Ah, Lord Shardik: supreme, divine, sent by God out of fire and water: Lord Shardik of the Ledges! Thou who dist wake among the trepsis in the woods of Ortelga, to fall pray to the greed and evil in the heart of Man! Shardik the victor, the prisoner of Bekla, lord of bloody wounds: thou who didst cross the plain, who didst come alive from the Streel, Lord Shardik of forest and mountain, Shardik of the Telthearna! Hast thou, too, suffered unto death, like a child helpless in the hands of cruel men, and will death not come? Lord Shardik, save us! By thy fiery and putrescent wounds, by thy swimming of the deep river, by the drugged trance and savage victory, by thy long imprisonment and weary journey in vain, by thy misery, pain and loss and the bitterness of thy sacred death; save thy children, who fear and know thee not! By the fern and rock and river, by the beauty of the kynat and the wisdom of the Ledges, O hear us, defiled and lost, we who wasted thy life and call upon thee! Let us die, Lord Shardik, let us die with thee, only save thy children from this wicked man!

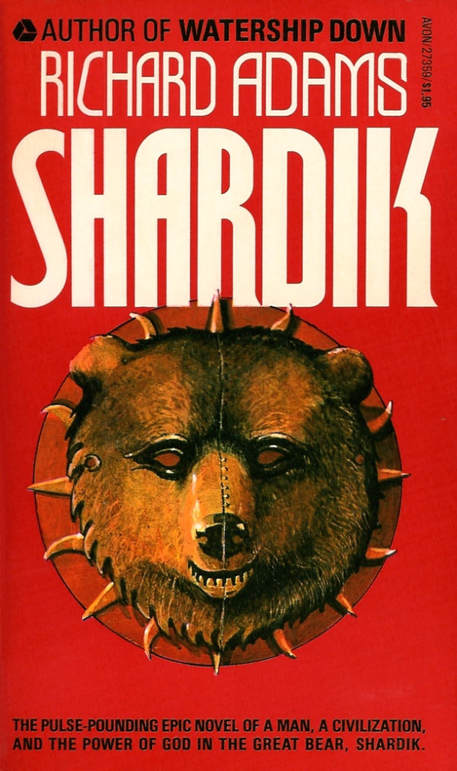

Kelderek is a lonely hunter, considered by the other Ortelgans to be something of a simpleton because of his habit of playing games with children. That all changes when a fire on the other side of the Telthearna, the great river in which Ortelga is an island, drives an enormous bear into the woods. The bear saves Kelderek's life from a marauding leopard, then disappears, but the priestesses on the outpost of Quiso are certain that what Kelderek has seen is the reappearance of Lord Shardik, the legendary bear who is the Power of God.

Honestly, I expected Shardik to be about bears the way that Watership Down, also by Richard Adams, is about rabbits. In Watership, Adams humanizes the rabbits, not by forcing them into human behavior but interpolating the behavior of rabbits into human frameworks of emotion and cognition. But the great bear, Lord Shardik, cannot be understood through human paradigms. Shardik is a bear, and he does what bears do; he is as likely to reach out a claw and maim or kill his worshippers as anyone else. Like Aslan from C. S. Lewis' Narnia novels, he is a representation of Christ, as well as other notions of the divine, but more convincing in that, like both God and wild animals, he remains outside human understanding.

What Shardik does have in common with Watership Down is the thoughtfulness and attention with which it constructs a fictional religion. In Watership, the rabbit's religion focuses on the legendary rabbit El-ahrairah, who is a trickster figure like you might find in traditional North American or African religions. Shardik, by contrast, is Abrahamic in his immense power and his moral imprimatur; the conflict of the novel, at least at first, is between those who believe they can use Shardik's power and those who believe they must follow the lead of Shardik. Kelderek, refusing the wisdom of the priestess known as the Tuginda, falls in with a nationalist baron named Ta-Kominion who believes that Shardik has come to free them from the imperial rule of the city of Bekla.

For a while, Ta-Kominion's beliefs are validated: Shardik helps the Ortelgans to rout the superior Beklan forces in battle, and Kelderek, as the priest of the bear, becomes the king of Bekla. (Adams smartly avoids all the Game of Thrones-style political machinations, jumping five years from the victory of Shardik over the Beklans to the height of Kelderek's power.) But Shardik wastes listlessly away in a cage in the Beklan palace, and Kelderek, we learn, has let the child slave trade prosper as an expedient to defeat the remaining Beklan rebels. It's as good an image as I've ever seen of the bankruptcy of religious nationalism, which uses and abuses the divine as a pretext for earthly power.

Eventually the rebels siege the palace and free Shardik, whom Kelderek follows into the vast wilderness. Following Shardik depletes him mentally, spiritually, and physically, and then he finds himself captured by one of the very slavers who has prospered under his rule. He comes face to face with the cruelty he has allowed, and it leads him to the point of death until Shardik returns to wreak a final judgment of divine wrath. In the end of the novel, the cult of Shardik has transformed into an ideology that believes children must be protected at all costs. Though the shape of the novel makes sense, I was less interested in this widescale transformation than in the specific journey of Kelderek, who must be broken in order to fully realize what it means to be a follower of Shardik. Whether this is a Christian allegory only, I'm not sure, but I do know that Kelderek's refrain, "I offer you my life, Lord Shardik," sounds a lot like "Whoever loses his life for my sake will save it."

I'm not a huge fantasy reader, but I think religion in fantasy novels often tends to be silly. Shardik is a fun novel, that ought to please readers who want adventure above all, or skillful world building. But I appreciated the seriousness and the thoughtfulness behind the book's ideas about religion, which, like El-Ahrairah in Watership Down, are both strange and familiar.

1 comment:

lol bear go rrrrrr

Post a Comment