'Loss!' it said. 'That's what she was to me, you know: she was the loss of her even when she was apparently the finding of her, the having of her. And I was the same to her, I was her the loss of me. We were the two parts of a complementarity of loss, and that being so the loss was already an actuality in our finding of each other. From the moment that I first tasted the honey of Eurydice I tasted also the honey of the loss of her. What am I if not the quintessential, the brute artist? Is not all art a celebration of loss? From the very first moment that beauty appears to us it is passing, passing, not to be held.'

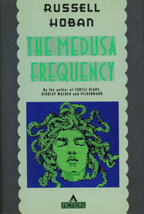

Herman Orff makes a living turning classic novels into comic books, and at night he tries to write his third novel. He has writer's block; he's hung up with the loss of his ex Luise, who left him years ago. He visits a London shop advertising a solution for his problem, and they give him a brief electrocution, after which he begins to see the severed head of Orpheus in the place of various spherical objects around the city.

Hoban's version of the Orpheus story--if I can try to compress what's so loose and variegated in the novel--is a story of the connection between art and loss. Orpheus tells the story of his creation of the lyre, which was first made out of a tortoise shell, necessitating the murder of the tortoise:

The tortoise was in my left hand and my knife was in my right; my idea was the tortoise-shell empty and two posts and a yoke and some strings for a kind of little harp with the shell as a soundbox. The man's eyes were still on me, his wide-open eyes; almost I wanted to use the knife on him to make him stop looking at me. He let his hands drop to his sides when I cut the plastron loose and dug the body out of the shell, ugh! what a mess and my hands all slippery with blood and gore. The entrails were mysterious. I think about it now, how those entrails spilled out so easily when I made an emptiness for my music to sound in. Impossible to put those entrails back.

The creation of art, then, is inseparable from the experience of loss, the distance we feel from those we have loved. Not a way of coping, Hoban insists, but very nearly the experience of loss itself. Into this central conceit Hoban ties a shaggy collection of symbols and motifs--the head of the Medusa, something called the "world child," Vermeer's Lady with a Pearl Earring. In one memorable sequence, the hero Herman Orff ("her man, Orpheus"--LOL) boards a boat to Holland to see the painting in real life; but it's on loan in America so he's forced to contemplate its absence. Hoban shares a tendency with Muriel Spark, I think, to overload slim narratives with images and ideas so that you're prevented from really seeing the whole. But as Hoban writes about writing, "Where was the beginning of anything, how could I draw a line through endless cause and effect and say, 'Here is page one?'"

With all that cramming the fewer than 150 pages of the novel, it's surprising that Hoban is able to make it as funny as it is. Hoban has a field day with the comic scenarios in which the head of Orpheus appears, in place of a boulder, or a globular street lamp, or half a head on a plate where half a grapefruit ought to be. (Orff runs home trying to keep in the brains.) I've been struck by how different Hoban's books are from each other, but here I see common links with the gleeful pantheistic personification of Kleinzeit, and the sad-sack lonely Londoners of Turtle Diary. (One wonders what Orpheus, the turtle-killer, would think about the couple in that novel releasing their inscrutable turtles into the wild.) But like those novels, The Medusa Frequency is truly, unforgettably, weirdly unique.

No comments:

Post a Comment