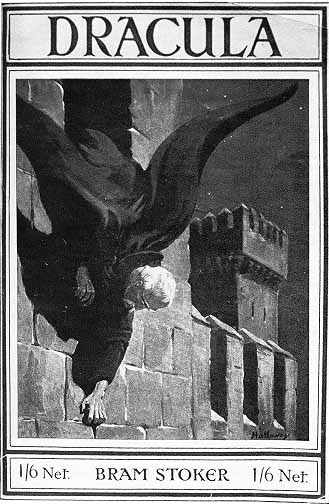

It is easy enough to give Bram Stoker credit for establishing the way we think about vampires. Really, Dracula is the vampire, the unquestionable model for every cheap costume and bad CW show today. But the early film adaptations, like F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu, have as much to do with that conception as Stoker's novel, and the Dracula of Dracula is at times unrecognizable. For every detail that Stoker popularized--a vampire's ability, for example, to turn into a bat, his lack of a reflection, or aversion to crucifixes and garlic--there's an aspect that has been forgotten, like Dracula's bestial hairiness, or his ability to climb down a wall like a lizard. Stoker's Dracula walks around freely during the day--but he doesn't do any sparkling of note.

The first part of Dracula is a lot of fun. Jonathan Harker, tasked with traveling to the Count's remote Transylvanian castle to oversee the sale of some English property, becomes the Count's prisoner. He is almost eaten by Dracula's sexually aggressive wives; he discovers the Count sleeping in a coffin filled with dirt; he escapes but with a fair amount of psychological trauma. The second part, in which Harker and a group of others, including his wife Mina and Dr. Abraham Van Helsing, try to prevent Dracula from setting down roots in England, is regrettably more tedious. The Count is mostly absent, save for one memorable scene in which he forces Mina to drink his own blood out of his chest wound (establishing a psychic connection between them, naturally). The plot is mostly concerned with locating and destroying the boxes of Translyvanian earth the Count has brought with him, and where he must sleep.

There's a wearying earnestness to these chapters--which really pound in the goodness and sacrifice of the cadre of heroes--that belies the essential weirdness of the Dracula figure. Dracula works best when the weirdness punctuates the stodgy heroism, like the half-mad foreign-y ramblings of Dr. Helsing, or scenes with totally mad Renfield, who helps to fulfill Dracula's nefarious schemes from inside a mental asylum, and eats a lot of bugs.

One thing I didn't expect from Dracula was its extreme conservativeness. As a story of an Eastern European ruler trying to set up shop in England, it's a parable of the threat of foreign invasion. (It's never clear to me why Dracula, who has difficulty passing over running water, would even want to travel to England instead of merely feasting on the blood of continental Europe.) Vampirism becomes a stand-in both for the terrors of homosexuality and female sexuality. Here's how the darling, chaste Lucy Westenra is described when she becomes the Undead:

My own heart grew cold as ice, and I could hear the gasp of Arthur, as we recognized the features of Lucy Westenra. Lucy Westenra, but yet how changed. The sweetness was turned to adamantine, heartless cruelty, and the purity to voluptuous wantonness. Van Helsing stepped out, and, obedient to his gesture, we all advanced too; the four of us ranged in a line before the door of the tomb. Van Helsing raised his lantern and drew the slide; by the concentrated light that fell on Lucy's face we could see that the lips were crimson with fresh blood, and that the stream had trickled over her chin and stained the purity of her lawn death-robe.

In that short passage, Stoker uses the word "purity" twice to describe Lucy's former state, and emphasizes with the white robe which is daubed with blood--I don't think I'm reading too much into it to see in this description a loss of virginity, especially with her "voluptuous wantonness." To make matters worse, Lucy's taken to preying on young children.

Much of the novel's tedious second half is concerned with protecting Mina, who is Dracula's next chosen victim (he works on one person at a time, apparently, not converting them until all of their blood is drained), and whose "purity" is threatened in turn. Mina, of course, has no place in the heroes' schemes besides that of a talisman to be protected, and the final scene in which Dracula is defeated is described in her diary as she watches from hundreds of feet away.

Besides relegating its principal female character to the sidelines, this is a peculiar and anti-climactic way to end the novel. We've been wanting to see Dracula again for a hundred pages or so, and the final "battle"--such as it is--is described at a safe remove which lacks intimacy and immediacy. It's typical of Dracula, which I liked quite a bit, but wanted to like a lot more.

2 comments:

It's been years since I read Dracula, so my memory lacks immediacy, but I remember being struck by how much Dracula exists in every other vampire story (Twilight and Interview with the Vampire were both in my mind when I read it), but I think that a lot of vampire lovers shy away from it for some reason.

I really enjoyed the multi-genre of the text, and was impressed that it had those features that many people consider to be modern quirks (like the way A Visit From the Goon Squad does it).

IIRC, epistolary novels were sort of faddish in the 19th Century. Jane Austen wrote one.

Post a Comment