The protagonist of the first story in Otessa Moshfegh's collection Homesick for Another World, "Bettering Myself," is a teacher at a Ukrainian Orthodox school in the East Village who cares more about nursing her drinking problem than her teaching. The protagonist of "Dark and Winding Road" is a disaffected middle-aged man who has run off to his family's cabin to punish his pregnant wife, where he gets drunk and psychically tortures his brother's girlfriend, an unexpected guest. The protagonist of "An Honest Woman" is a New Yorker who spends all summer "slumming" it in an upstate town full of people she despises. Oh, she also has a drug and alcohol problem.

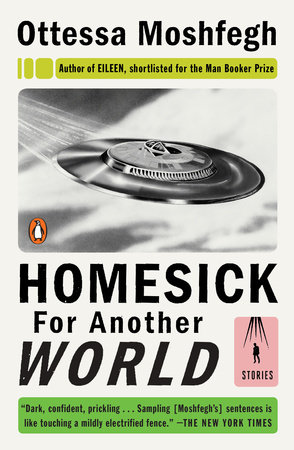

The characters in Homesick for Another World reminded me most of Denis Johnson, another short fiction writer with a passion for lowlifes and reprobates. But in Jesus' Son, Johnson has a powerful empathy for the junkies he writes about: he seems to believe that their position at the fringes of society gives them a kind of saintliness, like holy fools. Moshfegh, by contrast, seems to hate the people she writes about, who abuse not only substances but other people. I have never been the kind of person who believes a protagonist needs to be sympathetic, but I often found myself repulsed by the sourness of the people in these stories. I especially hated the character Takashi in the mercifully brief "The Locked Room," a violin prodigy who's described as mutilating himself and puking everywhere to shock people. Yet, the same strategies work in Moshfegh's novel Eileen, which is also about an aimless, needy drunk--maybe because Moshfegh has more time and room to explore the sources and nuances of the character's dissolute personality. Or because it gives the reader time and room to become attached, despite it.

The best stories in Homesick for Another World are the ones that trade in the junkies and lowlifes for good people. I really enjoyed "No Place for Good People," about a retired man who takes a part time job caring for developmentally delayed adults at a daycare facility. The plot is simple--he takes three of them out for a birthday party, but the Hooters one of them has his heart set on has been torn down and replaced with a Friendly's--but the three are drawn with empathy and respect, and the struggle of the protagonist to do right by people who can't and won't understand his intentions is compelling. I also really liked "Nothing Ever Happens Here," about a handsome but untalented man trying to make his break in Hollywood, and the kindly Jewish landlady who takes him under her wing. Another, "The Surrogate," is about a woman who takes a job pretending to be the vice president of a business, and who is invited into a kind of makeshift family with the Chinese immigrants who really run it. These stories struck me as sharing the same world as the others--one at the margins of the respectable world--but with a moral richness that the collection often lacks.

No comments:

Post a Comment