It was why the girl he'd kissed up against the wall had black hair instead of blonde, and those perfect, heavier-than-the-world fingertips.

It was why he'd been remembering another's life.

It was his punishment, to become Blackfeet, to be Piegan. To live on the reservation he'd created, the situation he was already leaving behind. To replace his own life with an Indian one, and thus know firsthand the end result of his policies. An end result generations away from last Winter, just so he could see the scope of what he'd done, that it still had a traceable effect. So that, in a sense, he could be inflicting it upon himself.

Doby Saxon is a teenager living on the Blackfeet reservation that abuts Glacier National Park in Montana. Doby is a down-and-out kid in a down-and-out place: he's missing three fingers from the time he and his father tried to poach elk from the park, and his father fell from his snowmobile and died. He has a run of untold luck at a casino, then loses it all, and causes a violent scene that ends up putting his mother in jail. He fails to save his friend from overdosing in a concrete tipi; he tries to kill himself in a hundred unsuccessful ways.

But Doby is also extraordinary: he discovers a cache of letters from a white Indian agent that lived on the reservation a century ago, and then begins to see the agent in visions. Doby is torn between these two realities, and we come to learn that Doby might be the Indian agent himself, reborn as a Blackfeet Indian through a curse that condemns him to live as those he had a part in starving.

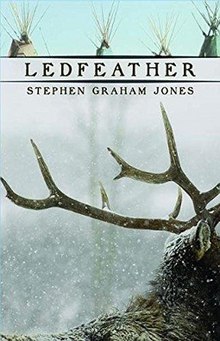

There's much to admire about Ledfeather. It's a novel with one very good idea at its heart, but it's also a novel of terrific detail and writerly skill. Unlike Moon of the Crusted Snow, which I bring up only because it seems to fit in the box of indigenous science fiction, though the context and community is much different, Ledfeather seems to understand that community life thrives in specifics. Ledfeather, among other things, is a lovingly rendered version of what is often a difficult life on the Blackfeet reservation: it gives life to casinos, game wardens, schools, hospitals, chintzy little museums, basketball courts.

But I also have to admit that I found the whole thing extremely hard to follow. Jones' novel has, if I'm counting correctly, at least four different narrative modes: 1.) first-person narratives by various people on the reservation about Doby, which ask us to piece together an understanding of him (these sections often refuse to identify clearly who the narrator is, in a way that seems self-consciously literary) 2.) the unsent letters of the Indian agent Francis Dalimpere to his wife Claire 3.) third-person accounts of the Indian agent flashing "forward" in time, 4.) second-person (!) accounts of Doby's life. I could have managed maybe two of those, but not three, and certainly not four. Ledfeather's not a long novel, but it just has one too many tricks up its sleeve, and I felt like some streamlining might have made it more readable.

As a result, I felt like the novel's many good ideas didn't land with enough emotional power for me. And they are very good: I liked especially the novel's motif of self-sacrifice, which comes in both noble and misbegotten stripes. One of the subplots of the modern narrative is that the local school's star basketball player has a terrible kidney disease, and young people from all over the reservation rush to commit suicide in order to give him their kidneys. There's kind of grim, very grim, humor that works because it sits aside other kinds of sacrifice: the Indian agent's, for example, who first kills a herd of U.S.-owned cattle for the starving Blackfeet, knowing that he'll be put in prison, and then later "sacrifices" himself by becoming Doby Saxon. Or Doby's mother, who goes to jail protecting her son in that casino fiasco. These stories of self-sacrifice are linked by the image of the elk that Doby and his father go hunting:

The story, too, it was a joke mostly, like all of Earl's stories, was that one time an elk had found a white man lost and dying in the storm, and they'd talked to each other, and finally the elk, because it knew the man needed to live, to be warm, it took pity and laid on its side and let the man cut it open and crawl inside, and stay warm like that even though the snow piled up all around them for days and days and even years, only when the man finally crawled out again, everything was different, because that elk you crawl into, it's not the same one you crawl back out of, right?

In the end, Ledfeather is a hopeful kind of book, one that shows that nobility and selflessness are alive on the reservation, and that even has hope for white people, like Dalimpere, who think to make amends. So much so that you might forgive it for asking a little too much of its readers.

No comments:

Post a Comment