Ancient fairy tales sooner or later become reality, liquor is mankind's greatest discovery. Without it there would be no Bible, there would be no Egyptian pyramids, there would be no Great Wall of China, no music, no fortresses, no scaling ladders to storm others' fortresses, no nuclear fission, no salmon in the Wusuli River, and no fish or bird migrations. A fetus in its mother's womb can detect the smell of liquor; the scaly skin of an alligator makes first-rate liquor pouches. Martial-arts novels have advanced the brewer's art. What was the source of Qu Yuan's lament? There was no liquor for him to drink.

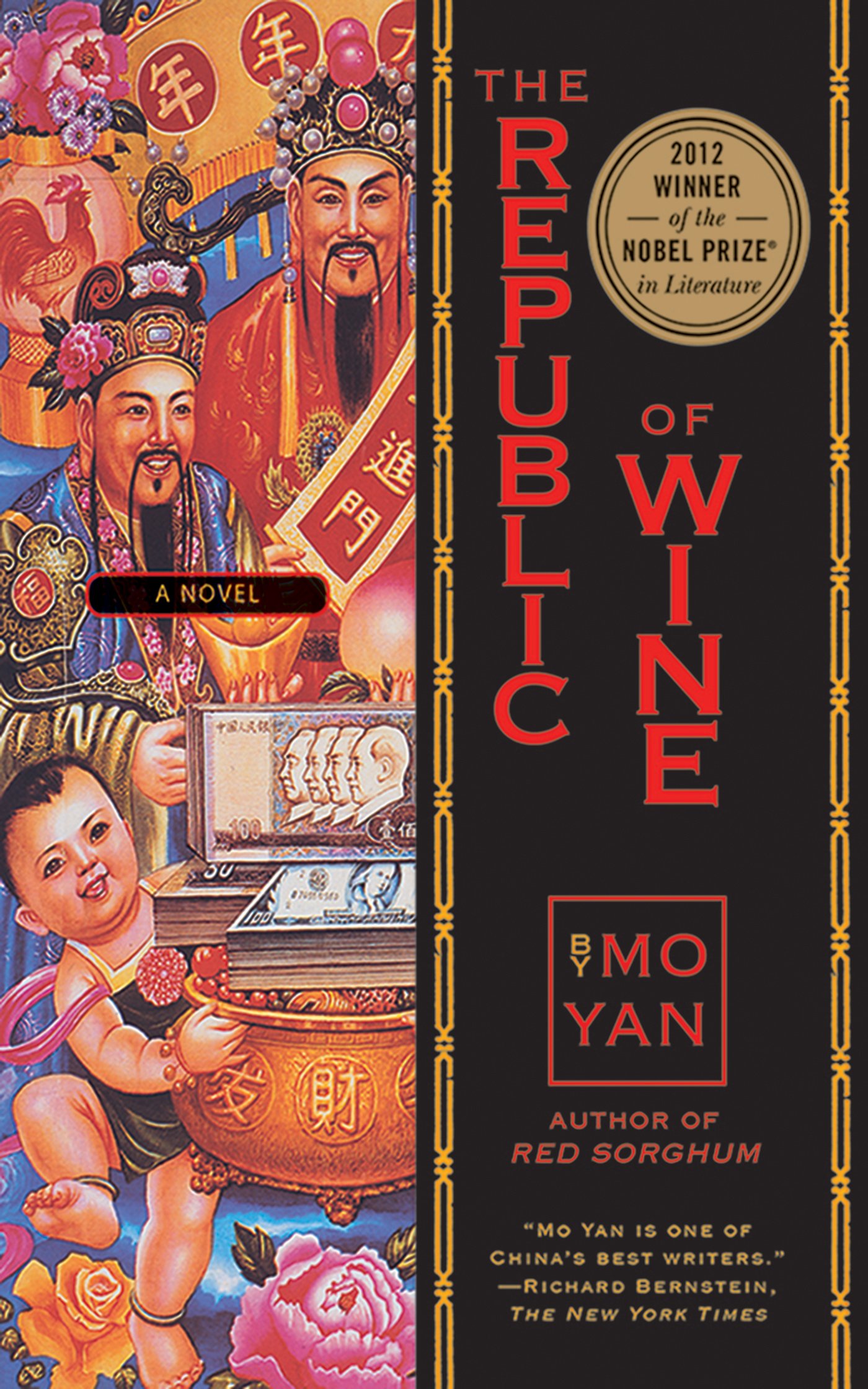

Investigator Ding Gou'er is dispatched to the city of Liquorland (rendered in the title as The Republic of Wine) to investigate a horrible crime: the administrators of the Luo Mine in that city have been accused of cooking and eating children. These "meat boys," as they're called, are part of Liquorland's famous tradition of gourmandizing: it produces the best, most exotic liquor and the best, most exotic food. Is the braised infant that is brought to Ding on a tray real, or is it merely a clever fake, made of lotus root, as the administrators claim?

The Republic of Wine is somehow weirder than that description suggests. There are apes that brew liquor in a secret mountain; there's a scaly child who wanders the streets seeking revenge against those who raise boys for their meat; there's an oily archvillain who can drink as much as he wants and never get drunk; there's a hideous dwarf who vows--and nearly makes good on his promise--to bed every attractive girl in the city. Oh, and there's this sentence: "He tripped over something, and discovered it was a string of frozen donkey vaginas."

Mo Yan won the Nobel Prize for works like this: often dreamlike, heavily biological, and pointedly satirical. At least, I assume it's satirical, though what exactly is being satirized is probably lost on me. I'm guessing it's about the luxurious tastes of the party classes in post-Mao China, and the way that decadence victimizes the powerless. But the nuances of the satire are lost on me, knowing as little as I do about China, and the clunky translation doesn't really help.

The novel is interspersed with letters between Mo himself and a young admirer and would-be writer, Li Yidou. Li lives in Liquorland, and his stories seem to provide Mo with a lot of the material he needs for The Republic of Wine; whether the stories are "true" seems to be a matter of not much consequence. Li's stories and Mo's novel begin to converge, and the detective story that the novel presents at first becomes much more complex and troubling. As both character and author get increasingly drunk, the semi-realist narrative is abandoned completely for an extended hallucination. The final pages are a stream-of-consciousness riff in the demarcation between Ding and Mo is blurred, and in which Mo admits, "Damn some will say I'm obviously imitating the style of Ulysses in this section Who cares I'm drunk..."

The Republic of Wine isn't an easy read. It's a little like reading the liner notes to a Captain Beefheart album. But it'll reward those for whom weirdness is its own virtue, and its scatological sensibilities are pretty in tune with Joyce. It made me want a drink.

No comments:

Post a Comment