Marda West continued walking down the street. She turned right, and left, and right again, and in the distance she saw the lights of Oxford Street. She began to hurry. The friendly traffic drew her like a magnet, the distant lights, the distant men and women. When she came to Oxford Street se paused, wondering of a sudden where she should go, whom she could ask for refuge. And it came to her once again that there was no one, no one at all; because the couple passing her now, a toad's head on a short black body clutching a panther's arm, could give her no protection, and the policeman standing at the corner was a baboon, the woman talking to him a little prinked-up pig. No one was human, no one was safe, the man a pace or two behind her was like Jim, another vulture. There were vultures on the pavement opposite. Coming towards her, laughing, was a jackal.

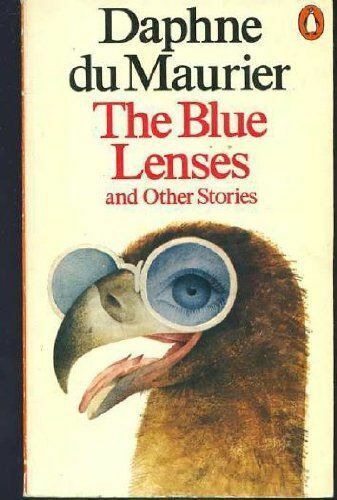

I could have sworn Daphne du Maurier's story "The Blue Lenses" was the basis for an episode of Twilight Zone, but that doesn't actually seem to be true. It's a shame, because it would have been perfect: a woman undergoes surgery to save her sight, leaving blind in the hospital for weeks. When eventually the gauze is removed and she is fitted with the special new glasses she'll need to see, she discovers that everyone in the hospital has an animal's head. Her doctor is a terrier, her nurse a cow. Like the greatest episodes of that show, the protagonist of "The Blue Lenses" endures a series of slow stages of increasing horror: first, she assumes it must be a tasteless practical joke. Once she can no longer deny the truth, the hammer falls: her fiance appears at her bedside with a vulture's head.

"The Blue Lenses" works so perfectly because it draws on a fear we have all experienced: the fear that, despite what they say, the people in our life do not care about us. The protagonist Marda and her fiance Jim have arranged for one of the hospital's nurses, Nurse Ansel, to spend a week at their home as a private caregiver during Marda's convalescence, but Nurse Ansel proves to have a snake's head. Without saying so explicitly--which, honestly, is one of the sharpest things about this story--Du Maurier insinuates to the reader that Jim and Ansel have conspired behind Marda's back to steal her money and run off together. Marda can turn nowhere to assuage this betrayal because the entire world is secretly a zoo; anyone on the street might be a vulture or a jackal looking to steal and kill. Marda sees once and for all what we all may have suspected, that the world is a hostile place and we are alone in it.

The title story excepted, the two strongest stories in this collection avoid the supernatural: In "The Alibi," a man decides to choose a house at random and murder whoever answers the door. He pretends to be an artist looking for a spare room, and takes the alibi so far--buying canvases and paints--that he actually does become invested in the art he is making, only to find himself accused of the murder he'd forgotten to commit when the tenant kills herself. In "Ganymede," a classical scholar falls for a 15-year old waiter in Venice, sublimating his pedophilia, transforming it into a fantasy that the young boy is the title cupbearer to Zeus. The boy's uncle sees his desire and insinuates himself into the man's life--with deadly results!

It's hard not to ruin those stories because they rely on third-act twists, both of which imagine what happens when our darkest impulses are allowed to escape our control and set loose in the world. For Du Maurier these dark desires are both uncontrollable and self-defeating; we really can't help destroying ourselves.

The other stories in the collection are a mixed bag of genre experiments. Stories like "The Pool," about a girl who imagines (?) a utopian world inside a garden pool at her grandmother's, and "The Chamois," about a woman whose husband is obsessed with hunting a rare species of European mountain goat, seemed to rely more on atmosphere and vague insinuations than the sharp insights of Du Maurier's best work. "The Menace" is a pretty pointless tale about what might happen if you could record emotional intensity on film, and how an old actor's career might be threatened if he had to be rather than act.

The worst of these, though, is "The Archduchess," a story I found morally and politically dubious as well as narratively flat. "The Archduchess" tells the story of the country of Ronda, a tiny European principality run by a succession of Archdukes who control the secret of permanent youth. The Rondese are entirely satisfied until a pair of agitators--a factory owner and a newspaperman--stir up rebellious sentiment with their propaganda, provoking the Rondese to storm the palace gates and kill the Archduke. When Ronda is just another democracy among the democracies of Europe, its mystique is punctured and the Rondese become as disillusioned as the rest of the modern peoples of the world.

I would say I don't understand this story, but I'm afraid I do: it's a bit of anti-democratic agitprop as delusional as anything published by the evil newspaperman. Industry (fair enough) and the media (uh-oh) are the enemy and monarchy the ideal state. The grievance that the Archduke had been keeping the secret of permanent youth to himself (which is true!) is a manufactured one, and the Rondese open themselves to suffering when they are hoodwinked by ideas of egalitarianism. Does that sound like a shitty bit of royalist politics? Well, it's also very boring!

It's tempting to make a connection between "The Archduchess" and the title story: do the blue lenses show the truth about a world that is so hostile and dangerous only a benevolent monarch can keep order? Is Du Maurier's outlook, with its fear of human nature, essentially a conservative one? I don't really know anything about Du Maurier's politics outside of her fiction, but I think it's possible that the best horror fiction is essentially reactionary, and Du Maurier may fit neatly into that. Regardless, "The Blue Lenses" is one of her best, and it was a great Halloween read for me this year.

No comments:

Post a Comment