Flashlight and camera skitter across ceiling and floor in loose harmony, stabbing into small rooms, alcoves, or spaces reminiscent of closets, though no shirts hang there. Still, no matter how far Navidson proceeds down this particular passageway, his light never comes close to touching the punctuation point promised by the converging perspective lines, sliding on and on and on, spawning one space after another, a constant stream of corners and walls, all of them unreadable and perfectly smooth.

Flashlight and camera skitter across ceiling and floor in loose harmony, stabbing into small rooms, alcoves, or spaces reminiscent of closets, though no shirts hang there. Still, no matter how far Navidson proceeds down this particular passageway, his light never comes close to touching the punctuation point promised by the converging perspective lines, sliding on and on and on, spawning one space after another, a constant stream of corners and walls, all of them unreadable and perfectly smooth.Finally Navidson stops in front of an entrance much larger than the rest. It arcs high above his head and yawns into an undisturbed blackness. His flashlight finds the floor but no walls and, for the first time, no ceiling.

Only now do we begin to see how big Navidson's house really is.

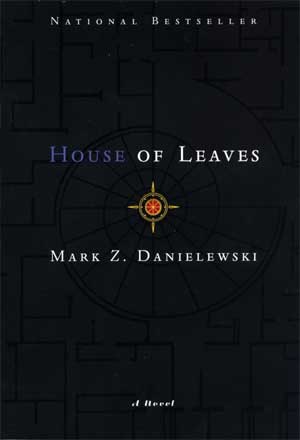

Here is my attempt at explaining what happens in House of Leaves, moving from the outermost onion-skin of reality to the innermost:

1.) A down-and-out pleb named Johnny Truant who works at a tattoo parlor is invited by his friend Lude to the apartment of an old blind man named Zampano who has recently died. Johnny finds in Zampano's apartment a tattered, deranged-looking manuscript for

2.) House of Leaves, an academic study that Zampano has been writing about

3.) The Navidson Record, a fictional (even within the framework of Johnny Truant's reality) documentary film about a famous photographer named Will Navidson who buys a new house with his family in Virginia. The events of this film form the core of Danielewski's novel: While doing some idle measurements, Navidson discovers that his house is three quarters of an inch longer on the inside than the outside. After a couple weeks of inviting people over to investigate this strange issue, one morning Navidson and his wife wake up to find a door that wasn't there before.

This door leads, not to the outside of the house as it should, but into a dark phantom hallway. What the fuck. Investigating against the wishes of his wife, Navidson discovers that this hallway leads into a large room, which in turn leads into a larger room--so large he cannot explore it by flashlight. Further explorations reveal further spaces, each larger, and each inconstant--spaces shrink and grow, doors move, etc. Eventually Navidson hires a team of explorers to investigate, but their journey--which takes over a week--causes them to approach madness. There is a truly terrifying scene in which Navidson is at the bottom of a long spiral staircase--which took the exploration team days to descend, but which has taken Navidson only hours--and by radio he instructs his friend at the top of the stairs to drop quarters down the shaft to see how long they take to fall. Suddenly the staircase begins to stretch, and Navidson is abandoned at the bottom. Fifty minutes later the quarter finally hits--which, according to the math, suggests a depth greater than the circumference of the earth at the equator.

In the meanwhile, we get two sets of footnotes: one is Truant interjecting his story as he compiles the manuscript into a typed copy; it recounts his slow descent into fear and madness as Zampano's book begins to take a toll on him psychologically. The others are meticulously compiled academic footnotes. Many are references to fictional books, but some border on the absurd: for instance, during a chapter in which Zampano discusses photography, there is a footnote that says, "also see," and then lists hundreds upon hundreds of photographers--probably every photographer you've ever heard of and eight hundred more. On top of this, Danielewski plays liberally with the format of the book, making great use of oddly oriented text, large black and white spaces, color coding, and concrete prose.

What's the deal, here? Steven Poole has called House of Leaves "a satire of academic criticism," which seems accurate. The ridiculous footnoting is compounded by long discursive and digressive passages on the nature of things like photography and the concept of echo, or the story of Jacob and Esau or the Minotaur. These discourses usually go nowhere and end up coming off as unfailingly dry.

But at the heart of House of Leaves is a genuinely terrifying tale. The story of Navidson, lost in the strange, mythical labyrinth of his own house is as psychologically terrifying as anything I can think of in horror films. The academic criticism bits tend to suck the air out of the entire narrative, overanalyzing everything but illuminating very little. Of course, to that you might say, "Well, that is the point--House of Leaves satirizes academic criticism by showing its power to crush art and make it impotent." If that is the case, it often does quite well, but is this a worthwhile goal? Is a book that pokes fun at academic criticism as worthwhile as a book that is truly horrifying, as the Navidson sections of this book are? Would it have been stronger without Zampano's overly analytical musings?

And then, of course, there's Johnny's story. Zampano's book seems to take a real physical and psychological toll on Johnny, who begins to feel as if he is being shadowed by a horrible monster. If Zampano's book is meant to show the way in which criticism destroys art, what are we to make of the way it still has such a palpable effect on Johnny--or, for that matter, the way that it has an effect on us when Zampano is removed from the immediate picture?

Ultimately, House of Leaves is a book that delights in leaving more questions than answers, a puzzle instead of a solution. I think that Danielewski would be pleased that I was having trouble pinning the book down, because it is a book that purposefully avoids being pinned down, and in that case it's quite successful.

4 comments:

I have perused this book many times at the bookstore. I am a bit of a peruser.

Still gathering your thoughts about HP7?

Everyone I know who's read the book hated Johnny Truant. What did you think?

I thought Johnny's story was good, but it wasn't nearly as compelling as Navidson's, nor did it interrupt the flow like Zampano's academicism.

I read a review that called Johnny "one narrator too many." That may be true, but there was a lot I liked about his narrative--I just wish it were as interesting as the narrative at the heart of this book.

Carlton: I am writing a very, very long review of HP7 that I will probably split into several parts. Look for it hte next few days.

Booyah!

Post a Comment