We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath ... a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath ... a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.--"The Futurist Manifesto," F.T. Marinetti

Beneath the data strips, or tickers, there were fixed digits marking the time in the major cities of the world. He knew what she was thinking. Never mind the speed that makes it hard to follow what passes before the eye. The speed is the point. Never mind the urgent and endless replenishment, the way data dissolves at one end of the series just as it takes shape at the other. This is the point, the thrust, the future.

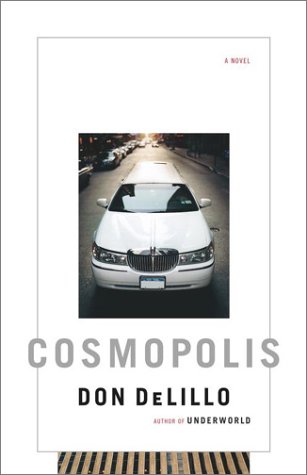

--Cosmopolis, Don DeLillo

It struck me while reading Cosmopolis that perhaps if Marinetti, the founder of the Italian mindfuck philosophy that was Futurism, were alive today he would love this book. Marinetti wrote his manifesto in 1909, not long after the invention of the automobile, and one can only imagine what he would say if he could see today's cars, which make the racecars of one hundred years ago look tortoise-slow.

On the other hand, it may not be the automobiles which capture his imagination. In Cosmopolis, Don DeLillo places his anti-hero, multi-billionaire Eric Packer, in an automobile, one of the world's finest stretch limousines, but the power and speed of the vehicle is wasted in the novel-length crawl across the width of gridlocked Manhattan. It takes Packer an entire day (and novel) to accomplish his goal, which is to drive crosstown and get a haircut. On this interminable journey he is an observer to a presidential motorcade, a rapper's funeral, and a violent process, and a participant in a small handful of sexual escapades. All this traveling at what must be a fraction of a mile per hour!

But that is not to say that the limousine does not embody Marinetti's love of speed--though the limousine may be nearly stationary, it is the conduit through which Packer can monitor all facets of his global finance empire, through which information moves at speeds which would give Marinetti wet dreams.

In fact, information in Cosmopolis moves so quickly that it surpasses even real time. Take the security monitor inside the limousine, for instance, that shows Eric his actions a split second before he even commits them. Cosmopolis is a messy, sprawling novel (even at a slim 200 pp.) but I think that it can be whittled down to this idea, that in our modern era we live on the edge of precipice so razor-thin that we are in danger of falling off.

The Futurists wished to destroy the museums, which they considered graveyards; true art, they felt, must be continually and violently replenished and started anew. Cosmopolis seems to argue that we live in the Futurists' ideal world, that the tides of progress have moved on without us, past all human control. Packer's other mission during his limo ride, besides the haircut, is to pursue a bet against the yen, which despite his best efforts, rises impossibly. By the end of the novel, in a matter of hours, Packer is penniless. This, DeLillo says, is our reality: fortunes amassed and lost in afternoons, and getting faster all the time. As Marinetti says, "Time and Space died yesterday." And as the things that Marinetti cherished--the automobiles, the guns--seem almost antiquated to us, so Cosmopolis forces us to face our own hurtling toward obsolescence.

I think perhaps that Marinetti was born one hundred years too late. Cosmopolis is the ultimate Futurist novel, but also quintessentially 21st-century; it is so cutting-edge that it edges beyond even postmodernity. But this also nurtures, and perhaps necessitates, its biggest flaw: a severe lack of humanity. The awesome James Wood, writing for the New Republic, notes that "Eric is really no more than a vessel for theory; he is given not thoughts but meta-thoughts." How true. Here is a novel with much to say, but at times seems so drunk on its ideas that it forgets that ideas are only as relevant as the people they impact.

I struggled with this--after all, isn't this the point of it all, that the human being has become as passe as the Sony Walkman? But I remember DeLillo's White Noise, a novel that managed to break through the ominous haze of turn-of-the-century paranoia and find two people simply scared shitless of dying. Where White Noise had power, Cosmopolis has portentousness.

And besides, isn't the Futurist ideal fundamentally flawed? I recall a conversation I once had with an Italian professor of mine who noted that though the Futurists believed that mankind would become more and more like the technology they created in the automobile, in truth la macchina e stata humanizata--the automobile has become humanized. Though DeLillo taps into an essential modern fear about technology run amok, the fact is that our creations are becoming more and more like us instead of the other way around. Though we may feel obsolete, it cannot be ignored that those feelings are ours; our machines and software have no opinion.

DeLillo comes around toward the end of the novel, when Packer, in a plot point I've neglected to mention, comes face to face with a would-be assassin. Face-to-face with the barrel of a gun, Packer recalls that he'd "always wanted to become quantum dust, transcending his body mass, the soft tissue over the bones, the muscle and fat. The idea was to live outside the given limits, in a chip, on a disk, as data, in a radiant spin, a consciousness saved from void."

There, confronting death like the protagonists of White Noise, Packer comes to realize from what stuff he really is made:

The things that made him who he was could hardly be identified much less converted to data... So much come and gone, this is who he was, the lost taste of milk licked from his mother's breast, the stuff he sneezes when he sneezes, this is him, and how a person becomes the reflection he sees in a dusty window when he walks by. He'd come to know himself, untranslatably, through his pain... His hard-gotten grip on the world, material things, great things, his memories true and false, the vague malaise of winter twilights, untransferable, the pale nights when his identity flattens for lack of sleep, the small wart he feels on his thigh every time he showers, all him, and how the soap he uses, the smell and the feel of the concave bar make him who he is because he names the fragrance, amandine, and the hang of his cock, untransferable, and his strangely achy knee, the click in his knee when he bends it, all him, and so much else that's not convertible to some high sublime, the technology of mind-without-end.

6 comments:

This review was better than the first third of the book. Good work.

Oh, and that was brent.

I was going to use the line "hurtling toward obsolescence" in my review of The Tale of Despereaux, but I couldn't work it in.

Have you seen the trailer for the movie, Carlton? It looks pretty excellent.

I haven't seen the trailer. I am know that I am going to watch the film, so I am actually trying to avoid seeing it.

I did see a couple of still images, and the animation looks superb.

So I read "The Futurist Manifesto" a few days ago...Crazytown.

Post a Comment