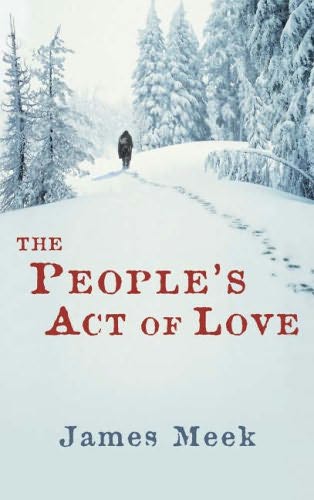

I got nervous when I saw Brent had finished another book, because Lord knows I can't have him tied with me. So I hurried to finish my current book, The People's Act of Love.

I got nervous when I saw Brent had finished another book, because Lord knows I can't have him tied with me. So I hurried to finish my current book, The People's Act of Love.Here's a synopsis as best I can write: A mysterious man named Samarin appears in the Siberian town of Yazyk, which is populated by a sect of Christians who castrate themselves in order to keep themselves from sin. Samarin claims that he's escaped from a gulag called the White Garden, and has been followed by a cunning murderer named the Mohican who wants to eat him. Meanwhile the "widow" Anna Petrovna who has followed her castrate husband to Yazyk takes an interest in Samarin, which angers her lover Lieutenant Mutz, second-in-command of a troop of Czech soldiers who have been marooned in Yazyk thanks to the Russian Revolution and live in fear of an imminent attack by Red factions. It's like a crazier version of Dr. Zhivago.

Whew. There's a lot to love about this book, like that strange plot (which borrows the tales of the castrates and stranded Czechs from actual historical sources), and the metaphorical scope of the novel, which deals with the nature of faith and sacrifice. Anna Petrovna hates her former husband for the faith that made him castrate himself, and all manners of faith indiscriminately, including Communism. In Samarin, a many-faced man and ubermensch who feels he above all notions of right and wrong, she faces the logical conclusion of her hate. Meanwhile, her castrate husband, Gleb Balashov, must deal with the irrevocable destruction of the promise he made to her in marriage--lots of complex feelings and storylines in there.

But there were a few things about this book that bothered me, as well. For a book that centers itself around the contrasts between characters, they can be nebulously characterized. The thing that bothered me the most is that they all tend to speak in the same metaphysical, disjointed language, which really prevents the characters from popping out. There's a passage in which Balashov writes to Anna Petrovna, "I am a plain writer," and then goes on to write, "They had something of another world about them; smooth skin and soft voices and ageless faces." Sometimes overly thought-out dialogue is worse than dialogue which isn't thought out at all. I like this book, but given the choice I'd just read Dr. Zhivago again.

No comments:

Post a Comment