I read Jeanette Winterson's Sexing the Cherry for class a few years back, and really loathed it. It probably remains, to this day, the least enjoyable book I have read since the Fifty Books Project began. I'm not going to link to it because it's a pretty thoughtless review, and I don't do a very good job of laying out what I disliked about it. But, if I recall correctly, I was bothered by the way the skeleton narrative was padded out with digressive passages of parable and fantasy that failed to illuminate anything about the main plot, thin though it was. Sexing the Cherry struck me as a book of vignettes hastily cobbled together in the hopes that their multiplicity would mask their rather shallow observations about gender and sexuality.

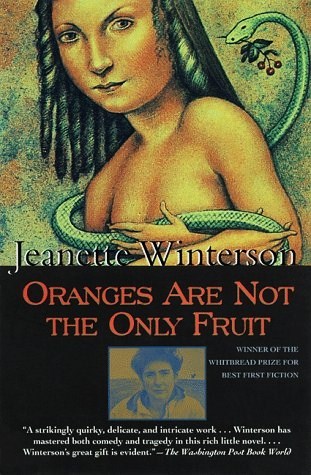

You can imagine what I was thinking when I found out that Winterson's debut novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, had been made a mandatory text for one of the classes I'm teaching next year. I picked it up with trepidation, to be sure--but, I am happy to say, I found Oranges to be a much better experience. Perhaps some of that is because of ways I have changed in the past seven years. But only some.

Unlike Sexing the Cherry, which has the intimacy and depth of a collection of fairy tales, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit presents itself as semi-autobiographical, detailing Winterson's childhood in an extremely evangelical family and the conflict created by her attraction to women. Winterson's mother is kooky, an obsessive who throws herself into evangelizing with abandon, but Winterson's own belief is presented as very real and very treasured. The scene in which Jeanette and her young lover, Melanie, are exposed in front of the church, is tragic and real:

'I will read you the words of St Paul,' announced the pastor, and he did, and many more words besides about unnatural passions and the mark of the demon.

'To the pure all things are pure,' I yelled at him. 'It's you not us.'

He turned to Melanie.

'Do you promise to give up this sin and beg the Lord to forgive you?'

'Yes.' She was trembling uncontrollably. I hardly heard what she said.

'Then go into the vestry with Mrs White and the elders will come and pray for you. It's not too late for those who truly repent.'

He turned to me.

'I love her.'

'Then you do not love the Lord.'

'Yes, I love both of them.'

'You cannot.'

It's not always so heavy; in fact, Winterson treats her story with just the right amount of irony and humor (which, if I recall correctly, were noticeably absent from Sexing the Cherry.) There's a scene--Lord knows how much truth is in it--where Jeanette, exiled from her family because of her sexuality, has taken a job driving an ice cream truck. Through an odd turn of events, she's forced to help cater a funeral for an older woman who she had been very close to, and where she must encounter her mother and her mother's friends. Afterward, the guests line up for ice cream before she can get away, and her mother's crew huffs over Jeanette "making money off the dead"--which is a great image of the way the judgment of others has of twisting one's identity. But it's the absurdity of the scene that sells it, that somehow works to balance the awful sadness of it.

Winterson devotes a large section of the last chapters to a fable about a princess named Winnet. This story reaffirmed my feelings about Sexing the Cherry, which was basically a collection of similar fables. I would not claim that the story of Winnet has nothing to say about Jeanette's experience--surely, there are many parallels that Winterson wants us to see. But the whole thing is so unnecessary, a needless diversion in a novel that would work much better without it.

3 comments:

Wow! What grade/class is reading that? That seems verrry progressive reading! (and by progressive I mean filled with liberal propaganda)

I read this in one sitting years ago. In the GLBT Life class I co-taught at NCSU, I was really tempted to use Winterson's novel Written on the Body as a vehicle to talk about gender identity as a social construct, but I ended up not using any fiction. I haven't read Sexing the Cherry, but I do agree with what you had to say about Winnet.

It's either ninth or tenth grade. I forget which.

Post a Comment