What is jealousy? Jealousy is to say, what you have got is mine, it is mine, it is mine? Not quite. It is to say, I hate you because you have got what I have not got and desire. I want to be me, myself, but in your position, with your opportunities, your looks, your abilities, your spiritual good.

What is jealousy? Jealousy is to say, what you have got is mine, it is mine, it is mine? Not quite. It is to say, I hate you because you have got what I have not got and desire. I want to be me, myself, but in your position, with your opportunities, your looks, your abilities, your spiritual good.Chris, like any of us, would have been astonished if he had known that Rowland, through jealousy, had thought with some tormented satisfaction of Chris dying in his sleep.

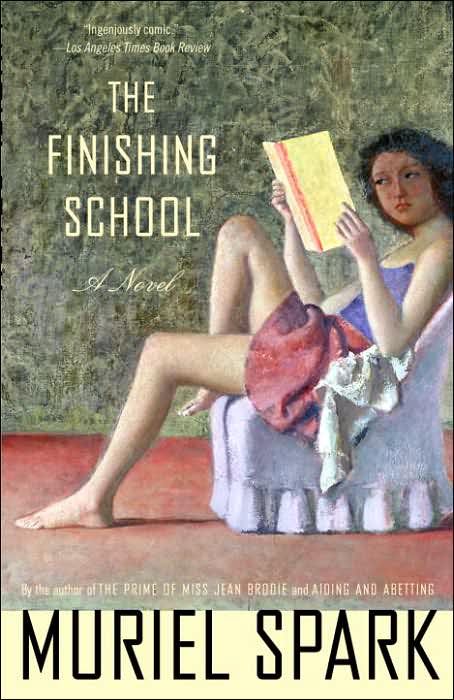

I remember someone once said of Spoon's Britt Daniel that once a song has been recorded, he takes out every track that isn't necessary, and then takes out one more. I kind of feel the same way about Muriel Spark, whose books are notable for their brevity and sparseness. The Finishing School was Spark's last book before her death, and it's so caustic, and so spare, that it gives the impression of being a long-winded joke.

The Finishing School is a chronicle of jealousy: Rowland Mahler runs a third-rate school with his wife, Nina, in Lausanne, Switzerland (though it moves every year that the Mahlers might escape the debt they rack up in each city). Their prize pupil is a 17-year old named Chris Wiley, who is composing a novel about Mary, Queen of Scots. It's very good, but the novel that Rowland is writing is not, and his envy of Chris' talent nearly drives him insane.

Eventually, Rowland escapes to a monastery in order to flee his destructive feelings, but is beckoned back to the school by Chris, who thrives off of Rowland's jealousy and can't finish his novel without it. In a neat bit of parallelism, Chris' book is about jealousy as well: The jealousy of Queen Mary's husband Lord Darnley toward her favorite courtier, David Rizzio, which leads to Rizzio's murder. That Rowland's relationship with Chris may also lead to murder is strongly suggested, but there is also a strange sexual element to Rowland's obsession, leading Nina and the other students to question Rowland's sexuality. This is not a particularly subtle element of the story, and Spark makes it less so by noting in the epilogue that a newly divorced Rowland marries Chris in a same-sex affirmation ceremony.

Spark's books tend to be about the relationship between the author and the character, and The Finishing School is no different. Rowland suggests in his creative writing class that a good author allows his characters, like real people, to surprise him, which Chris refutes with an idea cribbed almost verbatim from Nabokov: "Nobody in my book so far could cross the road unless I make them do it." And yet, Chris is writing a historical novel, and purposely distorting historical fact, consciously engineering actions and interactions that Mary, Darnley, and Rizzio could not, or would not have perpetrated. In contrast, Rowland cannot seem to control even his present; his attempts to convince Chris to give up his novel are fruitless and transparent. His writer's block mirrors his inability to affect real people, including himself.

Of course, Spark cribs from Nabokov because she's playing the same game that Nabokov loved to play: pointing out that all this business about control and agency is nonsense; it is the author who is pulling the strings. Spark is God, and no one could cross the road unless she makes them do it.

From the school setting to the underlying theme, The Finishing School reads like an update on The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. At its worst, it could be a parody of that novel. The Finishing School is infinitely less satisfying than Jean Brodie partly because it seems redundant, and partly because Rowland is infinitely less interesting. Brodie is a sham and a fraud, but she is adored by her students who fail to see through her. Rowland is pathetic, and blatantly so; his neurosis over Chris' novel is clear to everyone he interacts with. For this reason, Spark's satire at times seems unnecessarily cruel.

In this case, Spark's trademarks seem to work against her. She dismisses her characters summarily and disdainfully, but we never have a chance to sympathize with them, or even invest emotionally or intellectually in their success or failure. A big, fat book like War and Peace or Infinite Jest seems to justify its existence by its sheer presence; The Finishing School is so slight, and so redundant, that it makes one wonder why Spark bothered writing it at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment