And the Queens themselves, who emerge in their hundred of hundreds, must possess strength and skill and cunning and tenacity to survive more than a very few moments after successful fecundation, let alone start a nest. The time in the blue sky, the dizzy whirling in the gauzy finery lasts only a few hours. Then they must snap off their wings, like a young girl stepping out of her wedding veils, and scurry away to find a safe place to found a new nest-colony. Most fall prey to birds, other insects, frogs and toads, hedgehogs and trampling humans. Few indeed manage to make their way again underground where they will lay their first eggs, nourish their first brood of daughters--miserable dwarfs, fragile and slow, these early children--and in due course, as the workers take over the running of the nursery and the provision of food, they will forget that they ever saw the sun, or thought for themselves, or chose a path to run on, or flew in the midsummer blue. They become egg-laying machines, gross and glistening, endlessly licked, caressed, soothed and smoothed--veritable Prisoners of Love. This is the true nature of the Venus under the Mountain, in this miniature world a creature immobilised by her function of breeding, by the blind violence of her passions.

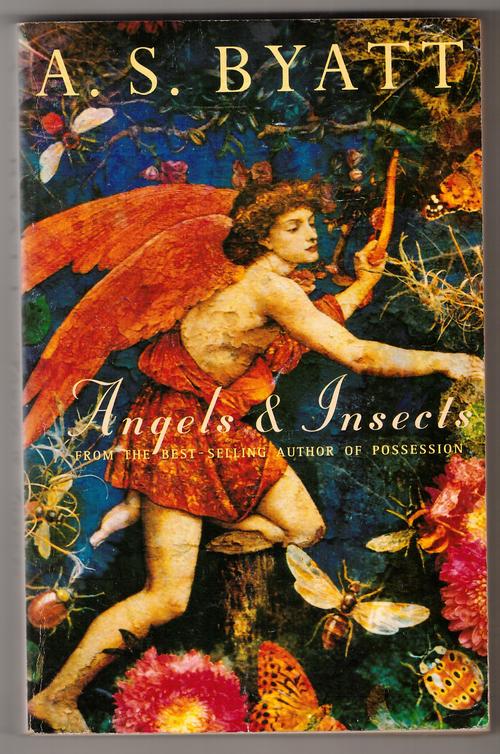

In "Morpho Eugenia," the first of two novellas that make up A. S. Byatt's book Angels and Insects, a young explorer and entomologist named William Adamson has returned to England from the Amazon. He has spent years studying and collecting, but his entire collection is gone, shipwrecked, and so he has to find shelter at the mercy of an elder collector with whom he has had an ongoing correspondence. In return for shelter, William agrees to help his benefactor, Harald Alabaster, to organize his own collection of specimens, as well as to converse with him about the arguments against and in favor of the existence of God, which Alabaster means to publish in a book. And though William is anxious to return to raise funds for a new voyage and continue his studies in the rainforest, there is a consolation prize at Harald Alabaster's estate: his beautiful daughter Eugenia, with whom he falls in love, and whom he eventually marries.

William presents Eugenia with a gift: a specimen of the Morpho eugenia, a pale-colored but beautiful butterfly from the Amazon, who happens to share her name. Much is made of the color of butterflies: they are a warning of toxicity, for one, so any time we see Eugenia in a brightly or pale colored outfit we're being asked to ponder the wisdom of William's marriage. Male insects seem to be more brightly colored than females, and surely this says something about the natural relationship between men and women? William, in his spare time, undertakes a longitudinal study of the ants around Alabaster's estate with the Alabaster children and a servant named Matty Crompton, who shares his interests in insects. The lives of ants, too, seem to provide fertile metaphors for human life. Is the ant Queen, the "glistening egg-laying machine" an image of Eugenia, who keeps pumping out children who seem not to have any resemblence to William? Are the Sanguinea ants who literally enslave ants of other species and convert them under a kind of Stockholm syndrome a metaphor for William's relationship to the Alabasters?

"Men are not ants," William says to Matty, matter-of-factly. It's a reminder that our habit of looking to the animal world to explain something about human nature is an act of anthropomorphism, that is to say, an act of projection. Although what we conclude can be unpleasant, we can comfort ourselves by looking at the animal world and seeing ourselves reflected; we can say, look, that's just the way it is. For Harald Alabaster, the social lives of insects are proof of a divine pattern he is desperate to see. Darwin's ideas have arrived to threaten cultured belief in intelligent design, and Alabaster, who is old and frail, must ward them off to assuage his own fears of death. But the animal world is incredibly diverse, and Byatt tells us that we can find anything in it, if we look hard enough. What is much harder is to really look at people: see, for instance, how William Adamson steadfastly refuses to see the way in which his assistant Matty Crompton is better suited for him than Eugenia Alabaster.

Fears of death are even more explicit in the second novella, "The Conjugial Angel." It's set among a small group of dabblers in the occult, who meet frequently to perform seances and the popular 19th century psychic practice known as "automatic writing." Each of these characters is touched by grief: a woman who has lost several infants, all named Amy; a woman trying to reach her shipwrecked explorer husband; and the sister of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who, like her brother, has spent decades dealing with the grief over the drowning death of her fiance Arthur Hallam. Hallam is the subject of Tennyson's famous poem "In Memoriam A. H. H.," one of the most beautiful meditations on death in the English language. In Byatt's account, Emily, who has since remarried, has always been conflicted by the depth and fame of her brother's famous poem; she has often felt like Alfred's grief has crowded out her own, and at the same time the poem's composition and reception have kept her, and Alfred, from any sort of closure. That's emphasized when the medium, a weirdo named Sophy Sheekhy, conjures up Hallam's moldering and confused old spirit, who has been unable to "cross over" into the spirit world.

"The Conjugial Angel" would be familiar to readers of Byatt's Possession. It, too, is centered on a 19th century poet, and Byatt's reading of Tennyson is deep and thoughtful. It's a little knottier than "Morpho Eugenia," partly because it's an ensemble piece that really lacks a main character, and partly because so much of it really is a kind of literary criticism. You get the impression that it might work best for "In Memoriam A. H. H." superfans, wherever they are, but for those of us who are only passingly familiar with the poem--or like most people, not familiar at all--it's hard to shake the idea that we're missing some crucial knowledge to make the novella work. That being said, it's got some great moments, especially when it imagines a strange and colorful spirit world. But it's "Morpho Eugenia," with its Victorian gothic narrative and colorful descriptions of insects, and which looks down at the ground instead of up to the heavens, which is going to stay with me most.

No comments:

Post a Comment