Here I pause again, having taken you, reader, from town to town--from the little mining village of Saltus to the desolate stone town whose very name had long ago been lost among the whirling years. Saltus was for me the gateway to the world beyond the City Imperishable. So too, the stone town was a gateway, a gateway to the mountains I had glimpsed through its ruined arches. For a long way thereafter, I was to journey among their gorges and fastnesses, their blind eyes and brooding faces.

Here I pause. If you wish to walk no farther with me, reader, I do not blame you. It is no easy road.

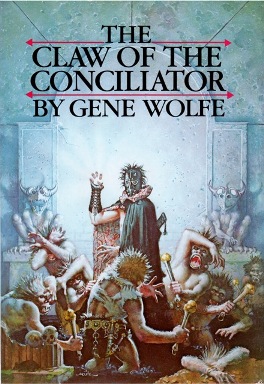

The Claw of the Conciliator is the second book in Gene Wolfe's Book of the New Sun tetralogy, following the torturer Severian as he continues his journey away from the Citadel of his upbringing toward--well, what exactly? At one point he tells us of his various missions, each of which seems to be of vital importance, but which strain against each other not just for him, but the reader, making it difficult to read the book as a quest narrative like you expect: he wants to make his way to Thrax, the city where he's supposedly posted as a torturer after having been exiled from the Citadel; he wants to find and protect Dorcas, the waif-like girl who appeared in a lake; he wants to serve the rebel Vodalus, who fights the ruling Autarch; he wants to return the all-powerful healing crystal known as the Claw of the Conciliator to the religious order who guards it. Along the way, here are some of the things he encounters:

A cave full of aggressive glowing aps-people. An ancient giant who seeks to control Urth, and wants to seduce Severian to live at the bottom of the sea. Flying bat-like creatures made of night that burrow into your body for warmth, and that separate into two creatures when you cut them with your sword. A robot who's been grafted with flesh and organs. (Not, significantly, a person who's been grafted with robotics.) The House Absolute, seat of the Autarch, which turns out to be build entirely underground. The Second House, a--well--second house built in secret around the House Absolute, full of mysterious and hidden passageways. Hideous cacogens, disguised as human beings, but who really have thousands of eyes laid out like a pinecone. A secret ceremony in which he is invited to ingest the flesh of his dead love Thecla, after which her memories continue to live on him.

...And a lot of other stuff, besides. Looking at the list, you get the impression that The Book of the New Sun is a particularly inventive but also fairly formulaic fantasy series. But what makes Claw of the Conciliator, like The Shadow of the Torturer, so engaging is the sense I get that it's not really interested in being a fantasy or science fiction book at all, and that the whole thing is a kind of papier mache facade that's concealing another kind of book entirely, or perhaps nothing at all. More than once, Wolfe pauses the narrative to include another kind of genre entirely: first a book of legends, then a script for a play that Severian performs, which is so mind-boggling that it reminded me of nothing more than Faust.

Everything comes at you whip-fast, introducing new characters and ideas and then undoing or recontextualizing them in a way that makes the reader's footing supremely unsure. No sooner does Severian meet the rebel Vodalus in the woods and agree to carry a message to a spy in the House Absolute than the spy turns out to be the Autarch himself. Is the rebellion just a red herring? If so, what's the "real story" here? Is it about the giants that live in the sea who want to exert dominion on the land, or are they a red herring, too? Maybe every herring here is red.

Again, Wolfe suggests that the world of Urth may be a figment: in The Shadow of the Torturer, interlopers from our own time appear on a kind of safari. Here, Severian's friend Jonas suggests that he comes from a different place and time, and is perhaps thousands of years old. In a room of mirrors in the House Absolute he disappears--presumably, having known how to return to our own era, perhaps slipping through time, but perhaps because Urth itself is a fiction or a metafiction.

I feel like I haven't entirely captured just how strange these books are. Talking about them makes them seem ordinary, but they outstrip the capacity of my language to really capture, and that's part of what makes them so uneasy and unsettling. The quest continues, but it's almost like the book, and the very nature of its book-ness, is falling apart, and I have a hard time imagining these qualities intensifying for two more novels.

No comments:

Post a Comment