of the novel--despite its fancifulness, Ba's voice grounds the narrative; I found the third-person present-tense mode of the rest of the novel to be a little too precious at times.

From there, the novel zooms forward again five years, when Lucy and Sam meet again for the first time after splitting up in the wilderness. Lucy has found safety and comfort in a frontier town, attaching herself to a vain, rich white girl; Sam has been an adventurer in the hills, in the spirit of long-dead Ba. The two are foils in many ways: civilized and wild, assimilating and proudly Chinese, feminine and masculine, Ma and Ba. Against the backdrop of the Wild West, Zhang explores these themes of race, gender, and identity with a great deal of subtlety and complexity. But the story never quite recovers from the time jump, I thought, and tries to fill in too much. Still, How Much of These Hills is Gold offers a new and welcome perspective on the familiar myths of the West.

No comments:

Post a Comment