Romy Hall is serving a lifetime sentence for killing a disabled man--her stalker. She killed him because she was afraid for her son, Jackson, and in the blackest of ironies, it's this act that means she'll be separated from her son forever. Not just physically, but legally, spiritually; her parental rights are terminated, meaning she doesn't have a right even to know where he is or if he's all right. This is perhaps the greatest indignity of her prison sentence, but it's not the only one. How about the time when, upon arriving at prison for the first time, she helps deliver a baby despite the explicit orders of prison guards, and ends up in "ad seg," solitary confinement? You'd be hard pressed to find a more explicit symbol of the way that the carceral state robs the dignity of women in particular.

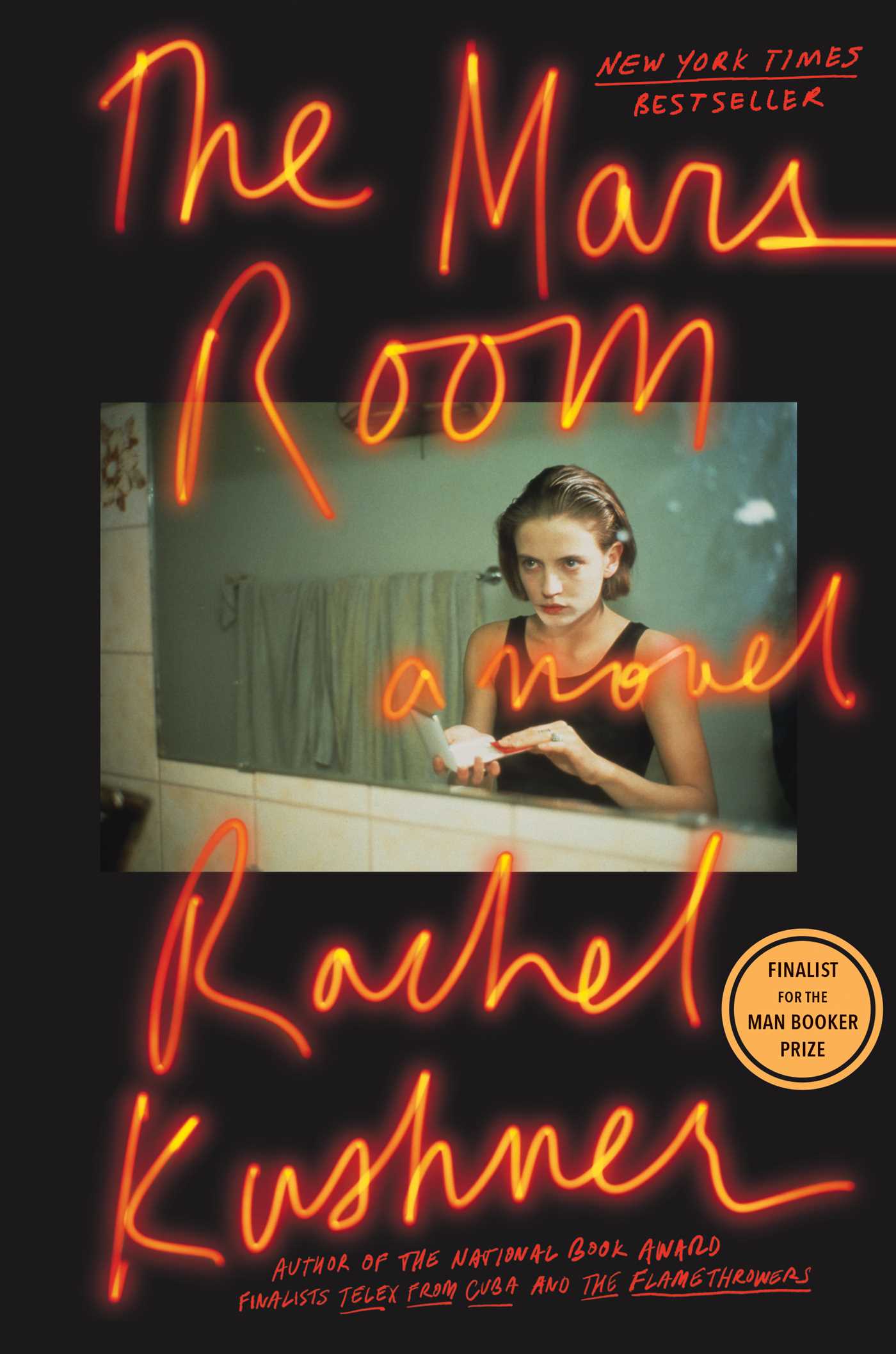

It's hard to read The Mars Room, Rachel Kushner's new novel, without thinking about Orange is the New Black. I imagine that for most people, including me, the Netflix show is the first and only artistic depiction of women's prison they've known. Like Piper Chapman, Romy is more literate than her cellmates (look at her chat with the prison tutor about Denis Johnson's Jesus' Son!), a fact that's meant to build a stronger sympathy with the reader, who is, after all, a reader, and to provide context for Romy's highly attenuated eye. Here, for example, is what she sees in a mattress lying against a tree:

We were at a stoplight past the off-ramp. Outside the window, a mattress leaned against a pepper tree. Even those two things, I told myself, must go together. No pepper trees, lacy branches and pink peppercorns, without dirty old mattresses leaned up against their puzzle-bark trunks. All good bound to bad, and made mad. All bad.

