And though I feel I have achieved my fullest incarnation here as a professional, writing a book with reams of endnotes, I also feel a kinship with the amateur that I can only call queer. I know, I know: I have been professionally trained as a medievalist, have taught full time for more than thirty years, and have been recognized and well rewarded. So why should I ever feel myself to be an amateur in a world of professionals, ever lacking, ever behind? Because I am a queer--a dyke and only sort of white. Because I am a medievalist, and studying the Middle Ages is, finally, about desire--for another time, for meaning, for life--and desire, moreover, is so particularly marked for queers with lack and shame. These feelings are not simply personal insecurities. Like my queerness, my feelings of amateurism aren't a stage of development, aren't ever going to go away; as in the case of queerness, too, my goal is to contribute to the creation of conditions in which an amateur sensibility might be nurtured and its productivity explored.

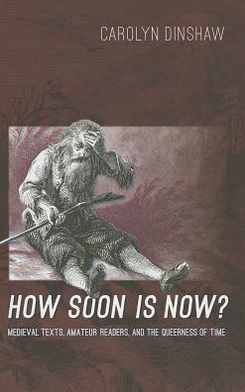

Amateurism is at the heart of Carolyn Dinshaw's How Soon is Now?, but it is the kind of book only a well-regarded professional could have published: part academic work, part personal essay, compelling but a little off-balance, with chapter titles taken from the discography of The Smiths. On its face it is a book about the Middle Ages, but often it's a book about books about the Middle Ages, and the cover illustration depicts Washington Irving's Rip van Winkle.

There is a queer way of experiencing time, Dinshaw argues, unregulated by the ticking-clock urgency of marriage and procreation. She describes queer time in a number of medieval texts in which "straight" subjects find their time disjointed, displaced, or transformed. The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, for example, abscond to a cave to escape Roman persecution of Christians only to wake up hundreds of years later in the Christian Empire.

There is something about medieval texts, Dinshaw contends, that makes them ripe for stories of queer time, especially as an attraction for amateur medievalists who, through their non-professional (and thus, in a way, queer) passion for the time period, are out of joint with their own era. Geoffrey Crayon, the narrator of Washington Irving's collection which contains the Rip van Winkle story is one of these, and as such is linked to Rip as a man out of time.

For each chapter, Dinshaw ends with a personal narrative connecting her own life experiences--her queerness and amateurism--to the observations she is making about medieval texts. I like the way that How Soon is Now? puts its subject matter into practice; skipping merrily across centuries and between the amateur and the professional spheres. But in the end, it seems somehow simultaneously overstuffed and half-finished, as the different threads that Dinshaw follows--time, queerness, amateurism, the Middle Ages--are never tied together in a satisfactory way. Perhaps that's a heteronormative thing for me to say.

2 comments:

This really makes me feel like almost anyone can publish almost anything if you pull Academic Term from Cup A and Hot Identity from Cup B and then work it together in a book.

As an academic, do you think that this book offers anything necessary or interesting or important to lit crit?

I actually liked the book. I didn't mean to come off as if I didn't. I did think it was a bunch of parts looking for a whole.

Post a Comment