Could a man ride home in the rear smoker, primly adjusting his pants at the knees to protect their crease and rattling his evening paper into a narrow panel to give his neighbor elbow room? Could a man sit meekly massaging his headache and allowing himself to be surrounded by the chatter of beaten, amiable husks of men who sat and swayed and played bridge in a stagnant smell of newsprint and tobacco and bad breath and overheated radiators?

Could a man ride home in the rear smoker, primly adjusting his pants at the knees to protect their crease and rattling his evening paper into a narrow panel to give his neighbor elbow room? Could a man sit meekly massaging his headache and allowing himself to be surrounded by the chatter of beaten, amiable husks of men who sat and swayed and played bridge in a stagnant smell of newsprint and tobacco and bad breath and overheated radiators?Hell, no. The way for a man to ride was erect and out in the open, out in the loud iron passageway where the wind whipped his necktie, standing with his feet set wide apart on the shuddering, clangoring floor-plates, taking deep pulls from a pinched cigarette until its burning end was a needle of fire and quivering paper ash and then snapping it straight as a bullet into the roaring speed of the roadbed, while the suburban towns wheeled slowly along the pink and gray dust of seven o'clock. And when he came to his own station the way for a man to alight was to swing down the iron steps and leap before the train had stopped, to land running and slow down to an easy, athletic stride as he made for his parked automobile.

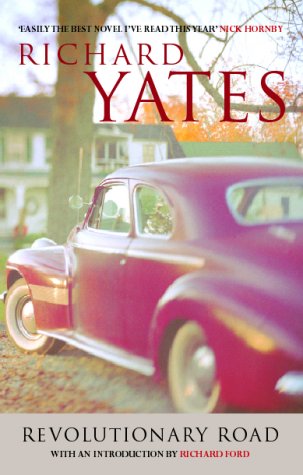

Revolutionary Road is a desperately sad book, and sadder for its realism: Here is the story of Frank and April Wheeler, a young, good-looking couple with small children living a plain life in the Connecticut suburbs outside of New York City. Frank and April are bright and well-educated, and both yearn for something more than a life as excruciatingly ordinary as the one they have, and rightfully so: Yates' depiction of the suburbs is almost paralyzing in its dullness. And yet at the same time, Frank and April are so cavalier and spiteful about their surroundings, even when trying not to be, they come across childish, and their aspirations lead them to quarrel and ultimately into tragedy.

What is horrifying about Revolutionary Road is that Frank and April are more everyman and everywoman than they suspect; or at the very least everyman-or-woman-who-might-pick-up-this-novel. Their suspicions of suburban life walk a narrow line between legitimacy and egoism, falling alternately into one realm or the other and exposing how similar the two can be. To indict Frank and April is to indict anyone who has entertained, as Frank and April do, the notion of pulling up stakes and moving to Europe (and admit it--haven't you?).

Frank and April decide to do exactly that, jobs and children be damned, and we must wonder whether they would have gone through with it if not for a single event that complicates things mightily (and which I shall not reveal). The scuttling of this plan leads to the widening of the already apparent rift between the two, to the escapism of adultery, and finally serves to cast a light on the futility, emptiness, and frustration that characterize suburban life. The final act is unbearably gruesome, but grimly appropriate.

I didn't love Revolutionary Road; it was too bleak for me. I can handle a book like The Road, which is horrifying and grotesque but takes place in a world that seems far removed from our own, but the world which we do inhabit has only become more like Revolutionary Road in the past fifty years. Yikes.

N.B.: Christopher Hitchens' recent review for the Atlantic Monthly is excellent.

No comments:

Post a Comment