To understand why people believe things that are at odds with all provable truths is to understand how we form our views about the world and the resultant world we have made together. The riotous profusion of conspiracy theories in America shows us something about being American, even about being human--about the decisions we make in interpreting the complexities of our surroundings. Over and over, i found that the people involved in conspiracy communities weren't necessarily some mysterious "other." We're all prone to believing half-truths, forming connections where there are none to be found, finding importance in political and social events that may not have much significance at all. That's part of how human beings work, how we make meaning, particularly in the United States today, now, at the start of a strange and unlikely century.

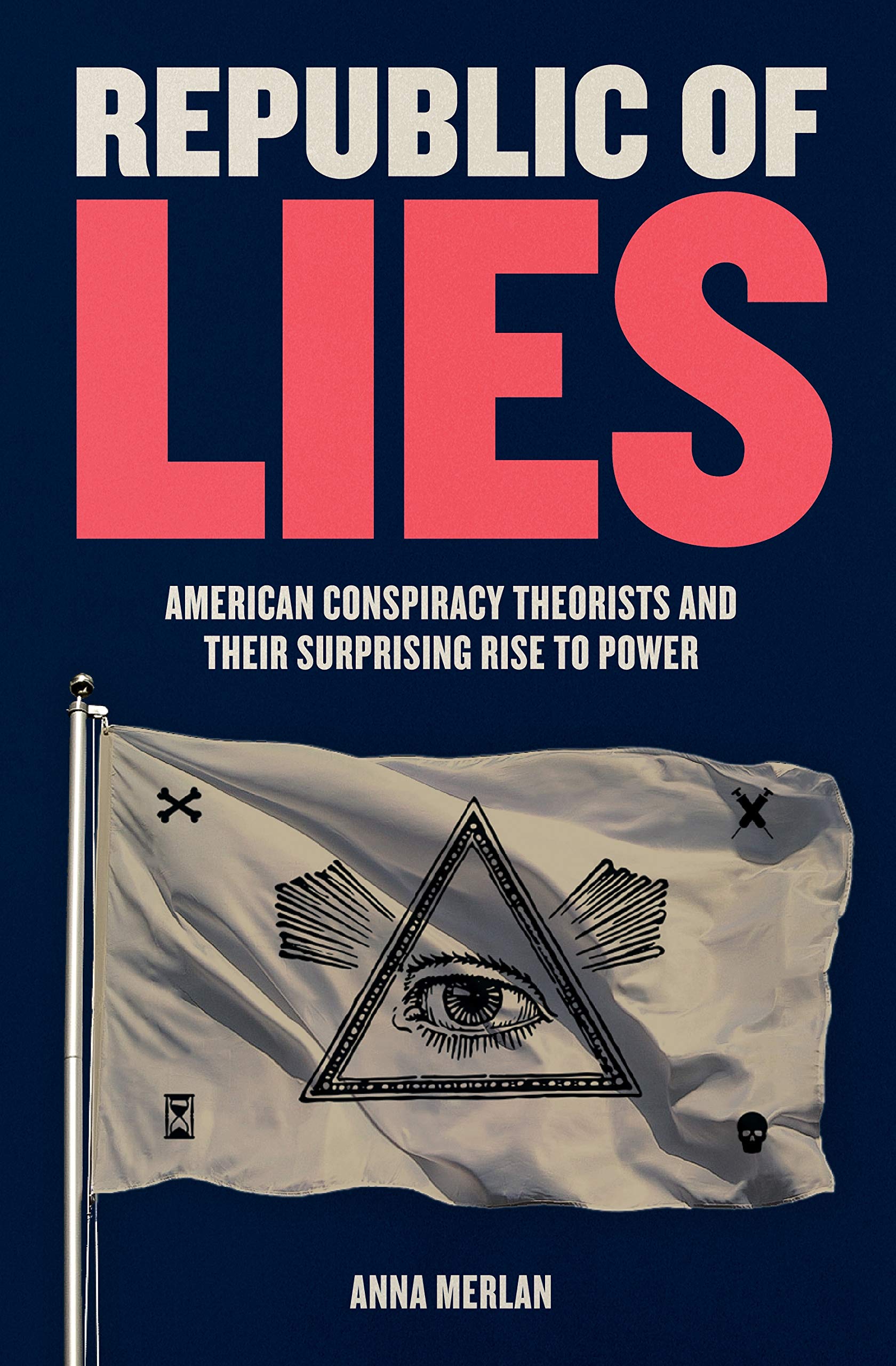

In her book about conspiracy theories, Anna Merlan makes two core observations: One, conspiratorial thinking is commonplace. It goes back long before JFK, to the very foundations of the American idea, like the early settlers who feared a sinister Native "superchief" who is orchestrating attacks on whites across tribes and over thousands of miles of frontier. And she's careful to note that conspiratorial thinking isn't always incorrect: The MKUltra program, for example, is just one crazy conspiracy--in this case, the allegation that the CIA was experimenting with LSD as a mind-control drug on unsuspecting people--that turned out to be true. Other conspiracy theories, like the one that says the government introduced cocaine into black communities to destroy them, are very likely to be untrue, but it's not hard to see why one would believe them, given the other terrible things the government has perpetrated on those communities. Sometimes, conspiratorial thinking is a rational response to the ways in which ordinary people are alienated from power.

The second core observation is that, despite their commonness, our current political moment is unique. Never before in the history of the United States has traditional political power been so wedded to conspiracy theory, and wielded by the very powers who are traditionally the object of its suspicion. Merlan's examples include Pizzagate, the insane theory that the politically powerful, especially the Clintons, were using the basement of a DC-era pizza chain to operate an international child molestation ring. You might not find President Donald Trump tweeting about Pizzagate, but he sure is happy to lead the "Lock her up" chants that rely on its continued survival. Trump's modern political career, of course, is rooted in the conspiracy theory of birtherism, and his "some are saying" allusions continue to pay political dividends. You only have to look to his recent allegations that doctors and mothers are executing live children after birth. We live in an era of accelerated information and disinformation, which has facilitated the rise of conspiratorial power.

