In early autumn the farm recruiters arrived to sign up new workers, and the War Relocation Authority allowed many of the young men and women to go out and help harvest the crops. Some came back wearing the same shoes they'd left in and swore they would never go out there again. They said they'd been shot at. Spat on. Refused entrance to the local diner. The movie theater. The dry goods store. They said the signs in the windows were the same wherever they went: 'No Japs Allowed.' Life was easier, they said, on this side of the fence.

The Japanese internment during World War II may be the least-discussed major shame in American history. In spite of resistance from some fronts, there is at least a general recognition that slavery was bad and we shouldn't have killed all the the Indians. The Japanese internment, on the other hand, I didn't even learn about in high school. Right-wing shill Michelle Malkin wrote a book in defense of internment, no doubt hoping it would spur a smililar movement toward her own group non grata, Muslims. And Asians, now treated as a model minority by the "I'm not racist but" crowd, are often spoken of as though their American experience has been smooth sailing, never mind that even high profile figures like George Takai were actually in these camps. This isn't ancient history.

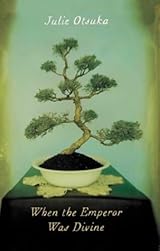

I'm not confident I've read anything about the internment in the course of Fifty Books, and When the Emperor Was King did a good job whetting my appetite for more. It's a terse, unsentimental little novel that doesn't even name its characters even as it follows them through the arrest of their father, their own move to and life in an internment camp, and their eventual return home, where they are finally, after several years, reuinited.

When I say this book is unsentimental, it's no joke. The first section--the book is split into five--follows the unnamed mother as she prepares their house for their indefinite absence. Some of the preparations are benign--packing things aways, making sure the faucets are off. Others are more chilling and speak to uncertainty and permenance of their dislocation, like when we follow her to the store where she purchases a new shovel with which to kill and bury the family dog. Does this make her sad? Angry? Resigned? We're never told, just as the children are never told why White Dog isn't coming when she's called.

The train ride to the camp and life in the camp itself is endless monotony punctuated by the terror of being completely powerless and surrounded by those who are indifferent. The girl thinks she seems some humanity on a guard's face, but the reader has no reason to think its real. Shades are kept low lest a passby lob a brick through a window upon realizing the bus is full of 'the enemy'.

And finally, the family returns home, to a house that's been destroyed by tenants who paid no rent or respect; they are greeted, or not greeted, by old friends who now see them as the enemy; they sleep every night with the threat of vandalism, arson, or worse; and they wait for their father to come home. But when he does, he's not the man they remember:

As the days grew longer our father began spending more and more time alone in his room. He stopped reading the newspaper. He no longer listened to Dr. IQ. with us on the radio. "There's already enough noise in my head," he explained. The handwriting in his notebook grew smaller and fainter and then disappeared from the page altogether. Now whenever we passed by his door we saw him sitting on the edge of his bed with his hands in his lap, staring out through the window as though he were waiting for something to happen. Sometimes he'd get dressed and put on his coat but he could not make himself walk out the front door.

In the evening he often went to bed early, at seven, right after supper - 'Might as well get the day over with' - but he slept poorly and woke often from the same recurring dream: It was five minutes past curfew and he was trapped outside, in the world, on the wrong side of the fence. "I've got to get back,' he'd wake up shouting.

'You're home now,' our mother would remind him. 'It's all right. You can stay.”

That "You can stay" breaks my heart. It communicates so much that has been surpressed in the book and in history itself. The heartbreak of disassociation, the despair of rejection, the pointless brokenness resulting from racism and fear. And it's a message that can't help but resonate now in the age of Trump, with Muslim bans, mosque bombings, "the wall", and the desire to Make America Great Again--when the question that really needs to be asked is, "Was there ever a time when America was really great?" The least of these would probably answer "no." But maybe instead of repeating history, there is a faint hope that we can learn.

No comments:

Post a Comment