I was at supper at his house, and he was not inclined to let me leave him at my usual time. 'If you go,' he said, 'there will be nothing for it but I must go to bed and dream of the chrysalis.' 'You might be worse off,' said I. 'I do not think it,' he said, and he shook himself like a man who is displeased with the connexion of his thoughts. 'I only meant,' said I, 'that a chrysalis is an innocent thing.' 'This one is not,' he said, 'and I do not care to think of it.'

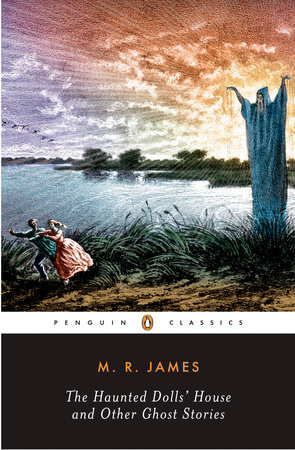

I read M. R. James' collection of ghost stories, Count Magnus, around last Halloween, and figured I might as well take this Halloween as an opportunity to read its companion collection, The Haunted Dolls' House. These stories have the same hallmarks as the first collection: they're set among stuffy British country houses and boarding schools; their ghosts and ghouls are linked to ancient and medieval objects and lithographs and old folderol like that; yet the ghosts and ghouls themselves are quite creepy. The monsters of The Haunted Dolls' House begin to bear a tedious similarity to the ones in Count Magnus--James has a thing for monsters made of nothing but hair--but still they are in effective contrast to the stories' gentility. James has a real knack for breaking through a fussy Victorian scene with the briefest glimpse of a horrible vision, like the friend above who admits, without any prior context, "I must go to bed and dream of the chrysalis." The chrysalis.

My favorites in this collection all center on the British countryside. The countryside, in British literature, is picturesque and historical, a setting for wanderers and tourists like Wordsworth. "A View from a Hill," plays on both of those expectations: it centers on a pair of binoculars, constructed by a mad experimenter using a dead man's eyes, that allows the viewer to see the particular towns--and the gallow's pole--as they were hundreds of years ago. Another, "A Warning to the Curious," repurposes an old legend about Anglo-Saxon crowns buried on England's eastern shore, which have kept the island safe from invasion, and which are guarded by a relentless spirit. The best story, "A Neighbour's Landmark," is no more inventive than a spirit who haunts a certain grove of trees, but the story's protagonist learns about it first as an aside in a historical pamphlet.

James knew that monsters are scariest when they're at arm's length, not just in space, but in time. Ghosts are the past come back to haunt us, as it haunts, in a manner of speaking, the classicist and the historian. The stories pile veil upon veil; every single one is in some way a story reported by a friend about a friend of theirs, or some other kind of multi-layered contrivance. There's a metaphor in there for the process of historical understanding, which passes through so many generations of understanding that you're never quite sure if you've got your eyes set on something real. In James, the horribleness of the beasts slices through these layers of interpretation, too awful to be legendary, and too ridiculous to be real.

No comments:

Post a Comment