Here's a partial list of the protagonists of the novels read by my freshman class this past year: Holden Caulfield. Winston Smith. John Singer. Pip. Huckleberry Finn. You may notice they have something in common: they're white, and they're male. With the exception of Mick Kelly, one member of the ensemble cast of The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, there are no female protagonists, and no protagonists of color. These facts aren't lost on the students, either.

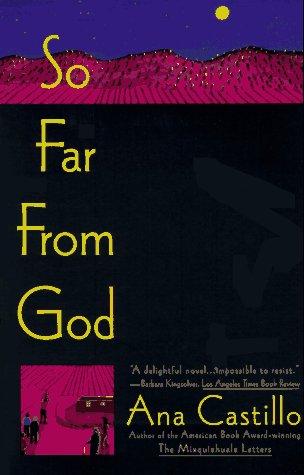

And yet, it's not an easy problem to solve. House on Mango Street? Persepolis? Already read in earlier grades. Song of Solomon? Their Eyes Were Watching God? Woman Warrior? The later grades. We tried to solve the problem by adding Kindred, but in my eyes that novel is simply not good enough. The sad truth is that canonical books with female protagonists of color--the kind that are unquestionably of literary value, as a matter of consensus--are so few that they already occupy places in the curriculum. I don't mean to say that there aren't hundreds of excellent books that would work well, only that save for a select few, they exist at the margins of literary prestige, needing to be discovered and championed. So Far From God, which I read at the suggestion of a fellow teacher, is one of a handful of books I read recently in search for a solution.

Unfortunately, I don't think this book is it--at least, not for me. So Far From God is the story of a Latino family living in New Mexico, Sofi and her four daughters: Esperanza, Fe, Caridad, and La Loca, a mysterious and antisocial child who seems to dwell in a separate, more spiritual world. The book opens with La Loca dying and then returning to life at her own funeral, then flying up to the roof of the church.

These magical realist touches recur throughout the book, drawing from a Spanish language tradition typified by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. It's not a style I love, honestly--though I ought to admit I've never actually read a book by Marquez. In Castillo's hands, at least, it seems to me that the magical bits undercut the realism and plausibility of the characters, eating away at the sympathy we might otherwise feel for them. When Caridad, famous in town for her licentious ways, is found brutally mangled by the side of the road, La Loca's prayer intervention restores her mysteriously to health--but at the expense of the emotional impact of Caridad's injuries. I don't mean that we feel less for Caridad because she is magically restored, but that she becomes less a human protagonist than a vehicle for a magical experience that the narrative is more interested in, despite its humanist and feminist pretenses. Similarly, the story ushers Esperanza off to the Middle East as a war correspondent, where she stays conveniently out of sight until her death, at which point she returns as a mystical presence to her family's New Mexico home--a more interesting presence, it seems, than the living Esperanza who has been absent from the story for a hundred pages.

In fact, the part I found most affecting was the death of Fe:

The rest of this story is hard tor elate.

Because after Fe died, she did not resurrect as La Loca did at age three. She also did not return ectoplasmically like her tenacious earth-bound sister Esperanza. Very shortly after that first prognosis, Fe just died. And when someone dies that plain dead, it is hard to talk about.

But "plain dead" is something that Castillo isn't able to talk about, beyond that paragraph above.

The book has a lot of strengths, and I would recommend it to interested students. It shuffles around a large cast without seeming frenetic or distracted. Castillo cultivates a unique voice, peppered with Spanish words and slang phrases that harmonize with the narrative. But I don't think I'll be teaching it in class.

No comments:

Post a Comment