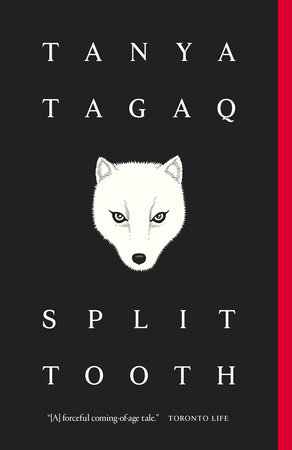

You want to talk about the frozen north? The Anishinaabe of Moon of the Crusted Snow have nothing on the Inuit as recounted in Tanya Tagaq's memoir-fantasy Split Tooth. You'd have to fly from Ontario across all of the frozen Hudson Bay, over mainland Nunavut, to reach Cambridge Bay, on the south tip of Victoria Island--a place on a similar latitude as Alaska's north coast--to compare the two. Tagaq, most famous as a traditional Inuit throat singer who won Canada's top music prize in 2014, recounts a coming of age in the remote tundra in vivid, specific detail, mixed with a healthy dose of magical realism and interstitial poetry.

The unnamed protagonist of Split Tooth isn't necessarily Tagaq herself, but when the narrative is in its realist mode, it offers the kind of specific detail that can only come from life as it's really lived in a place like Nunavut. She tells us, for instance, about carrying six lemmings around, one for each pocket of her coat--put two lemmings in a pocket and they'll start fighting, you know. She details the challenges of Inuit life with honest clarity--not the climate or the polar bears, mostly, but challenges like the crippling defeatedness of elders who try to keep the Inuktitut language alive after it's been beaten and shamed out of them. "We cut and paste words from our ancestry onto our paper-doll versions of ourselves," Taqag writes about Inuktitut class, "and everyone feels a little bit empty." In Cambridge Bay alcoholism is rampant, and worse addictions; the narrator is often found huffing gasoline. Sexual abuse is everywhere, and the narrator is both observer and victim. Split Tooth has all sorts of fantastical monsters, but none as frightening as the moment when the young narrator, hiding in the closet from her parents' boozy, violent parties, finds the door opening:

The door slides open, and my uncle sticks his head in. Towering over us, swaying and slurring. Blood pouring down his face from some wound above his hairline.

"I just wanted to tell you kids not to be scared."

Then he closed the door.

Later on in the novel, the narrator fellates a mystical humanoid fox. The novel's magical realist elements serve to both symbolize the idiosyncrasy of life in the north and to oppose its bleaker elements. Having grown into a young woman, the narrator lies out on the freezing ice and is impregnated by the Northern Lights. She gives birth to twins: a little girl who nourishes and gives life, and a boy who saps the life out of everyone around him, causing cancer and death. Are these symbolic of the twin mysteries and dangers of Inuit life? The twins are connected to the Inuit myth of Sedna, killed by her own father only to become a patron goddess of the Northern sea. Like Sedna's father, Tagaq's narrator must decide whether she can live with her children or whether she must sacrifice them, but it's clear that she cannot sacrifice one and save the other.

These sections mostly work, and provide an opportunity for flashes of really inspired writing. Less successful, I thought, were the interstitial poems, which almost always would have worked better if they had been integrated into the prose. I also really enjoyed the black-and-white illustrations by Love and Rockets comic author Jaime Hernandez, which somehow fit perfectly the starkness of the tundra, its nightless summers and sunless winters. In the end, Split Tooth offers what Moon of the Crusted Snow couldn't: an impression of real life among indigenous people in a very cold place, people who are as real, as frightening and inspiring, as the monsters and dreams that live there too.

No comments:

Post a Comment