One of my takeaways from Merlan's book was that it was all depressingly familiar. The chapters are a laundry list of conspiracy theories, from the stupid to the pernicious, that continue to be litigated on Twitter every day: Pizzagate, false flag attacks at Sandy Hook and Parkland, the murder of Seth Rich. I was almost relieved to read about a conspiracy theory I had never heard of: redemption theory, which maintains that the federal government backs the dollar by depositing a specific amount of money into the Federal Reserve for each birth, and that with a mastery of arcane and complex tax law, a person can legally withdraw and use their specific funds. This particular chapter is heartbreaking--it tells the story of a couple of redemption theorists who end up charged with tax evasion and fraud, and who continue to believe in it even as they face bankruptcy and prison time. And yet, the familiar rears its ugly head: redemption theory turns out to be a pet cause of Oregon militia leader Ammon Bundy, whose illegal occupation of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge in 2015 was gleefully taken advantage of by all sorts of mainstream right-wing ghouls.

Another takeaway: Do you know who pops up in every single one of these chapters? The one person who seems to be involved with UFOs, Pizzagate, false flags, vaccine anxiety, and secret cancer-curing supplements? You'll never guess:

It's sort of amazing. The man is everywhere. Republic of Lies made me think that we haven't yet reckoned with just how crucial a figure Alex Jones is in our modern political landscape, perhaps not as an agent but a representation of our conspiracy-loving id, and the way it gets entangled with real political power and financial gain.

Republic of Lies might be sobering for the reader who hopes that the Trump presidency ends with the nation, collectively, coming to its senses. The conspiracy theories themselves are here to stay. But maybe, before it's too late, we might learn how to distinguish not just between fact and fiction, but power and powerlessness, and stop letting those who have power convince us that it's the powerless who are conspiring against them. It would also be nice if we could convince people that vaccines are safe and apricot pits can't cure cancer. One day.

No comments:

Post a Comment