But unlike Piper, Romy really does come from poverty. She's raised in a down-at-heels part of San Francisco, peopled by junkies and pimps, feeling miles away from the technocrats and the hippies of popular vision. Though the novel begins with Romy's transfer to the Stanville prison, about half of it is filling in this back story. She's exposed to violence at a young age, and learns early on what men will do to women they have power over, even twelve-year olds. She's a stripper at the title club, but not a stripper with a heart of gold, or a cartoon. Like her coworkers, she's someone who's learned to exploit the broken operation of the male gaze to her own benefit, even as it seeks to victimize her in ways large and small.

Does Romy deserve to be in prison? Certainly the account of her crime, which appears at the end, casts into doubt the urgency of her claim to self-defense. But Kushner is interested in other, more complicated questions: for example, how does the carceral state use the narrative of absolute responsibility to minimize the context that makes up the lives of those it punishes? We can't understand Romy's crime without the context of her stalker's stalking, which only makes sense in the context of the broader ways in which men punish women in America, a dynamic that the prison only exacerbates. Kushner explores these questions subtly and thoughtfully, but tips her hand a little in the thoughts of Gordon Hauser, the prison tutor, who thinks:

The word violence was depleted and generic from overuse and yet it still had power, still meant something, but multiple things. There were stark acts of it: beating a person to death. And there were more abstract forms, depriving people of jobs, safe housing, adequate schools. There were large-scale acts of it, the death of tens of thousands of Iraqi civilians in a single year, for a specious war of lies and bungling, a war that might have no end, but according to prosecutors, the real monsters were teenagers like Button Sanchez.

Button Sanchez committed an awful crime, beating an Asian student to death. Hauser is convinced she didn't see him as a person, which hardly exonerates her. But the prison only doubles down on what Hauser sees as the root cause of violence, denying Button's personhood. It's a little on the nose--on the button, maybe--to compare the Stanville prison to the Iraq War, but the point is a solid one. Button's act of violence pales in comparison to the systemic violence that is incarceration, and in America we fail to reckon with that measurement on a daily basis. "It added new harm to old," Hauser writes of the prison system, "and no dead person ever came back to life that he had heard about." The brightly-colored sisterhood tropes of Orange is the New Black, even though it often makes sharp criticisms, lack the essential tonal darkness that our prisons deserve, and The Mars Room delivers.

Kushner's writing is full of excellent, powerful detail. Here's just one little bit that I liked about a totally minor character:

He only left the house himself one evening a week, Sundays, when he worked as a volunteer security guard at the Red Cross. He made a big deal about it. Always took a briefcase with him, and said it held important documents that he needed to study for his next Daytona run. It wasn't really a briefcase. It was the emptied container for a backgammon set. Once, Sammy opened it. It was filled with candy bars.

It's funny, it's real, it's specific. What a terrific image is: the backgammon set full of candy bars. She does that throughout, sketching each individual life with a careful and empathetic eye, and a sense of how absurd life can be. During the long bus ride to the prison, one prisoner waxes poetic about how they're going to miss the Bloomin' Onion at Outback.

But as a whole, the narrative sags. It takes a hundred pages just to get Romy off the bus and into the prison. The novel is peppered with accounts from other characters, sometimes in the first person, sometimes in the third: her cellmate, Sammy, the crooked cop, Doc, in a men's prison somewhere, and especially Gordon, the tutor. Kushner also splices in some sections from Ted Kaczynski's journals. And while I think I get why--Gordon lives isolated in the mountains, like Kaczynski; Romy imagines those same mountains are a kind of Eden just out of reach; neither Gordon nor Kaczynski can understand isolation in the way Romy can because their isolation is her Eden, etc., etc.--it seems like a lot of pages to make what seems like a convoluted observational loop. The Gordon sections are especially frustrating, because as interesting as he is as a character, his presence ends up a narrative dead end for Romy. As a result, the time spent in the actual prison with Romy is relatively short.

The end gives a flash of narrative drive, but it doesn't quite ring true, in a novel that spends so much time milling about in the fine details. Forget it. Life sentences don't have narrative drive. As Kushner writes, "[L]ife does not go off the rails because it is the rails, goes where it goes."

No comments:

Post a Comment